Looking West — Laurence Watts Explores Australia’s Rodeo Subculture

Looking West by 30 year-old Australian photographer Laurence Watts is, as Laurence himself puts it, “a documentary work that explores masculinity in Australian rodeo subculture. In late 2017 I was living in a country town about three hours west of Sydney. I decided to apply last minute to the Honours degree in Photography at RMIT in Melbourne. I had to submit a project proposal, and the idea to do a series on rodeos kind of came out of nowhere” Laurence says about getting the idea for this project.

“I’m not entirely sure why I chose this subject matter, but I think there were a few things that influenced the project’s conception. For one, I had been interested for a while in working on a major project that focused intensively on a particular subculture. I’m a fan of that Louis Theroux/Jon Ronson style of journalism, and liked the idea of exploring an entirely unfamiliar social sphere. At the time I had also been really drawn to two particular photographic works: Niagara by Alec Soth and Fuji by Chris Steele-Perkins. These series both contain a symbolic (and literal) center-point of a national landmark which appear in certain images but also act as a thematic touchstone from where the works depart, exploring wider ideas regarding life in contemporary society and national identity.”

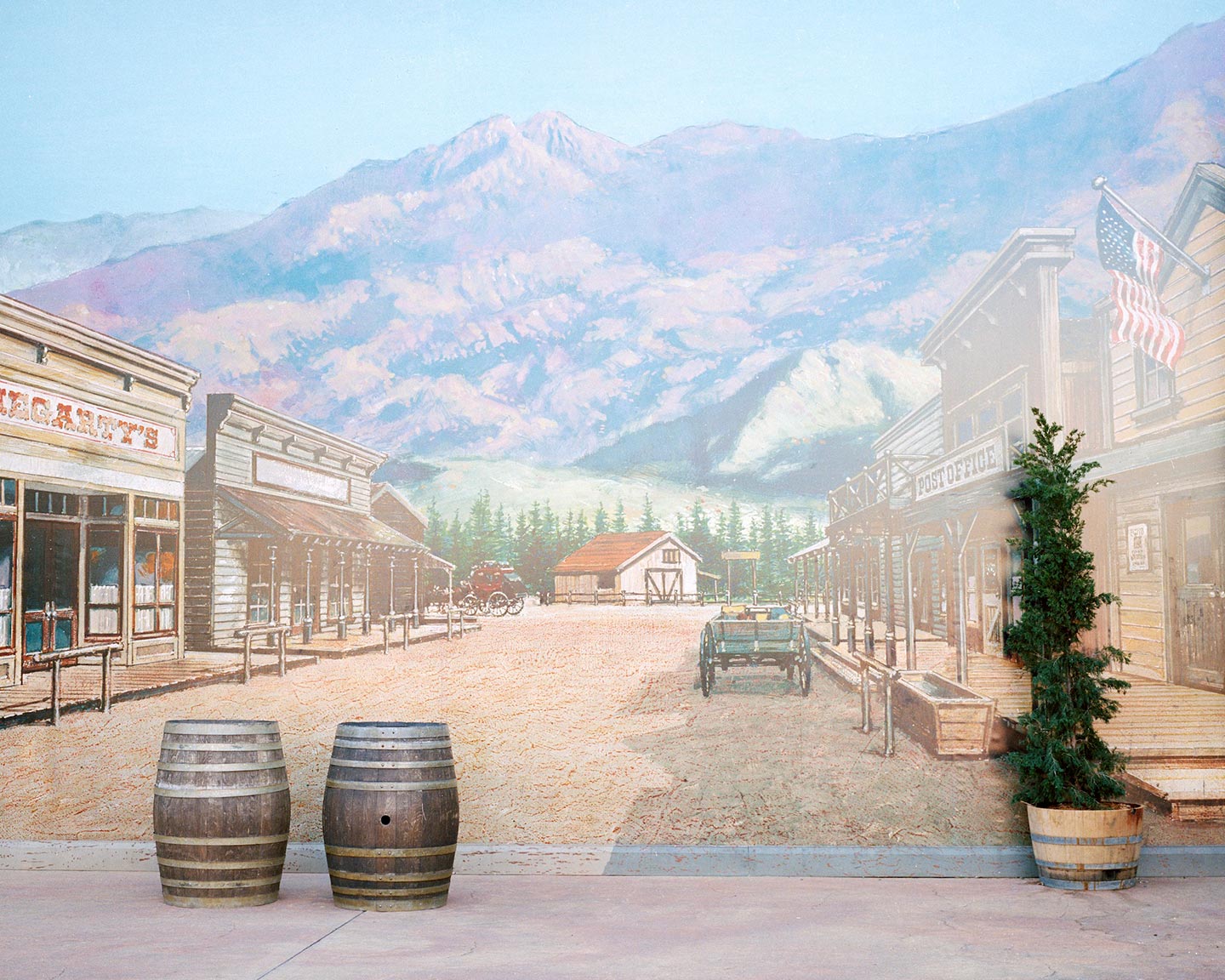

“As a subculture, the rodeo is interesting as it has a very clearly defined center-point of the rodeo ring, out from which extend the lives of the members of the rodeo community. I think in the end I may have digressed from this structure a bit, but something I kept was the sense that for this project I didn’t need to show the rodeo ring at all, or even people riding bulls. I tried to make images that would engage with the viewer’s pre-existing connotations of the figure of the Cowboy and the mythology of the American West.”

Of the images, Laurence says that “the work is about masculinity and the way in which gender is socially performed—I spent the first few months of the project experimenting with different means through which to render these themes visually. Ultimately, I formulated the idea of the work having this kind of non-explicit narrative through-line in which the series itself acts as a ‘search for The Cowboy’. The point here is that The Cowboy, with a capital ‘C’, does not exist in the real world: he is a cultural ideal defined by a particular visual form (hat, boots, chaps, belt buckle). Similarly, ideals of masculine identity do not exist in the real world. Gender identity exists in a social performance that approximates a certain set of traits of what constitutes a ‘real man’, for example. If we go out looking for The Cowboy we won’t find ‘him’, but we will find individuals for whom this figure provides a script through which they articulate their masculinity. So, in making the work I looked for images that spoke to the idea of searching, that depicted visual traces of the-cowboy-as-cultural-icon, that individually touched on issues related to masculinity, and of course plenty of portraits of bullriders.”

