Arpita Shah Journeys Through the History of the Women in Her Family

Nalini by 35 year-old Indian, Edinburgh-based photographer Arpita Shah is a long-term project shot across India, Kenya and the UK. “It focuses on my maternal lineage and explores migration, memory and loss” Arpita says. “The series centers on my mother, my grandmother and myself and explores the intimacy, distance and tensions between generations of India-born women that have all grown up and lived across various continents and cultures.”

“Nalini is my grandmother’s name, so the story begins with her and was inspired by her. She was born in India but spent most of her childhood in Kenya, before moving back to India in her teens. Although I visit her in India every couple of years, I realized how little I really knew about what she was like as a young woman, her memories and experiences, and what her relationships were like with her own mother and daughter. Each year she gets more frail, forgetful and distant—I started this project to learn more about her and my female ancestors, because I wanted to feel closer to them and to document my family’s stories before they got lost. The series combines portraits of my mother and grandmother, with still lifes of sacred objects and family archives, which have travelled through space and time and been passed down through generations. As part of the series, I also photographed certain flora, interiors and landscapes that hold special significance for the women of my family.”

As a photographer, Arpita has always been really interested in notions of home and belonging: “This stems from my own experience growing up across India, Ireland and Saudi Arabia before settling in the U.K. I often explore these themes through the subject of the family, particularly focusing on intergenerational relationships between mothers and daughters. The family archive is also something I often draw from in my work, so in one sense Nalini felt like a very organic direction for me to go in. However, thinking back at when I consciously decided to start the project, a few years ago I had just arrived to India with my mother, and my grandmother Nalini was in a coma. We went to visit her in hospital and it was incredibly heart-breaking. I felt this very heavy sadness, deep longing and regret. She was in a coma for almost three weeks, and when she finally woke I asked her if she remembered anything and if she could hear me talking to her, and she said: “No, I dreamt I was floating in the sea between Africa and India.” I think that’s when I knew I wanted to and needed to make work about her.”

Working on Nalini was important for Arpita on a personal level. “It was only until the age of three that I lived in India with my mother, auntie, and grandmother before moving away with my mother and brother to join my father in the UK. Since then I’ve never had that tight maternal unit of Indian women in my life again. Although my mom and I visit our extended family in India every couple of years, sometimes it feels like too much time has passed, and other times it always feels too rushed. This project really allowed me to slow down and spend more time with my female family members, especially my grandmother and to listen, respond and interpret their stories through the lens with the landscapes, objects and family archives we were all connected too. I wanted to piece all of us together combining the past and present.”

“This project has also brought me closer to my grandmother and gave me a better understanding of my own mother’s relationship with her. I love my grandmother immensely but I can’t communicate with her because my Gujurati is very limited, so when I was making Nalini, her and I would spend hours together, sometimes trying to understand each other and other times in silence, with me observing her. For me this silence and the process of slowly photographing her has been so much more meaningful than language has been for us. This project created an intimacy between us which I’d never felt before.”

Nalini mixes portraits, still lifes, landscape photos and photos of interiors. “A lot of my previous work is more traditional, portraiture-based and more controlled, but with Nalini I took a very different approach. Whenever I traveled to India I would shoot 10-20 rolls of film and had nowhere to process it, so I wasn’t able to reflect on what was shot and respond to it, which is what I usually do. This made the project and process a lot more intuitive and slower: I had to trust myself but also challenge myself to be more creative. Also, at the start of the project my grandmother was in and out of hospital; sometimes I would go visit her for a portrait session and she wouldn’t be there, so instead I’d slowly observe her bedroom, home, plants and objects, and try to make a portrait of her without her being physically present.”

“Tactility was also really important in the work, I really wanted the images to evoke certain memories, emotions and experiences of the women in my family—capturing particular textures, tones and light was really essential. In most of the portraits I decided to only reveal fragments of the women: I wanted viewers to feel that same longing and desire for the past that I have, that urge to want to reach into an image and turn it around but not being able to.”

