In the Shadow of the Pyramids — Egypt through the Experience of Laura El Tantawy

Born in England from Egyptian parents, and raised between Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the USA, it is not difficult to understand why, at one point in her life, photographer Laura El Tantawy has felt the need to go back to her roots in Egypt, in an attempt to reconnect with her culture of origin. But she returned in a critical moment of Egypt’s history, when the country was in the political turmoil that eventually led to the 2011 revolution and the fall of Mubarak.

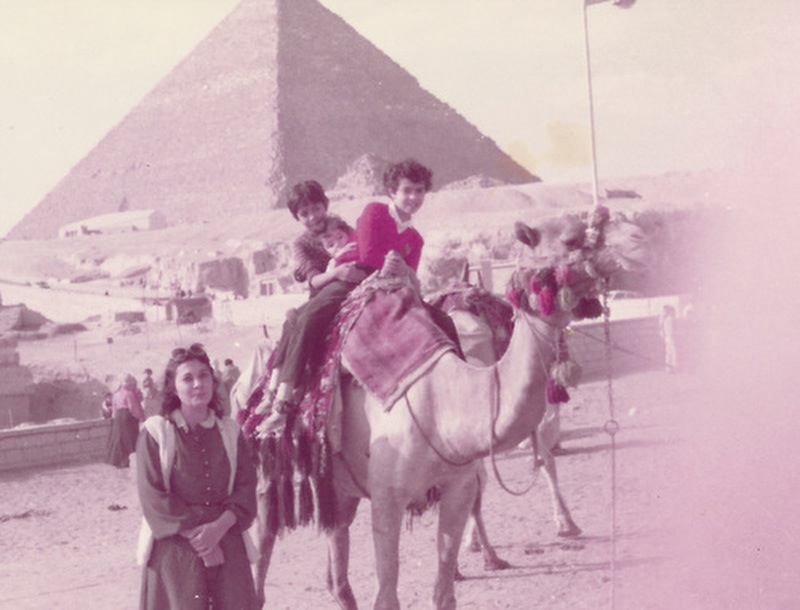

Laura’s first photobook In the Shadow of the Pyramids, – selected by Martin Amis as one of ten best photobooks of 2015 – however, is not a documentary book about Egypt’s recent history. It is rather a subjective view of the country, an expressive and deeply personal account of a young woman – and a talented photographer at that – going back to the places of her childhood.

Visit the book’s dedicated website to order your copy (and if you are a photographer, bookmark the site as a great example of how to present your photobook).

Hello Laura, thank you for this interview. You started working on In the Shadow of the Pyramids in 2005, when you returned to Egypt after being away for nearly two decades. Your goal was to explore the essence of the Egyptian identity to better understand your own. How does one do that by using a camera?

The camera was the tool I used to look in the mirror in order to explore my own identity. It was my excuse to get out on the streets and engage with people. Having these conversations gave me a sense of safety and belonging.

In the Shadow of the Pyramids is your first photobook. The photographs in the book include shots taken between 2005 and 2014, as well as family snapshots from your childhood in Egypt. What were your impressions of the country when you went back after so many years? Were you home or did you feel like a foreigner?

Initially I thought the country had changed but I realized it was me that had changed. I think any time you start to address your own identity you begin to question your upbringing, religious belief, ideology and traditions. But I saw an Egypt on the brink of something big. I was inspired by the young protesters on the streets calling for change. They were so outspoken and courageous and I admired that because I felt it was an energy I thought we were no longer capable of generating as Egyptians.

You were in Tahrir Square that 25 January 2011, when the revolution started, and took impressive photos of the hundreds of thousands invoking democracy. What are your memories of that historical day? What did it mean for you as an Egyptian to be there?

I was feeling many emotions all at once and trying to actively make a decision between taking pictures or taking part in the collective chanting. At some stage, I was also working as a fixer with an international publication to make some money and I could not photograph while helping them, so I remember being overwhelmed by guilt because I was missing pictures.

As an Egyptian, the 18 days of Tahrir Square were the best time in my life. I always go back to those days for all the memories and emotions they left me with.

Part of the photographs of In the Shadow of the Pyramids were taken after the fall of Mubarak. How did the revolution change Egypt? And what remains of the high hopes it ignited now that Mubarak is gone but another authoritarian president, Al-Sisi, leads the country?

I think time will really answer this. But in my opinion, the 2011 revolution gave people confidence in their ability to change the course of their history. Confidence is very important because it was beaten out of the Egyptian spirit. The idea that politics is akin to our fate in the sense that both are predetermined has been shaken.

Some good will come with Sisi, but I don’t believe removing one military figure for another is the way we can begin to address democracy. I disagree with people who say the military are the only ones who can govern Egypt. I find it disrespectful – the idea that people need tough leadership to whip them into shape. Egypt is a country with massive problems, two of which are a tendency towards short-term memory and not believing in our potential as individuals. The latter is an outcome of years of repression, not just from the government, but across the board. In school, my teachers didn’t talk to us about dreams. They talked about the reality that surrounds us and our life had to conform to that somehow.

The last of the brief texts written by you and published in In the Shadow of the Pyramids ends with these solemn words: “Standing in the Shadow of the Pyramids. The beginning meets the end. Here I choose to bury my most valued possession. In a place I once called home.” Why do you no longer consider Egypt your home?

