Jakob Ganslmeier Portrays Former Neo-Nazis Who Are Removing Their Nazi-Inspired Tattoos

We’re featuring this project as one of FotoRoom’s favorite entries to the recently closed foto forum x FotoRoomOPEN call. (Did you know? We’re currently accepting submissions to a new FotoRoomOPEN edition: enter your work for a chance of being represented by all-female agency ACN.

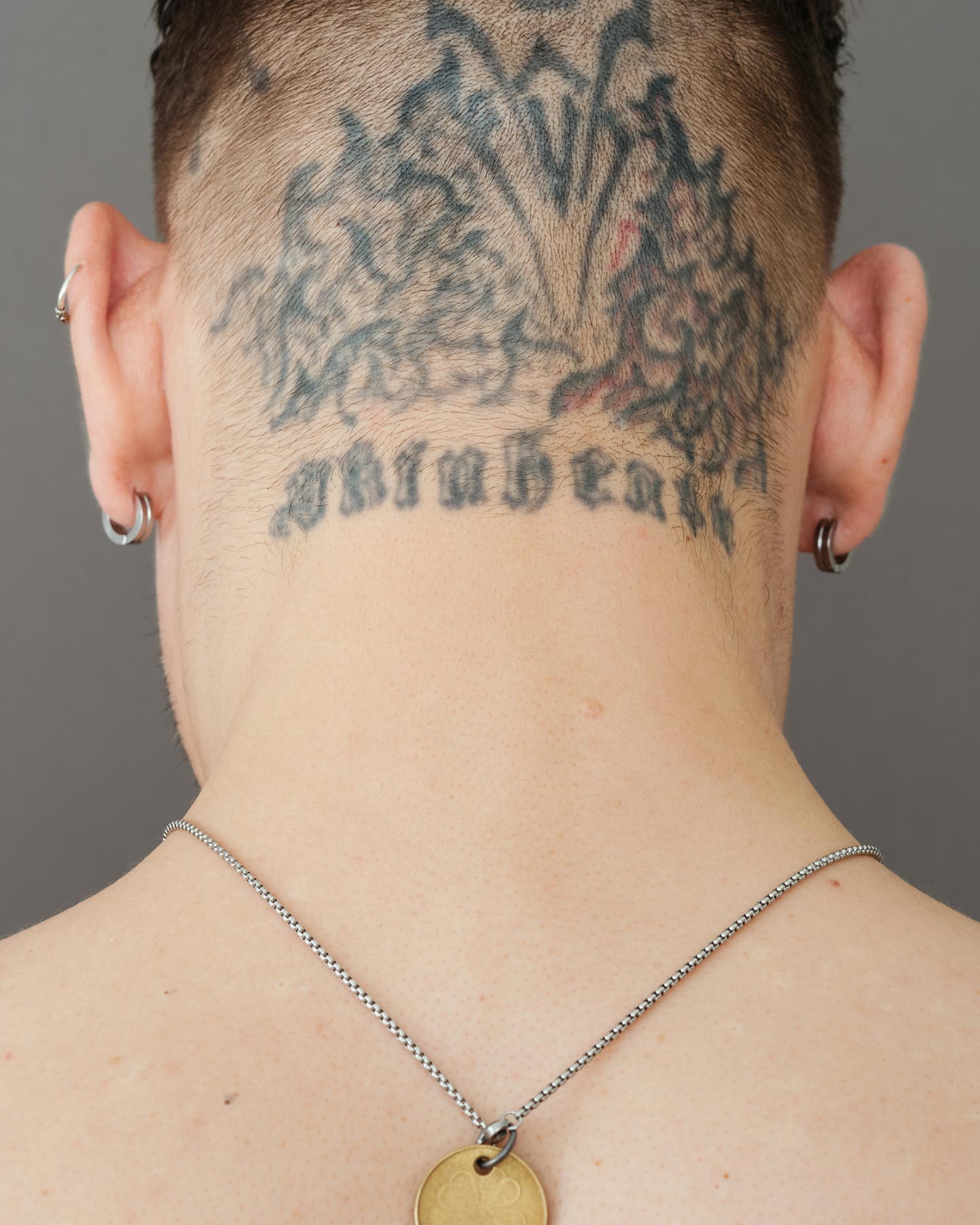

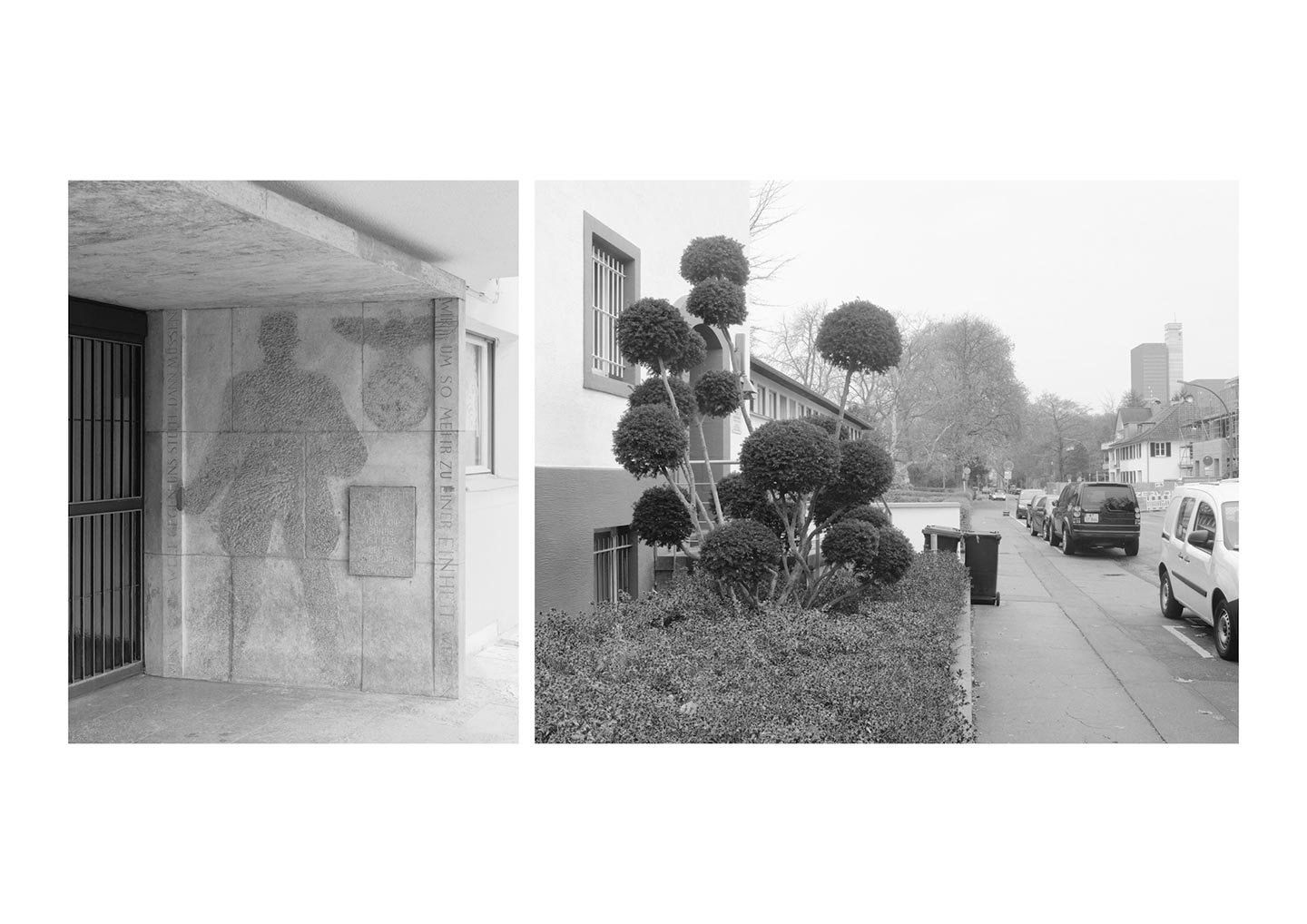

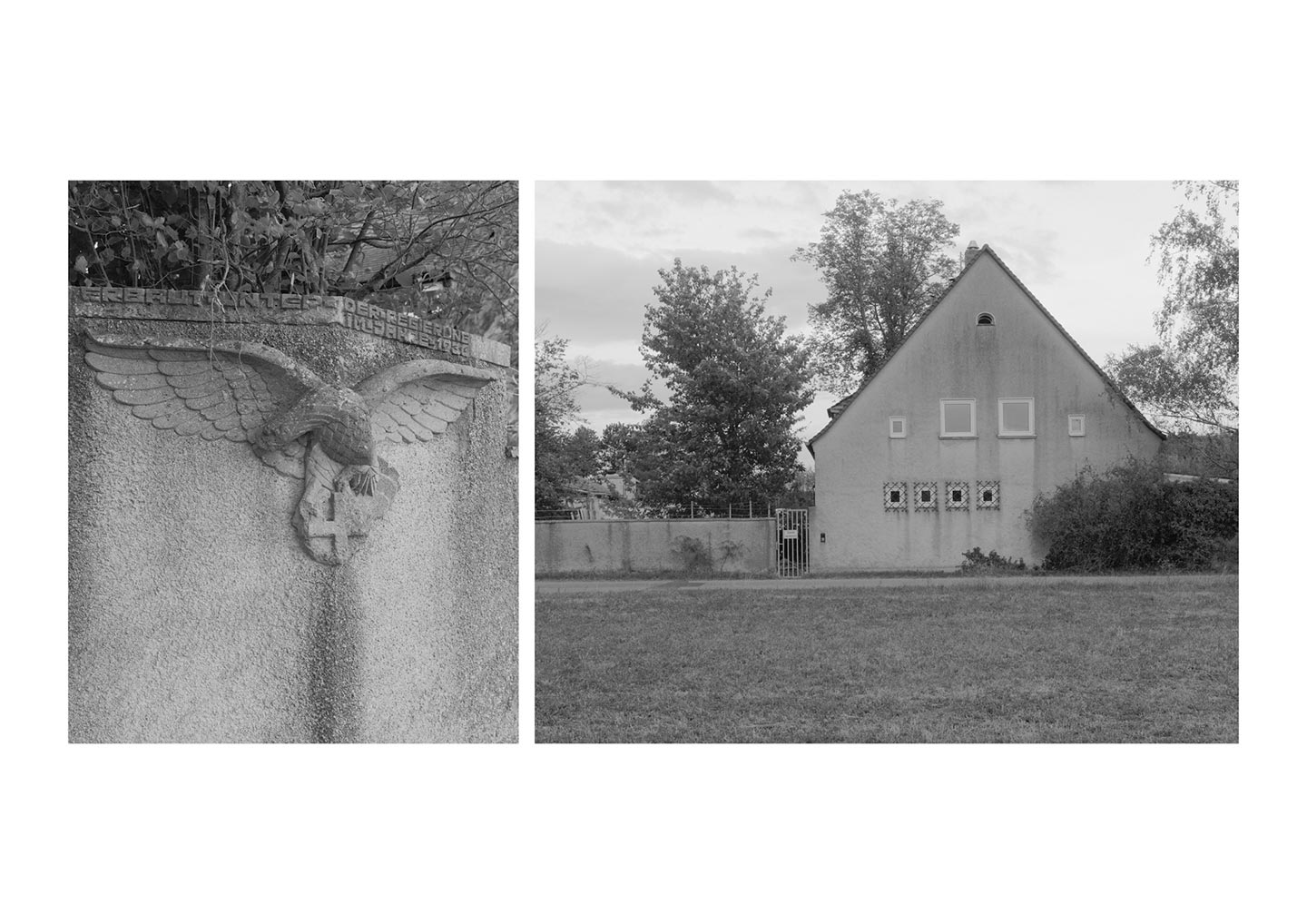

Haut, Stein (German for ‘skin, stone’) by 29 year-old German photographer Jakob Ganslmeier is a series of photographs in two parts: one group of images are black and white photos of Nazi symbols that can still be found across German cities; the other group consists of color staged portraits of former neo-Nazis who are removing Nazi-inspired tattoos from their bodies as part of their process to move away from the neo-Nazi subculture. The work also includes transcript interviews to the photographed individuals.

Jakob’s project stems from a collaboration with Exit-Deutschland, “a non-profit organization that helps neo-Nazis leave the far-right scene” he explains. “Through Exit-Deutschland I have been able to work with eight former neo-Nazis of both genders who well represent the wide range of individuals you can find within far-right extremist groups. Among the subjects I photographed there are a former