This Is the Desert Where the Atomic Bomb Was Tested in the 1940s

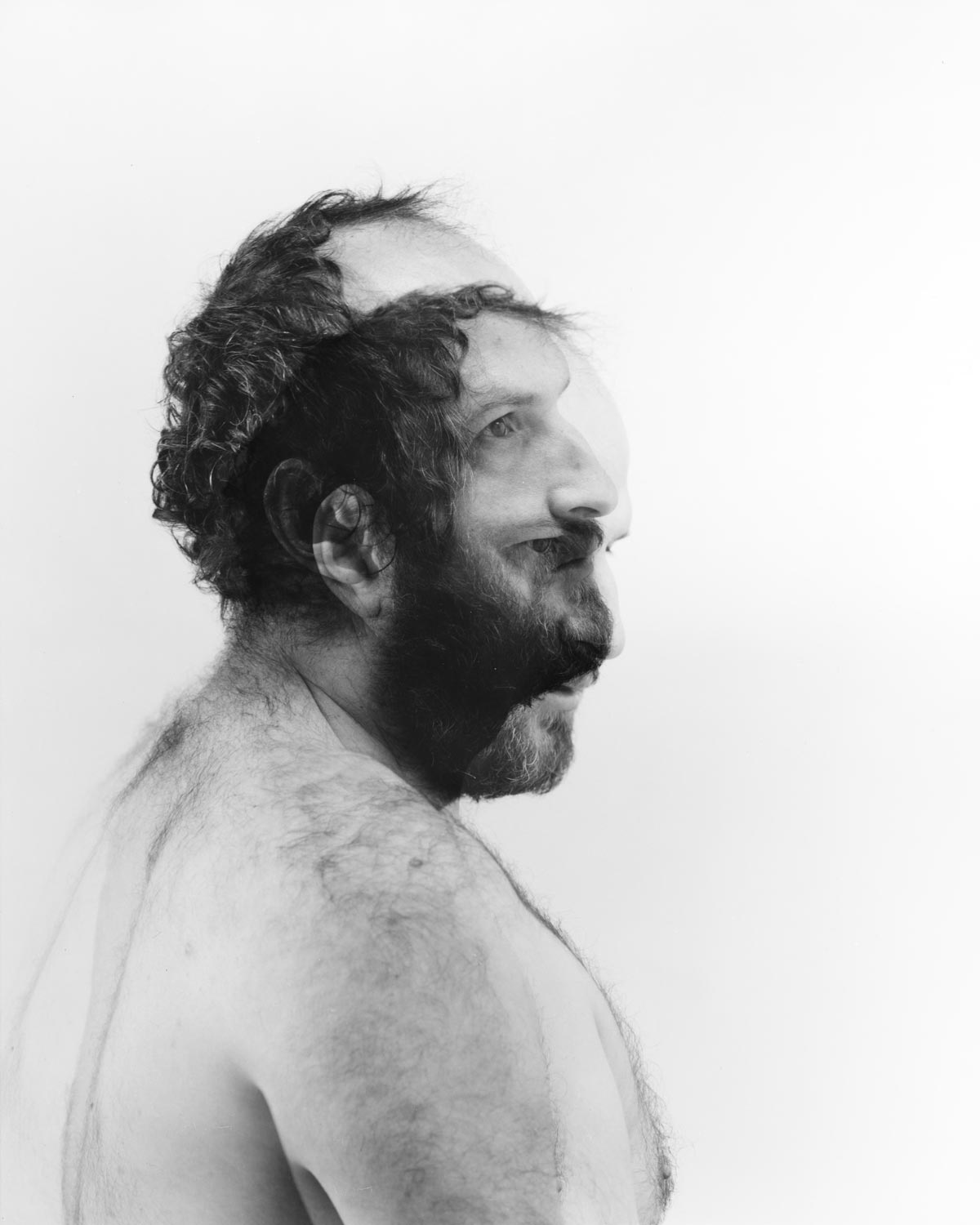

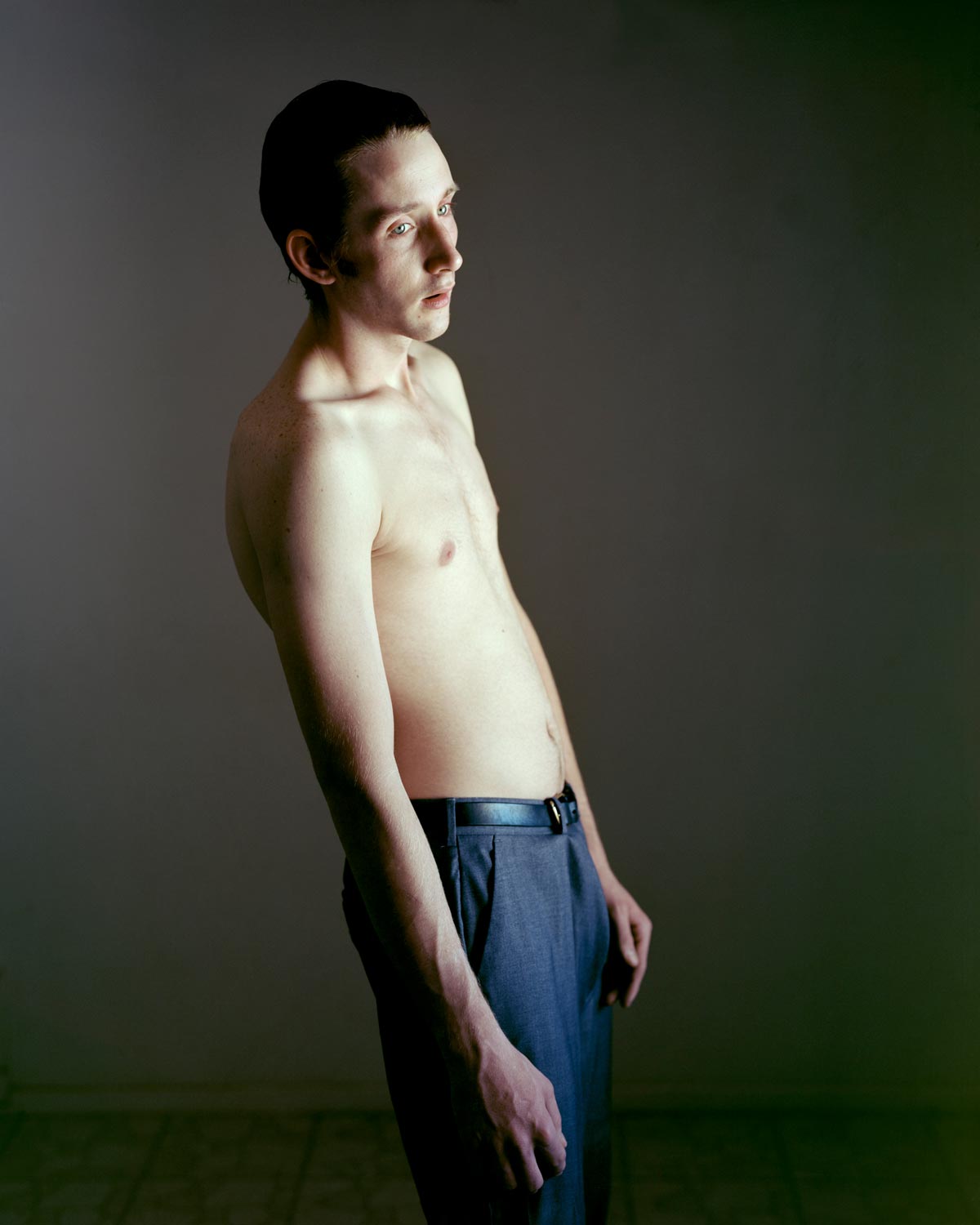

Before the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th 1945, and another on Nagasaki three days later, the American military conducted several tests to assess the destructive power of the bomb. The tests were carried out at a naval base in the deserts surrounding the Salton Sea, a saline lake in California. Today, the base is abandoned, yet 35 year-old Italian photographer Nicholas Albrecht was curious to explore whatever is left of it and of the tests that took place there, as well as any trace of how that unique story has influenced the people who live in the Salton Sea area. His series Artifacts from the Desert and the Impossible Search for the Atomic Device is an ongoing project which therefore mixes portraiture and landscape photography.

