Midwest Sentimental — Nathaniel Grann Explores the Idea of Family Thorugh Images of His Own One

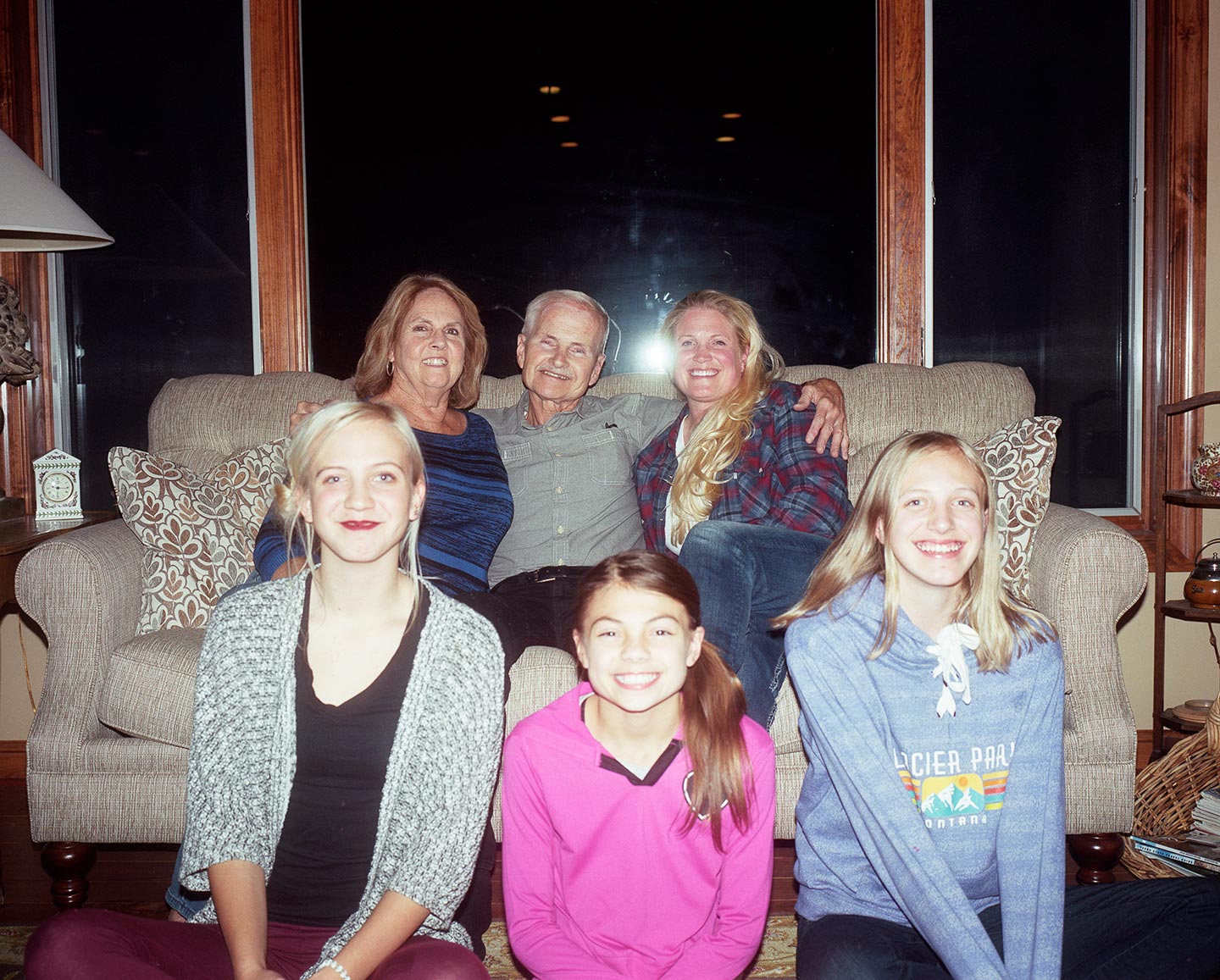

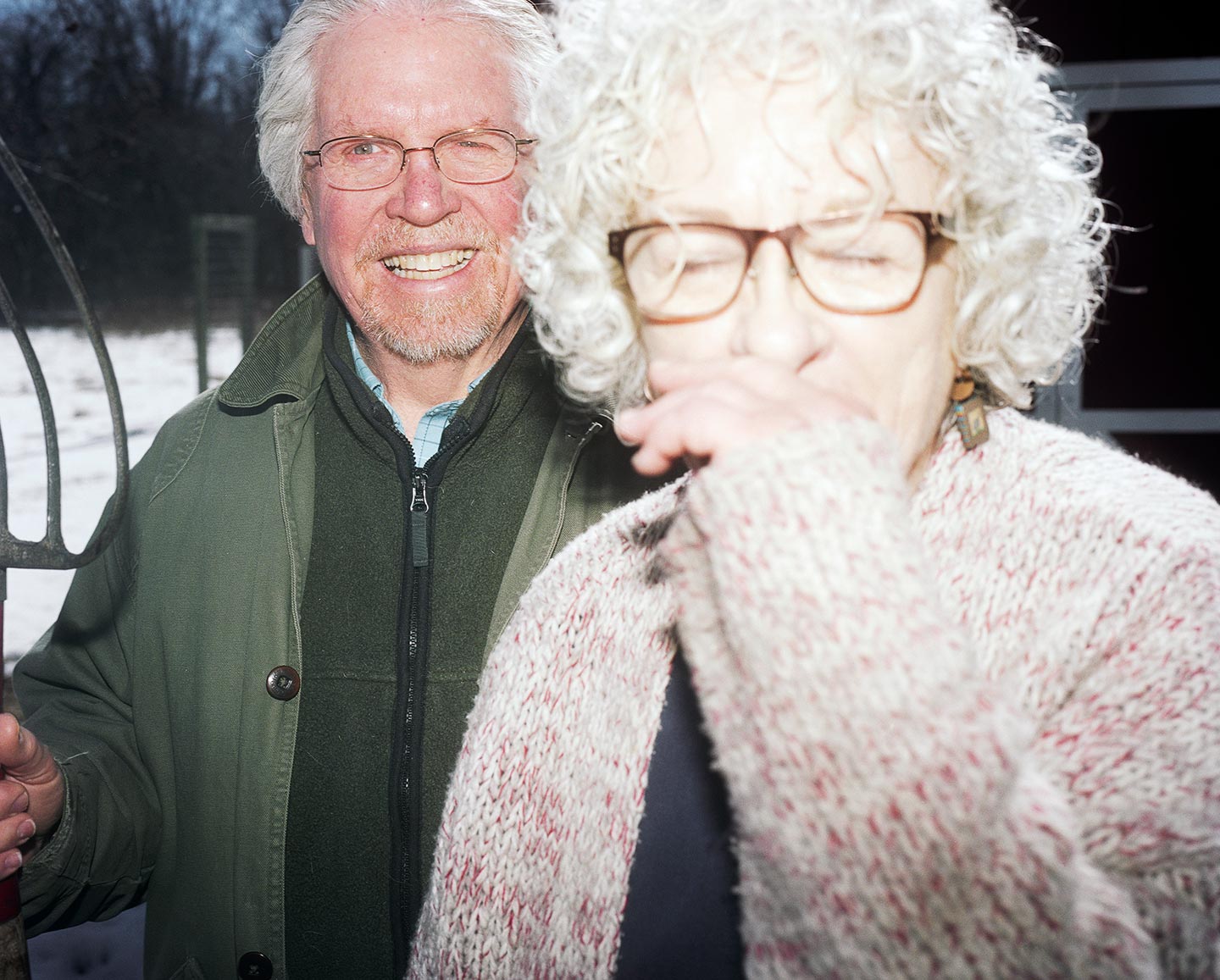

Nathaniel Grann, a 28 year-old American photographer, started working on his long-term project Midwest Sentimental (now available as a photobook—buy your copy) a few years ago, when he moved back to his hometown in the American Midwest to live with his mother and stepfather: “I started to experiment with different approaches to photographing my family and myself. As I was making the photographs, I was also thinking about things like: What makes a family click? What holds a family together? And what allows for a family to move on from a troubled past? Love, sadness, and humor came to define that period of time for me. In the three years I lived at home, I found few definitive answers; instead, what came of it was the experience of a collective exhale of momentary release and reflection.”

