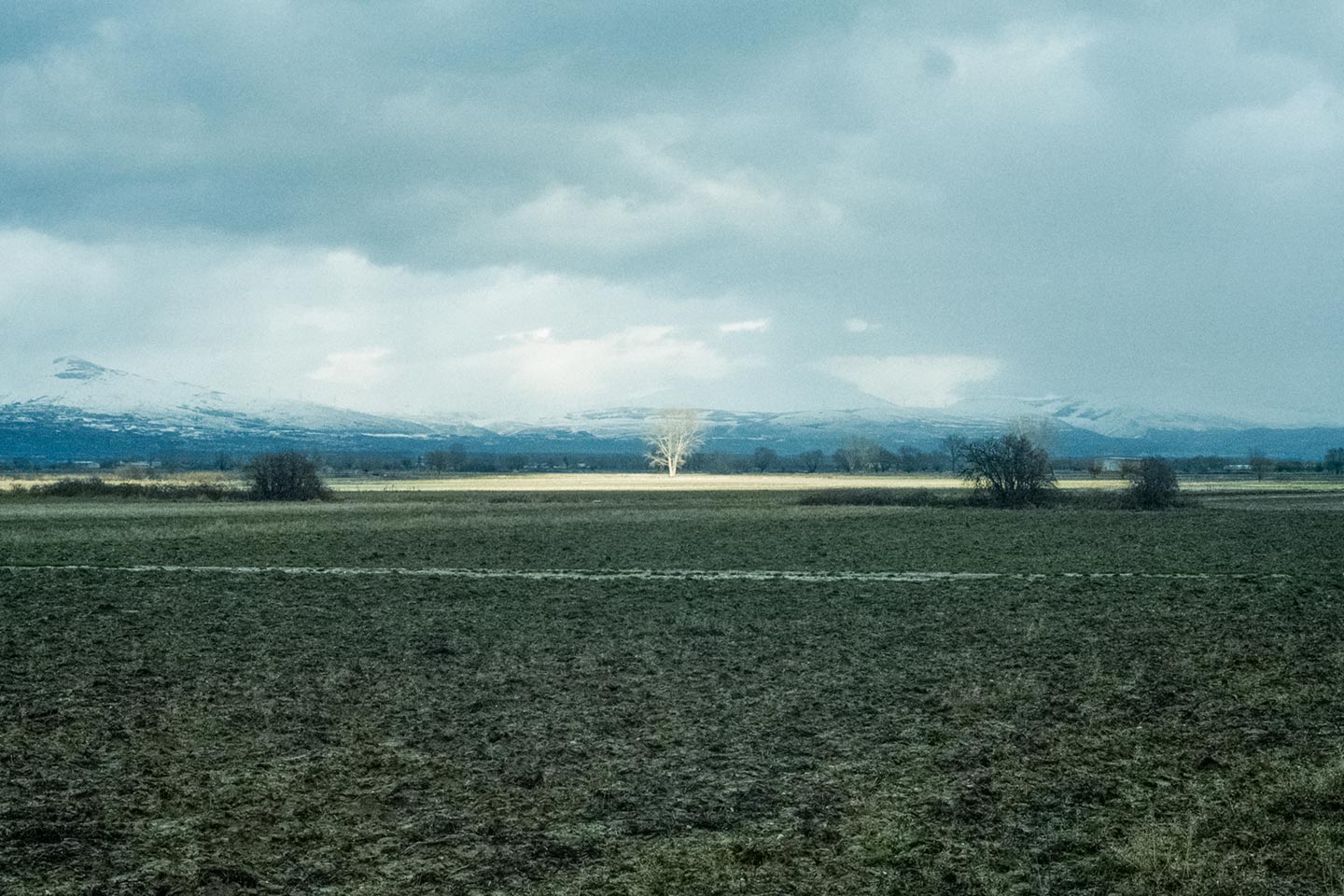

Enrico Di Nardo Captures the Mystery of a Territory That Used to Be at the Bottom of a Lake

With an extension of about 145 square kilometers, the Fucino lake used to be Italy‘s third largest lake, until it was completely drained in the second half of the 18th century to put an end to its recurring overflowing. The territory that used to be at the bottom of the lake is now a vast rural area, but 32 year-old Italian photographer Enrico Di Nardo felt a sense of mystery in the place, a sort of echo of the time when that land was covered with water, which he decided to capture in a series of fascinating landscape photographs called Lifting Ground Shadows.