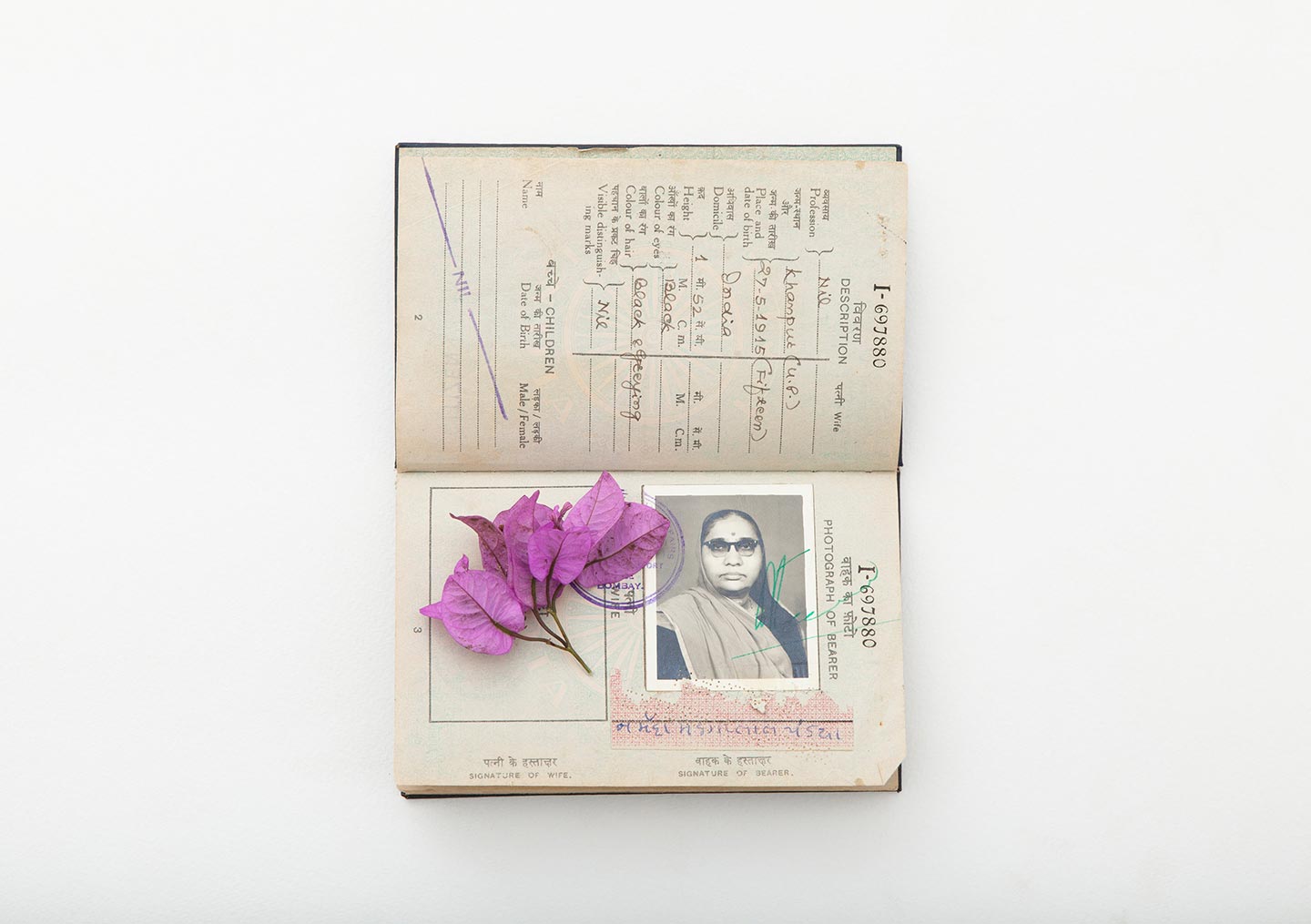

“Alongside the portraits, I also started collecting archival photographs and objects from attics of great uncles and aunts. These objects and photographs had traveled across continents through time and generations, as artifacts of my family’s journey. I wanted to include them in the series because they bare little scratches, scars and creases; like the body they have aged with time, full of stories and secrets. Sometimes I’d photograph these on their own in a clinical manner, as if searching for clues; other times they’d be decorated like a shrine with fresh sand or flowers that I collected from symbolic places I visited.”

One of the references Arpita had in mind while working on Nalini was this quote by Virgina Woolf: ‘For we think back through our mothers if we are women‘. “I thought a lot about these words and about the complex relationships women have with their mothers and how this changes as we get older, and how it changes again if one day we decide to become mothers ourselves. I was also very inspired by photographer Colin Gray’s book In Sickness and in Health and Miyako Ishiuchi’s Mother’s series. There is also this portrait of Nettie Harris being embraced by a power blue frock by Donigan Cummings that I’ve always loved. The tones in Nalini were very much inspired my grandmother’s lilac bedroom, and the fact that purple is her favorite color. I also used a lot of pastel blues to evoke the ocean, and also because my great grandmother only ever wore blue sarees. And the different shades of rose colors in the series are very much drawn from my memories of my mother and flora when growing up in India and Saudi Arabia.”

Although Nalini is a very personal project, Arpita feels that “there are some very universal themes in the project, especially that desire we all have to preserve our family history before it gets lost and that deep longing we have to maintain particular cultural traditions of our ancestors if our families are displaced across lands. I hope viewers will feel inspired to start documenting and archiving their family histories, sitting with their grandparents and taking notes, images and audio recordings (if they haven’t already started to do so).”

Arpita suspects the earliest influence on her photography was her father: “He was an amateur photographer and he photographed my mother a lot during my childhood. He’d often photograph her reflection in the mirror, and her dressed in brightly colored sarees standing next to trees and flowers in all the different places we lived in. I think this really influenced me and the images I make of her. In terms of photographers, when I was studying photography (many moons ago!) it was artists like Dayanita Singh, Thomas Struth, Emmet Gowin, Hannah Starkey, Zharina Bhimji, Maud Sulter, Hellen Van Meene, Jeff Wall, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Diane Arbus, Juliet Margaret Cameron and Richard Avedon. Visually, my photographs draw a lot from painters like John William Waterhouse, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Alan Ramsey, Raja Ravi Varma, William Merritt Chase and William Strang. I also study Indian miniatures and Mughal era paintings that depict women in flora.” Some of her favorite contemporary photographers are Hannah Starkey, Esther Teichmann, Rania Matar, Miyako Ishiuchi, Trine Søndergaard, Sophie Calle, Siân Davey and Dana Lixenberg (“and many more!“). The last photobook she bought was Pictures From Home by Larry Sultan; the next she’d like to buy is Dive Dark, Dream Slow by Melissa Catanese.

Arpita’s three words for photography are:

Myth. Memory. Obsession.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2024