Zora J Murff Explores the Effects of Redlining on Omaha’s Black Communities

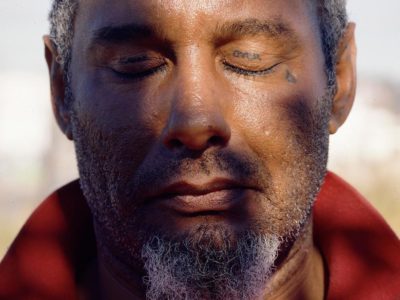

LOST, Omaha by 31 year-old American photographer Zora J Murff is a book published by Kris Graves Projects (buy your copy) included in a series of photobooks focusing on the landscape across the globe, as seen by a group of selected contemporary photographers. Zora shot the images in a community area of Omaha, Nebraska. “The series focuses on the history of the North Omaha neighborhood and how its landscape was shaped by racial dynamics, first through segregation and then—once segregation was made illegal—a continuation of that oppression by the government” Zora says. “This was done through a process called redlining: laws that restricted black individuals from receiving home loans, and discouraging white individuals with wealth from investing in those communities. Redlining not only made segregation legal again, but it also worked to intensify the wealth gap along racial lines. After years of disinvestment, redlined communities become economically depressed and typically stigmatized as ‘bad places’.”

Zora was first brought to North Omaha by soul food (a type of Southern American cuisine originally developed by African slaves): “My partner and I had dropped off a friend at the airport in Omaha, and I had been craving soul food, and I thought since Omaha was a bigger city than Lincoln—where I currently live and attended graduate school—that we’d be able to find a good soul food restaurant. We found Lonnell’s restaurant in North Omaha. Rather than getting back on the interstate to head home, we drove through the neighborhood. It was the first time since I had lived in Lincoln that I had been in a place where I was surrounded by people who looked like me. I also noticed the state of the neighborhood, especially where you could tell a business or home once existed, but was no longer there. I knew that I had to learn more about that place.”

“One of the first things I found during my research was North Omaha’s rich history—how black people had made this place into something special and beautiful: the jazz club that hosted names such as Duke Ellington and Count Basie; The Omaha Star, Nebraska’s only black newspaper; that it was the birthplace of Malcolm X. Then I learned of the lynching of Joe Coe in 1891 for allegedly raping a white woman, the lynching of Will Brown in 1919 over the same allegations, the murder of Vivian Strong by a police officer in 1969. Such an intense history of violence. Then I discovered about redlining, and came across this really great article Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism of the Poor by sociologist Rob Nixon who talks about fast violence (often physical) and slow violence (subtle acts of harm that manifest over long periods of time). I saw redlining as a form of slow violence, and that violence was now visible in the landscape. I thought I could use photography to explore that history and create a conversation about it.”

After researching the history of North Omaha, it was time for Zora to go there and explore it in depth, “through visiting the neighborhood, walking around, and talking with people who live there. Like my experiences of working with people, I began to become more present, more sensitive to the things I saw and the information that I could garner from them. Every time I visited North Omaha, I took the freeway/interstate to get there. What I didn’t know initially was that the freeway was supposed to be built through a white neighborhood, but then the residents of that neighborhood banned together and convinced the government to build the freeway through the black neighborhood. Its construction splintered the community, and many families were displaced because of its trajectory. Lake Street, the main business corridor through North Omaha, was how individuals traveled North, and with that came support of black owned businesses. But the freeway diverted traffic from Lake Street. There’s also noise pollution and air pollution from the freeway itself. This is one of many forms of oppression that are in the landscape, but it took me having a critical eye about these things to understand what the landscape was telling me. It was then my task to make a body of work to speak on that idea a little more clearly.”

Zora looked for inspiration in works by artists “who were also using art as a tool for social criticality, including Toyin Ojih Odutola, Alexandra Bell, William Pope L., Bill Gaskins, Wendel White, Dread Scott, and Ken Gonzales-Day. I was also reading people like James Baldwin, Leigh Raiford, Ira Katznelson, Michelle Alexander, Isabel Wilkerson and Teju Cole. I guess while I have a lot of visual references, inspiration doesn’t only come to me visually, and the work of scholars and writers who speak truth to things such as the construct of race and white supremacy, was very influential on the work (e.g., helping me understand how a freeway can physically oppress while simultaneously be a symbol of oppression).”

In general, Zora’s main interests as a photographer “are probably rooted in my experiences studying psychology and working in the human services field. I’m an empathetic person—which is why I probably found myself in those fields anyway—and learning deeply about other people and how they navigate through the world definitely translated into my artistic practice. Working in the criminal justice system taught me a lot about stigmatization, how it is employed to oppress, and the effects of that dynamic. In those professional roles, I was tasked with trying to help people to process and understand that trauma, but also working with them to come up with plans on how to best navigate it. While I was in it, I wanted to figure out how to tell stories about injustice, and art—primarily photography—became my conduit.”

Zora’s #threewordsforphotography are:

Personal. Political. Present.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2024