high-ranking operative for NPD, Germany’s far-right, ultra-nationalist party; a former leading figure of the Identitarian Movement; a former Kameradschaftsführer (a paramilitary rank originating in the Hitler Youth); as well as a former member of the Autonomous Nationalists. They live in Germany, Austria and Switzerland.”

In the interviews, these individuals explained Jakob that turning their back on the far-right movements they belonged to is not easy: “International networking between German’s far-right extremist groups and similar groups based in other European countries is a common practice—my subjects used these networks in various ways or were involved in activities promoted within the framework of such collaborations. They would work with members of the European groups to organize music concerts, memorial marches, seminars, demonstrations, meetings for groups and individuals to exchange views, etc. The process of moving away from all this is inherently complex and different for each individual: the experience of discontinuity and the problems related to the (re)construction of an identity following the break-away changes from person to person, based on the individual’s former role and the time they spent in the Nazi subculture with their former peers.”

As he kept taking portraits of his subjects and documenting the removal of their tattoos, Jakob started wondering how the denazification of Nazi symbols works in general. That’s how he began shooting the second group of images in Haut, Stein: “The black and white photographs show historical Nazi symbols embedded in urban architecture and public spaces. Despite the so-called denazification, many of these symbols are still visible and therefore part of the everyday life in cities and in the countryside. I’ve conceived these photos as diptychs: one image closes up on the symbol itself, while the other is a sort of establishing shot to provide some context on where the photographed symbol is found (and to suggest the strange feeling of finding Nazi emblems in regular public spaces). The core of the analogy between these images and the portraits is that the tattoos my subjects are removing are a sign of commitment to the Nazi ideology just like the symbols disseminated in the urban environment were for Nazi Germany.“

Of the many sources of inspiration he had in mind while working on Haut, Stein, Jakob mentions the works of Michael Schmidt, Ulrich Wüst, Katharina Bosse and Ludwig Rauch as the most important ones. Ideally, Jakob hopes his series inspires viewers “to question how we—not only Germans but populations of other countries with a different history as well—deal with our past, how far away this past really is, and how neo-right movements try to trivialize it.”

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024