Hello Enrico, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I’m interested in whatever confronts us with the limits of our ability to make sense of the world that we perceive. We don’t see what is before our eyes, we see what our mind tell us is there. I enjoy the suspension state of uncertainty, the uncomfortable tension generated by the perception of the unknown, the mysterious, the unpredictable. Independently of the specific subject, the place I find thrilling to be is at the margin of what is not comprehensible, where meaning is not self-evident and interpretations are not obvious.

As a photographer, I believe that illustrating what is immediately understandable is condescending, at worst plainly boring. Things get interesting when a sense of elusiveness keeps our curiosity in unrest, leaping sideways from the reassuring need to reconcile what we see with what we already know.

Please introduce us to Lifting Ground Shadows.

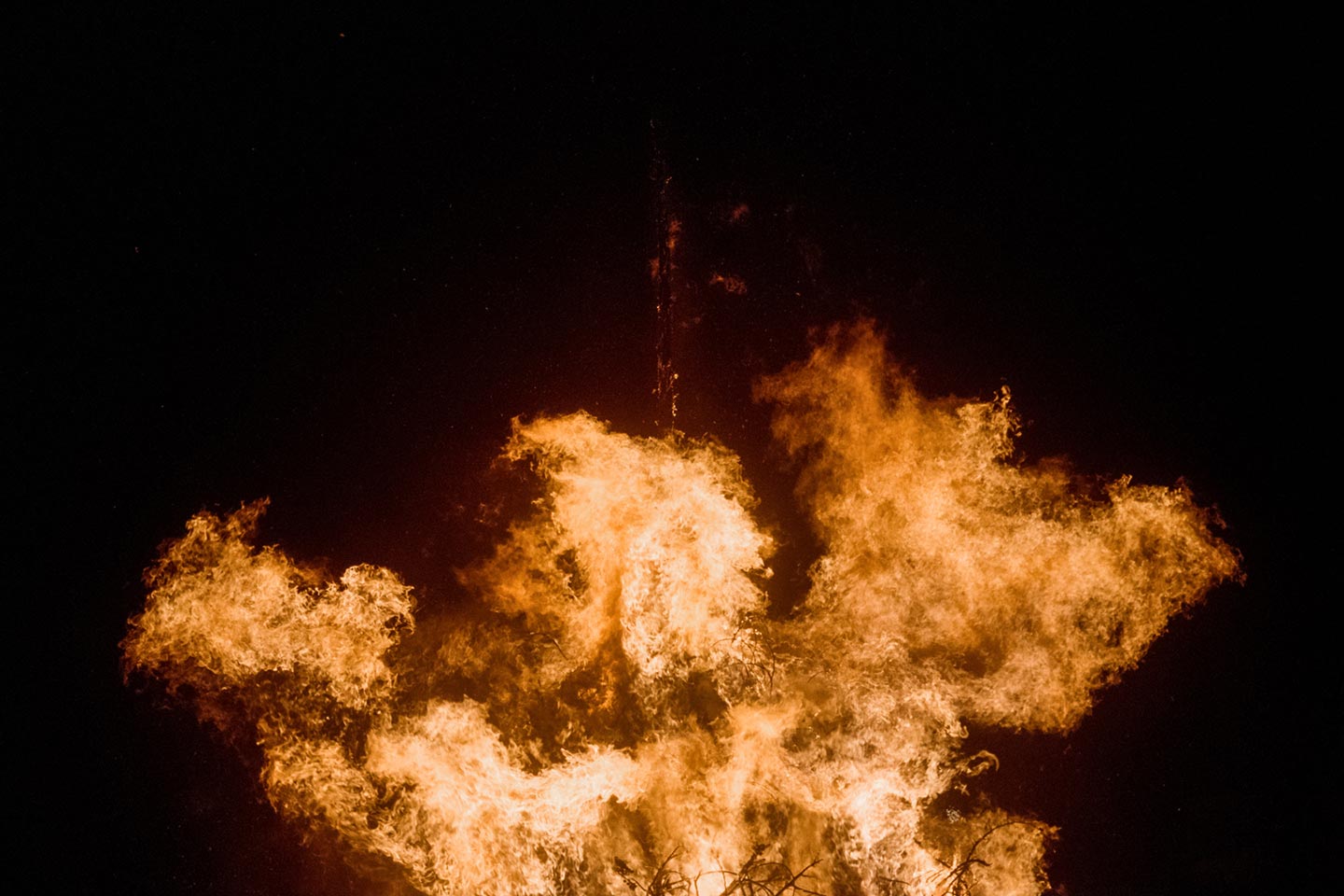

It is a journey through an anomalous place, a place that should not even be there hadn’t human intervention tampered with natural order. There is something uncanny about this stretch of fields, probably because until 140 years ago all this territory was underwater, at the bottom of the Fucino lake (Italy’s third largest lake). The artificial draining yielded a territory that seems to retain a sense of hostility despite its domestication, a sort of eerie resistance.

