Living on the Line of Fire — Marcel Maffei Documents Daily Life Along Ukraine’s Frontline

A few weeks ago, photographer Andrey Lomakin showed us how many civilians across Ukraine have been acquiring a weapon for personal defense as a response to the tensions generated by the conflict with Russia. 30 year-old German photographer Marcel Maffei now brings us right on the conflict’s frontline: his subjective reportage Living on the Line of Fire captures how this forgotten war is severely affecting the daily life of those who live close to the battlefield.

Hello Marcel, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Hey, thank you for showcasing my work! I’d say photography for me is about exploring and telling stories, finding topics that combine my personal interests and my practice, diving into something unknown and recognizing the theme for myself.

Please introduce us to Living on the Line of Fire.

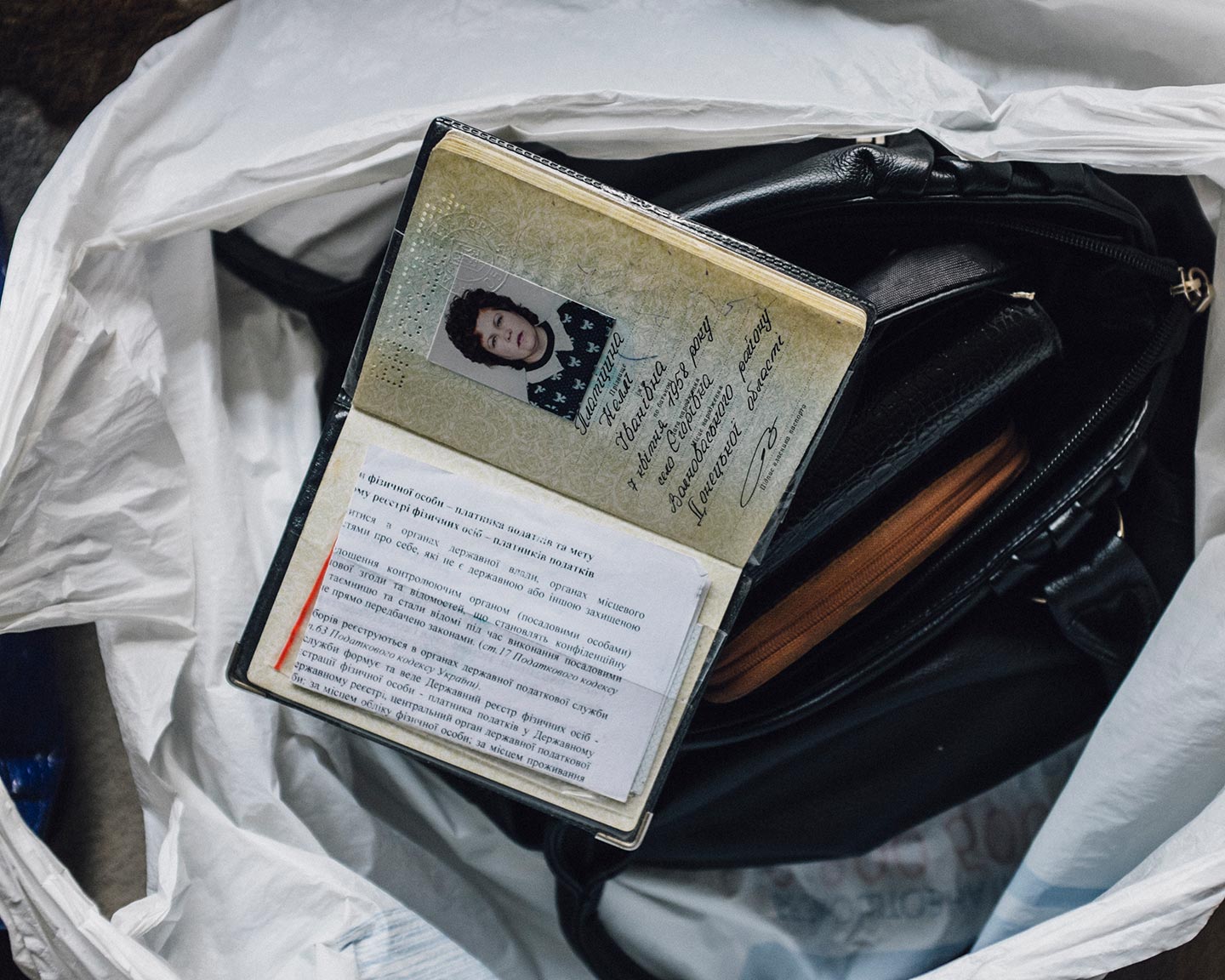

Living on the Line of Fire is a documentary essay shot on the frontline in eastern Ukraine, and more precisely in the Donetsk area. It focuses on the people who, for different reasons, still live in the so-called “grey zone”. It captures the mood and atmosphere of the place as I experienced it, and explores how the conflict may even not be visible at first look. I tried to take pictures that were not too obvious, and in a different style than the classic reportage work.

Why did you decide to capture daily life in Eastern Ukraine?

I traveled to Ukraine with a few ideas on how to cover the conflict. My main motivation to go there was that the war was—and still is—underreported. Nobody bats an eye about this conflict and the people suffering from it, even though Ukraine is the biggest European country. At the very beginning of my time in the country I worked with displaced families who have found refuge in Kiev; it was during that period that I decided I really wanted to go to Donbass and document the daily life of those who still lived on the frontline. To be honest, I’d never been in a conflict area before and I had no idea what to expect.

Can you make a few examples of how the conflict has changed the life of your subjects? What adaptations did they have to make?

A conflict changes many things. It goes from losing or getting separated from your family, friends and all your loved ones, to having to live without the most basic services. In some parts of the smaller towns electricity and water supplies have been restored again only recently, after a long time when they weren’t available. The people of the villages use their basements—if they have one—as makeshift bunkers to hide from shelling. Everything is improvised because there are often no alternatives. Everyday, people wait for the UN soldiers to deliver water and bread: their life constantly depends on others.

