Brooklyn Is in The Details — A Visual Study of the Borough’s Textures and Materials

26 year-old Russian born, Canadian photographer Arseni Khamzin discusses JMZ, a brilliant series of photographs that looks in detail at the materials, textures and colors found in Brooklyn, New York.

JMZ is also available as a self-published photobook—buy your copy here.

Hello Arseni, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I feel like my relationship with photography changes pretty regularly, but these days one of my main interests is using photography as a tool to slow down and look closely at what’s in front of me and be really present with my subject, whatever it may be at that moment.

Please introduce us to JMZ.

JMZ began in 2013 after I moved to Brooklyn, New York from my hometown Vancouver, Canada. For the project, I spent a year and a half taking long walks through the streets of my neighborhood in inner-city Brooklyn and photographing the objects, spaces, and people I encountered along the way. This project was my way of interpreting a new landscape that I was encountering and looking closely at for the first time. I was a stranger in a place that had stood before me for hundreds of years, and I felt like I was coming to it with fresh eyes and trying not to take it for granted. Because of this I think I saw a lot around me that I couldn’t easily explain or understand, especially in the details of how the city was built over time and in the subtle differences between areas.

I used photography to try to understand the unfamiliar landscape that I found myself a part of and express the sense of awe, wonder, and confusion that I experienced in this landscape.

What inspired this series, and what does the title JMZ mean?

One of the biggest inspirations was the experience of traveling for a year prior to moving to Brooklyn. I spent a lot of time thinking about what made cities unique and about what certain areas within cities had in common. I got to see a lot of places in Africa and the Middle East but also in Europe and the US. I think I developed an idea that many nuances were inevitably expressed in really basic, everyday forms that we encounter all the time, and this was something I started to consider a lot.

For the title, JMZ is based on the name of the train lines in Brooklyn along and around which many of these images were made during my walks.

Can you talk a bit about your creative process for this project?

Walking was important to making the work – I would go on walks with my camera while I explored my new surroundings. The neighborhoods I roamed were comprised primarily of working-class residential, small businesses, and semi-industrial areas. I would walk into cul-de-sacs and in between buildings, move along train tracks and canals, and follow dead-end roads into industrial fringes; I would venture down desire paths carved through empty patches of land and find myself moving through the courtyards of vast housing complexes. I walked during sun and snow, sometimes on grey days, but usually looking for days with good light. It was during this process that I was taking images regularly.