How did you find out about the story of the Fucino lake, and why did you decide to make it the subject of your project?

The Fucino area is about an hour drive inland from the place were I grew up. During car trips with my family, it was not uncommon to ride on the road running along the former north shore of the lake. As adults usually do with kids when there is something peculiar around, my father used to draw my attention towards the big parabolic antennas of the space communication center far away in the plain, telling me that once it was all covered with water.

A few years ago I happened to drive alone through the area—the spooky atmosphere which I felt there was as unsettling as captivating, and I was enthralled by those indistinct yet densely present sensations. I guess that what was drawing me to that place was the sense of mystery it irradiates: in its essence, it is the completely other, the alien, the extraneous, what fills us with amazement, what is beyond usual, understandable, familiar, and for this reason hidden, absolutely out of the ordinary. The fact that all this was shining through a seemingly ordinary rural area resulted in a perturbing ambiguity which was extremely attractive to me.

Indeed, more than strictly documenting the Fucino area, your images seem to capture a personal feeling you have of the place. How would you describe that feeling?

To me, “strict documentation” means resorting to a visual register and a set of stylistic codes which have emerged from the intention to achieve some sort of objectivity. I’ve never had any aspiration in such sense despite I might occasionally borrow certain visual aspects which are proper to that approach. Experiences are inescapably subjective, and photographs are artifacts that cannot but be filtered by our individuality. It really does come down to what is in our imagination, to the feeling brought about by the situation we engage ourselves in, and how we respond to it.

While roaming in the Fucino area, I had the constant, subtle perception that something extraordinary and incomprehensible happened there—it elicited a blend of wonder and apprehension, tinged with awe. However, I think the question is never whether personal feelings are captured or not through images, because they always are. The more interesting point, I believe, is instead about the role of feelings in delivering the subject and the visual forms in which feelings are articulated to do it.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to the work, photographically speaking? What kind of images were you looking to create?

In my experience, whenever the crafting of the image is dominated by the intention to produce a sought after result, it often ends up in disappointment. I think that an effective image arise from the effort in concentrating on the source of our engagement, as a collateral effect—whether it is staged or not does not matter. My foremost concern is then to immerse myself within the situation, I deem it is the necessary condition (although not sufficient!) to let the image be charged with the questions one’s dealing with. Of course I always end up with a wide variety of photos, and the kind of images I am looking to create become clear to me retrospectively, during the stage of editing. It is the conception of the series as a whole that inform the answer to the question.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Lifting Ground Shadows?

What could have been influential visual references becomes manifest a posteriori, in the images. There, anyone can find, more or less evident, the shades of the references that had struck my imagination, and to which I unconsciously refer to. Initially I was not deliberately keeping in mind any specific source of inspiration, but at some point I started feeling some analogies between my exploration of the Fucino area and the journey inside the Zone of the characters in Andrej Tarkovskij’s 1979 film Stalker: the Writer, for instance, goes into the Zone to meet the unknown and be amazed from it, as an antidote to the boredom of a world dominated by immutable laws. Tarkovskij said that “the Zone is not a symbol of anything, the Zone is life: passing through it, man breaks or resists. Its ability to resist depends on the feeling of its dignity and its capacity to distinguish the fundamental from the transient.” I think that Stalker has helped me to reflect more on the reason why I was doing this project instead of inspiring my vision—which it certainly did to some extent anyway.

How do you hope viewers react to Lifting Ground Shadows, ideally?

I’m satisfied as long as the viewers feel transported in the dimension I’ve crafted through the images and have an engaging experience of their own reactions. Informing the viewer about the history of the lake Fucino, or showing its peculiar features has never been my goal; it is incidental. The empty lake bed is not intended to serve the purpose of a narration or an illustration: it is an expedient to raise the psychological experience of the unintelligible within the seemingly commonplace.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I don’t know. The way we look at things is a construction emerging from fragments of everything that has previously been seen and experienced: the mind absorbs, recombines and rejects in ways that can be are hardly recognized. To what extent something is more relevant than something else in the creative process of picture-making is largely unconscious, and quite impossible to tell for me. I have really no means to say whether the main influences on my photography should be attributed to growing up in the suburbs, the vision of a certain artist’s work, rather than to my scientific studies, an encounter, the grief for a loss, the light of my hometown during summer, the experience of frustration, Facebook’s daily photos stream… I really can’t say.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Lieko Shiga, Wolfgang Tillmans, Todd Hido, Torbjørn Rødland, Taiyo Onorato + Niko Krebs.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Synchronicity. Unforseen. Transformation.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025