Hello Nicholas, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

It mostly started around the idea of getting to explore the lives of others. The camera was in a way an excuse to knock on a stranger’s door. As I continued to work with the medium and discover my relationship to it, I became more interested in the image as a thing on its own. The stranger was just a vehicle to create something unique. So in a way it became less about others, and more about the images themselves.

Please introduce us to Artifacts from the Desert and the Impossible Search for the Atomic Device.

A.F.D.I.S.A.D. is something I’ve been working on for the past three years. The work looks at the desert Salton Sea region in Southern California that was used to test the prototype for the Atomic Bomb in the early 1940s. I am interested in both the psychological landscape left behind by the tests and the physical evidence present in the area. The work is more about the desire to create something so destructive than it is about the resulting destruction. The impossibility of the search really refers to the difficulty of photographing something intangible.

How have you learned about the story of the atomic tests in the Salton Sea deserts, and what about it fascinated you in particular?

I lived in the Salton Sea area for a couple years in a motorhome while working on my first major body of work, One, No One and One Hundred Thousand. During my time there I learned a lot about the area and its history. I had also developed a very close relationship with the inhabitants and the desert landscape. I was interested in how peoples’ lives now unfold in a place that was used to create the ultimate death machine; the majority of the images are titled in a way to indicate their distance from the test site. So I’m looking at the relationship between the two—the people and the landscapes,—although so much time has passed that most of those who live there don’t even know that these tests took place.

What was your main intent in creating this series? What did you want your work to communicate?

I still have at least another trip to take down to the area before I can feel the work to be complete. It’s still missing some links between the portraits and the landscapes. The images jump from fact (naval base infrastructure) to staged portraits and manipulated landscapes. It can be a difficult connection to make and I need to create some more linking concepts for it to work. The project is meant to be more of a novel about land and destruction than a document of an event. It starts from fact and then tries to branch out conceptually.

Why did you shoot the portraits and landscape photographs of A.F.D.I.S.A.D. in black and white, with a few exceptions?

The use of black and white is mostly to reference the majority of the images from the 1940s that we have regarding the Atomic Bomb. It also seems to work really well for a more conceptual approach. Every photograph is removed from its subject at least once, but a black and white image is removed even more. The photograph becomes something of its own, in someway detached from what it depicts.

The color images are used when the color is either the main subject of that image (for instance the RGB gels in the desert) or a strong element in the mood of the photograph. The use of 8×10 inch film is really to embrace the difficulty to photograph. The stress the film has to go through in the desert heat and the room for variables while processing the photographs in my darkroom adds another dimension to the work, it somehow calls its physical attributes into play.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on A.F.D.I.S.A.D.?

Nothing specific to the concept of the project; maybe more the idea of intervention in the photographic scene. Treating the landscape as a sculpture and then photographing it seemed a very appropriate way to be thinking about photography. I also could never get some work by Ellsworth Kelly out of my mind: the simplicity and power really stuck with me for quite some time.

How do you hope viewers react to A.F.D.I.S.A.D., ideally?

It would be great if the viewers were engaged by the work. Ideally it would generate some form of curiosity that would push them to try to understand the work. This work is meant to be viewed in its physical form, where the object-photograph is important. Standing in a room with the images would certainly be the best way to experience it.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

I think growing up relocating often with my family pushed me to look at culture in a certain way. I find that this ultimately fueled my interest in the medium. I can’t say that art was a big part of my life up until university. I generally preferred the streets to anything else. My brother, my Latin tutor from 9th grade, my grandmother, parents and the unbelievably backwards streets of Naples have most shaped the way I see things.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

The one that has had the biggest impact on me is Jeff Wall. Many of the traditional notions of what photography is have been abandoned by him, and yet I find his description of the image to be the most fascinating. I’ve always loved the great American landscape photographers and the idea of the road trip, portraits from small towns in Eastern Europe and more conceptual and provocative work like Viviane Sassen or Michael Lundgren. It’s really hard to answer this as the list would go on forever. I find most genres of photography to be appealing.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Land. Adaptability. Lies.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025