Because my Egypt is far from the one I saw unfold in front of me in the past four years. The Egypt from my childhood was being erased. This is not a book about Egypt, it is about Egypt through my experience. The text anchors this. By the end of 2013 I had seen blood and pain in a way I had not associated with Egypt – I shut down. I couldn’t photograph from a place of empathy or understanding anymore. These two emotions are at the starting point of all of my work. I had nothing to say any more and with that came a sense of loss. The realization that this is not what home means to me was the ultimate end.

Where are you based now? What do you think today when you think of Egypt?

I am not sure where I am based now. I am travelling and trying to find a new base.

When I think of Egypt, I think of love and loss.

In the Shadow of the Pyramids is self-published. Why did you decide to self-publish, and what were the greatest challenges you met in the making?

Self-publishing was the best and bravest decision I made. The current publishing model is one where most publishers are asking authors for the production cost of the book, so I was paying for it anyway. The difference is with a publisher I would not breakeven through royalties. Alone, I will get close – this was key.

As an independent photographer, I am always trying to develop a working model that suits my work and my goals. Publishing within the current framework of book publisher demands is not a sustainable working model for me. I work a second job outside photography to survive financially – now that I am working on my next book ideas, I cannot fathom working the same amount of days and nights as I did to save the same amount of money. So I had to value my hard work and proceed in a way that respects that.

I felt insecure in the beginning about doing it on my own because this is my first book. I was honestly scared no one would buy the book. This is why I wanted to work with a book publisher and I wanted a sense of safety and someone to turn to with questions I had no answers for. I have learned so much and I am still learning.

The greatest challenge is the loneliness that comes with self-publishing and the amount of work it requires. Logically, it seems it would get easier as the book is further developed, but in my experience, every step forward added 10 extra challenges. I am working all the time – answering emails, emailing people about reviews, sorting out shipping, then sorting out shipping problems, then sorting out shipping again, etc. I just try to stay focused on the positive. The most important thing is to believe in the work from the beginning. Having this has allowed me to get through some really stressful stages in the life of this book.

The book “is edited to look like a one night’s encounter”. Can you describe a bit about the book’s structure and sequencing?

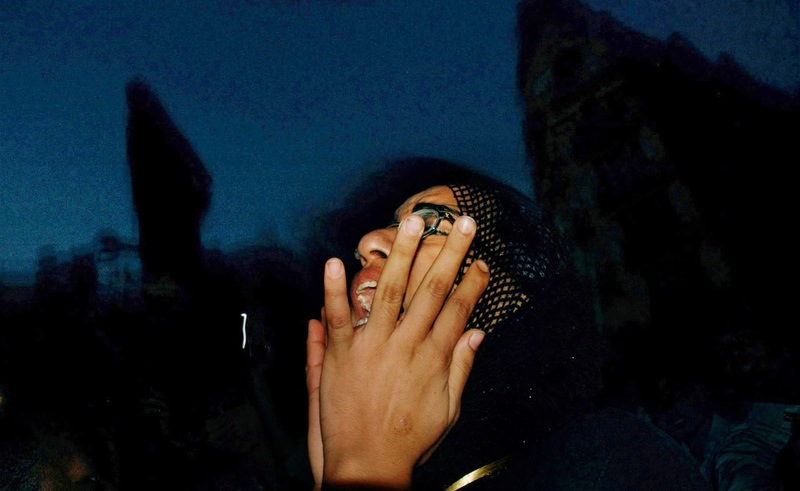

I like books as objects but have always loved books that go beyond that. I wanted my book to be an experience and this is what I discussed with Syb [the book’s designer]. You experience a day – it starts out bright and peaceful and it slowly turns violent, chaotic and at some stage claustrophobic. You feel stuck and you want to get out. The text is intended to anchor this experience. It is not a happy experience – this is intended to be a rough, dark book and the choice of paper, texture on cover, eliminating images of people smiling from the final image selection, all bring this experience together. It is also a sentimental and passionate book, so the Japanese folds and childhood images bring that element in.

Why is this photobook important to you?

Because it’s personal, but I believe all work has to be personal. There are other reasons: the fact it is my first book makes it special. The memories and the idea of finality – the fact that I do not have to confront the conflict of belonging or not belonging anymore. This brings me a sense of peace. Personal closure is the most important outcome of this book.

Choose a photograph from In the Shadow of the Pyramids and share with us something we can’t see in the picture.

There is the picture of the woman and the red hibiscus flower. My mother was standing right next to me when I took it. The woman is not talking on the phone – she is lifting her hand up to her hijab. I took this photograph in my favorite outdoor park in Cairo. I go there a lot and still do when I am back to Cairo. I always go on Friday afternoons just before sunset. It has sentimental value, so do many images in this book. Many have personal meanings because they are photographed in favorite places, bring back memorable sounds or smells or were photographed in the presence of people I care about.

Now that In the Shadow of the Pyramids is done, is there something you know about yourself that you didn’t before?

I am good at generating ideas but not necessarily good at executing them, so I could not have designed my own book as I had originally planned.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Personal. Emotional. Colorful.

You can order Laura El Tantawy’s In the Shadow of the Pyramids from this website.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2024