Besides Alec Soth’s Niagara and Chris Steele-Perkins’ Fuji, Laurence also used Deep Springs by Sam Contis, Redheaded Peckerwood by Christian Patterson, Wall of Man by Yvonne Todd and Touching Strangers by Richard Renaldi as sources of inspiration. He also had non-photographic references in mind, including western novels such as The Crossing and All The Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy, and Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry; classic western films like Stage Coach, Shane, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly and No Country for Old Men; and the documentary Chainsaw: Bull Born Bad by Shirley Barrett (“a great starting point for the subject”).

“Whilst I had a fairly decisive approach to making and structuring the final work, I don’t have a particularly defined response that I want viewers to have” Laurence says. “I’m a big believer that the meaning of a work becomes entirely out of a creator’s hands once they present it to viewers. I really tried to keep it as much open as possible, to create a space which spurs thought, as opposed to just presenting a conclusion. I do think if there is one thing that is important for me, it is that I hope viewers look at my subjects with empathy. This is not a work that tries to say, “Isn’t it crazy how these guys dress?”. I think that we all perform our identities within our respective social and cultural spheres, and that the parameters of these performances are largely informed by visible ideals of identity. Within the context of this project, the rodeo was just a visually distinct space in which to explore these dynamics.”

So far, Laurence’s interests as a photographer have revolved around “the ways in which identities are formed within a culture, and how these become manifest visibly. Moving forward, I’m particularly interested in questions of truth and authorship regarding the visual material that permeates our daily existence; how changing notions of truth are shaping the way people think and behave; and what role photography plays in this.”

When asked about the influences on his practice, Laurence answers that “I want to avoid just writing a list of photographers, visual artists, writers, musicians, etc. I think that for me, photography has always come out of a curiosity about the world and about the relationship between how things ‘look’ and how things ‘are’, and whether or not we can access the latter through the former at all. Growing up watching way too much television also definitely had an impact on me. I think this is a huge aspect of the way my generation grew up and learned to see and think about the world. We internalized all of the tropes and archetypal characters of crappy television, and these became a frame through which we interpreted our experiences. Ultimately, for those of us who went into the arts, the conventions of mainstream visual entertainment have become something many of us engage with in our creative practice.”

Some of Laurence’s favorite contemporary photographers are Sam Contis, Max Pinckers, Daniel Arnold, Xiaopeng Yuan, Laia Abril, Swarat Ghosh, Alec Soth, Mitch Epstein, Peyton Fulford, Lila Barth and Bieke Depoorter, “to name a few.” The last photobook he bought was Margins of Excess by Max Pinckers, and the next he’d like to buy is Dyckman Haze by Adam Pape.

Laurence’s three words for photography are:

How. Things. Look.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025