How would you describe your approach to the work? What did you want your images to communicate?

I tried to show the conflict through the use of metaphors. For example, the landscapes suggest that actions of war have taken place, without showing them directly. On the frontline, it’s important to take a second look: some things may seem pretty normal, but they are actually dangerous—a typical backyard or cornfield can hide a minefield or explosive traps. I wanted to show how banal, daily things and places can suddenly become dangerous and turn into something frightening. On the other hand, I tried to capture the feelings of tension that I could sense and read on the faces of people who have had to live in such a condition of constant danger for the past years.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Living on the Line of Fire?

I didn’t have a specific source of inspiration, but in general I was inspired a lot by music and literature during my time in Ukraine, which was quite uncommon and new for me. I mostly wandered around all day listening to music, which helped me take a look without making pictures. Observing daily life was my main inspiration.

How do you hope viewers react to Living on the Line of Fire, ideally?

The most important thing for me is to make viewers dive into the mood and emotions of what is shown, and to make them sense what the story is about.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

It was my time at the Danish School of Media and Journalism. I learned so much about myself and how to improve my photography by putting more of myself into my work. Our mentors would give us extremely challenging assignments—we were invited to cross our personal borders and try to encounter our fears, visualize them with photography and evolve. We were encouraged to push ourselves past our limits. One of the main things I was taught was to be a responsible and respectful person to the people you photograph. I guess working on documentary or reportage projects is like a boomerang: you get back what you give.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

It’s pretty hard to only name a few, but here you go: Alec Soth, Antoine Bruy, Bryan Schutmaat, Rafal Milach, Andrea Diefenbach, Pieter Hugo, Masahisa Fukase, Donald Weber, Rineke Dijkstra, Todd Hido, Hannah Modigh.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Kindness. Listen. Patience.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024