“My family’s story is a pretty standard American middle-class tale,” Nathaniel recounts. “My parents were high school sweethearts; they eventually married and had their first child (my older brother). Sixteen years later, I was born and a couple years after that, they divorced. As divorces go, it wasn’t the cleanest or the messiest, but ultimately, it was for the greater good of all parties involved. Now, both of my parents have remarried and it’s hard to think of my life without their respective partners in it.”

He started taking pictures of his family during his first year of grad school: “The projects I did at that time just kept going in circles and—the worst sin of them all—they just weren’t that interesting. I eventually began to use my family as models to test out new ideas. Those test photographs routinely ended up being more interesting than the ‘real’ versions I’d go out and make afterwards, and seemed to really resonate most with the emotional state I was in at the time. Luckily, most of my family was receptive to being photographed and the project grew from there.”

Nathaniel’s family members contributed to the project in ways other than modeling: “I had weekly conversations with them where would talk about shared memories, or I’d share the photographs I had been taking, or things that had been inspiring me. We’d chat about what we saw in those photographs and anything that they may have reminded us of. From there, I’d make a short list of new ideas for us to attempt over the coming weeks and reflect on what we had discussed.” While working on Midwest Sentimental, Nathaniel categorized the photographs into four different types: “Staged portraits, domestic scenes, self-portraits, and snapshots. Each approach was rooted in those conversations we had about creating images based on our shared memories and their reactions to how other photographers have tackled the domestic setting. If something provoked a direct reaction, we would set out at once to recreate or enact that image. Results varied as interests would change to another image in the middle of things, or the northern Minnesota landscape did not provide the right setting for an “actual” reproduction, often leading to images that had little to do with what they had originally been rooted in. While editing, emotional tones and responses were of more interest to me and how I would gauge the success of an image over the technical and aesthetic qualities.”

Midwest Sentimental is not a literal documentation of Nathaniel’s family: “The images should be viewed as a reflection of myself, as I play the role of something similar to a memorist. I’d hope that viewers can take away a sense of familiarity and some reflection on their own ideas on the notion of family. Family is complicated and full of nuances that are very particular to us as individuals, but ultimately, there are universal strings that run through all of our collective experiences. At the end of the day, this project is intensely personal to me; however, I’m not trying to present this work as documentation, but rather as an exploration of the ideas of family that I’ve been playing with in the past few years.”

“Photographers Larry Sultan and Doug DuBois paved a lot of the road for a project like mine,” Nathaniel says about his photographic references for Midwest Sentimental. “Both have created—in my mind—some of the most heartfelt bodies of work around the idea of family, and continue to be the caliber and quality of work to which I aspire. Mary Frey is another photographer who I feel has done so much in the genre of family and helped root my own understanding of what it means for a photograph to be ‘true.’ Her photobook Reading Raymond Carver is one I continually recommend and has been one of my favorites for some time.”

Nathaniel’s main interests as a photographer “have a changed a fair amount over the years, but they have routinely been rooted in an attempt to understand how photographs work: why do we react in certain ways to a photograph? What can a photograph tell? What does a photograph show?” His inspirations include “other photographers, musicians, writers, and/or painters. The short stories of Joy Williams have been on my mind a lot lately and I’m currently reading way too many Mike Mignola comics, so who knows what that could all lead to.” Some of his favorite contemporary photographers are Alec Soth, Lars Tunbjörk, Pao Houa Her, John Edmonds, Veronica Melendez and Ward Long. The last photobook he bought was 2017–2018 Gazetteer by Ethan Aaro Jones (“It’s not really photobook and not quite a zine, but I have really enjoyed this little map Jones has created of the American Midwest“).

Nathaniel’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Love. Resist. Refute.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025