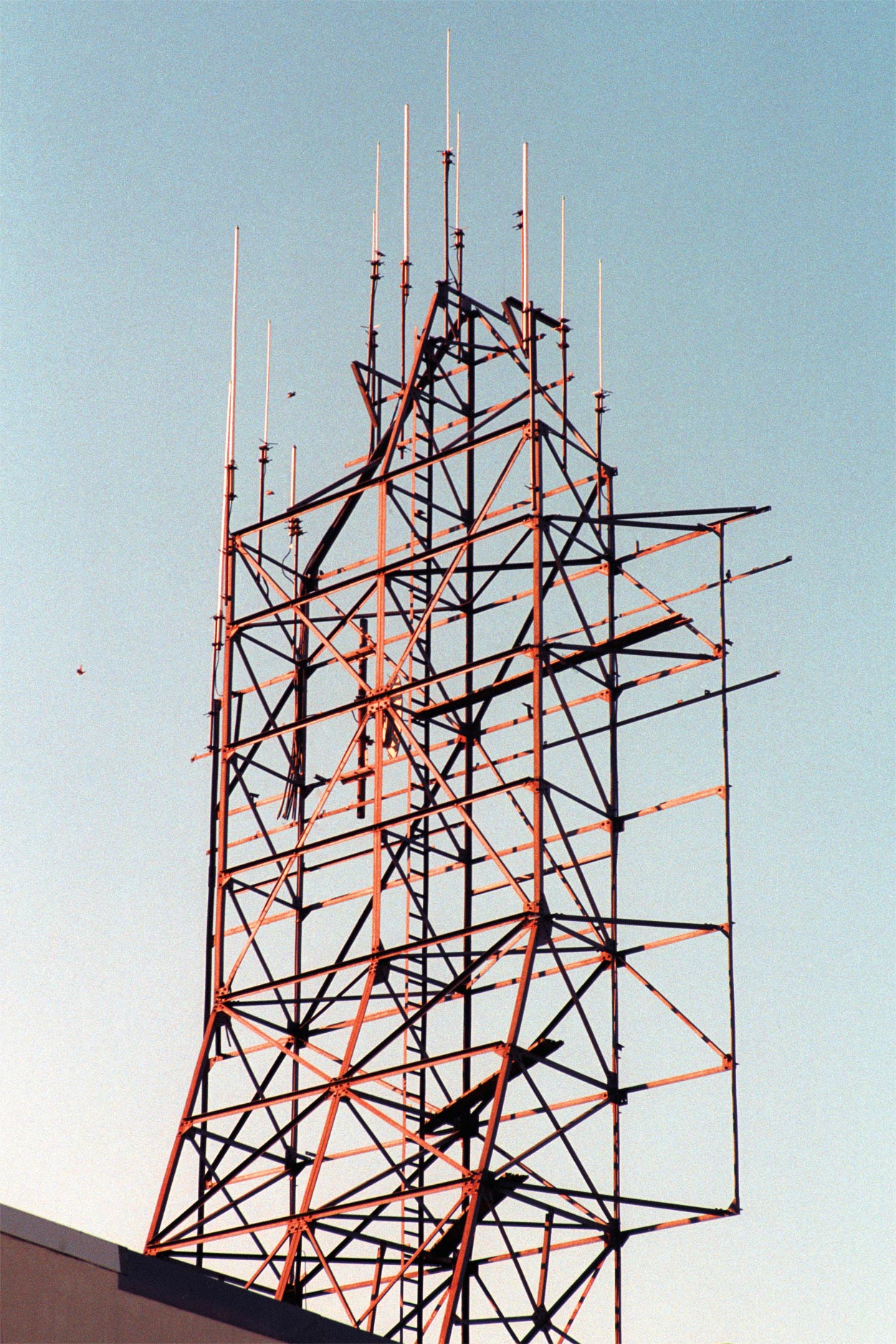

I chose to use an 85mm telephoto lens because it was quick, sharp, detailed, and had a much narrower angle of view than I was used to. An important but unintended effect was that this camera-lens combination changed the way I saw my surroundings, and therefore, the way I moved through the world. My embodied experience with the camera led to a tendency to isolate specific elements in the urban landscape instead of trying to depict spaces in a broader view. I feel this is partly what led me to focus on the forms and details that I did. I also used an on-camera flash, especially during daylight to create a competing angle of illumination.

After I made pictures, my editing process involved scanning my negatives digitally and adjusting for color, luminance, saturation, and contrast. Some of the photographs were converted to black and white in the post-processing stage; others were cropped, either to remove distracting details creeping into the frame, or to change their aspect-ratio to create more dynamic compositions. I would then make two copies of each image as 4×6” prints at the drugstore, one of which I would put up on large boards to look at for the next few weeks, and the other which I would keep for book dummy or collage purposes. Eventually, this became hundreds of pictures to live with and to make selections/connections between.

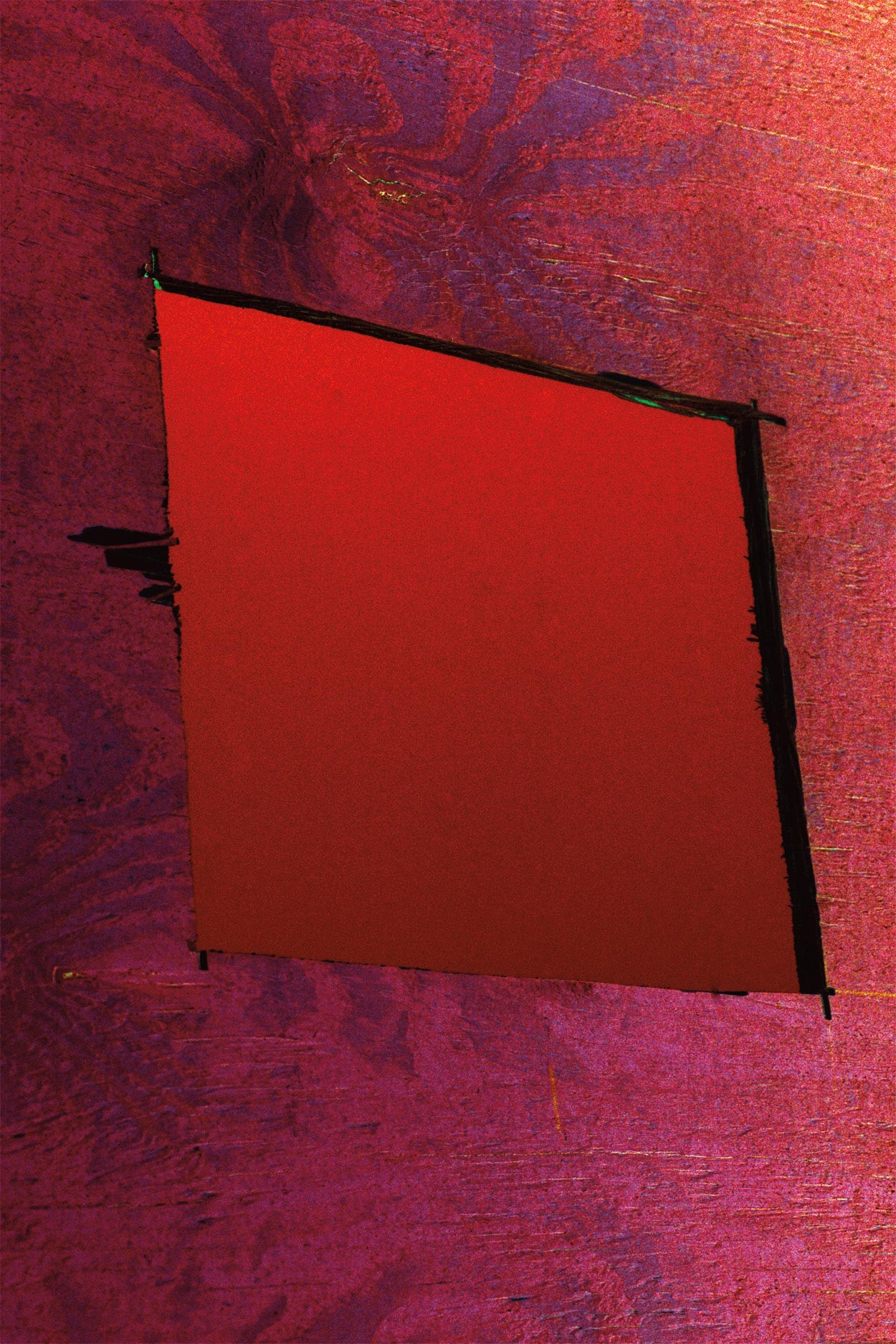

Why did you focus on details that indicate a degraded urban environment like rusty surfaces and broken windows?

I don’t think that suggesting a degraded urban environment was necessarily my central focus, but I think that as a whole I was really interested in materials, and in how they looked as they evolved over time, or in how they were modified with newer, and more current materials. Brooklyn as I encountered it was vastly different in its material presence as a city than what I’d been used where I grew up. Because everything was new to me, I began to pay closer attention to things I normally overlook on a street: the type of debris that collected along the curbs, the design of plumbing fixtures that jutted out of buildings, the materials used to patch breaks in foundations and the implements that were used to fortify a space. I was drawn to these elements because on one hand, they were common and unassuming, especially to someone who’d always lived there; but on the other, they had a kind of unintentionally quiet and humble beauty.

I was struck by elements that recurred in large numbers in the landscape: giant steel husks that acted as billboard frames, decaying lengths of razor wire, endless varieties of corrugated aluminum and plywood, piles of tires propped against seedy “flat-fix” shops, as well as the numerous iterations of surveillance cameras and spotlights. The makeup of materials that were used in building homes, businesses, and on the streets was novel to me and out of sync with what I experienced in many other major cities in the developed world. For the most part, what stood out to me was an abundance of components that were temporary, cheap, and disposable, and that these were placed in the environment as substitutes for more permanent materials. The visual appearance this took on was less of what I expected to see in a major city in the developed world, and more of something I’d seen in cities like Nairobi or Bangkok.

At the end of the JMZ book you express your thanks to people like Alec Soth, Mark Steinmetz and Ute Mahler for mentoring you through the project. That’s a hell of a list of mentors to have! How did they help you?

It’s really difficult to choose who to thank in a colophon! While I was at Hartford, I was incredibly fortunate to have had access to some very perceptive and intelligent image-makers who gave me feedback on my project during its earlier stages. Alec, Mark, and Ute were among the people who asked me some really difficult (and necessary) questions about the work that I think helped shape my thinking and approach for the decisions I made moving forward. There were many such people who did this, but for me, their advice, questions, insistence, and understanding of the work stood out in particular when I reflect back on this time.

The series mixes color and black and white photographs. Why is that, and why in the JMZ book did you keep all the black and white pictures for the final part of the sequence?

The work was all shot on color negative film, but in the process of reviewing each image, I took an intuitive approach to editing the photographs. Sometimes, I didn’t feel like the color was strong enough in the image, or it felt distracting to the other formal qualities in the photograph, but that it worked better as a photograph in black and white.

After producing many early book dummies, I developed an idea of the basic kind of sequencing and pacing that I wanted in the book, and mentally devised a rough order of which images I wanted to start and end with. In this case, my choices for the last few images happened to be black and white. Because there were only about 5 pictures like this, I decided it felt better and more coherent to leave them to the end instead of scattering them through the book.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on JMZ?

When I began the work, I read Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities and it was a strong point of influence in thinking about cities and how to understand / conceptualize them. I also stumbled on a textbook by Guiliana Bruno called Surfaces: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media that helped me think about superficiality and about materials as a whole, and changed the way I was thinking about this work. I was also exposed to a lot of different projects in New York and I think that sculpture and installation had big effects on me. The collection at DIA Beacon and American sculptor John Chamberlain’s work also really interested me while I was working on the project, but so did stuff like Jonah Freeman’s and Justin Lowe’s works.

Photographically, I was looking at a lot of different things, but among them the ones that stood out were Camillo Jose Vergara’s Invincible Cities, a work that documented Harlem and parts of NY/NJ from the 1970s to the present. Also, Will Brown’s photographs from the 1970s. Trevor Hernandzez (@gangculture) is an instagram artist whose feed I discovered mid-way through the project and felt like we were looking at similar things on different coasts. I also really like Nico Krijno’s work and I’m sure that his visual influence crept in on my own work over time.

How do you hope people react to your images?

I hope that they look at and think about what makes the place they live in look the way it does.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Travel, cinema, visual art, literature, and hands-on building.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

In no particular order: Geert Goiris, Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs, Mårten Lange, Torbjørn Rødland, Paul Graham, Taryn Simon, Vivianne Sassen, Katy Grannan, Lars Tunbjörk, Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel – the list goes on…

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Challenges. Accidents. Dust.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2023