Entrance to Our Valley — Jenia Fridlyand Shares Poetic Photos of Family Life on Her Farm

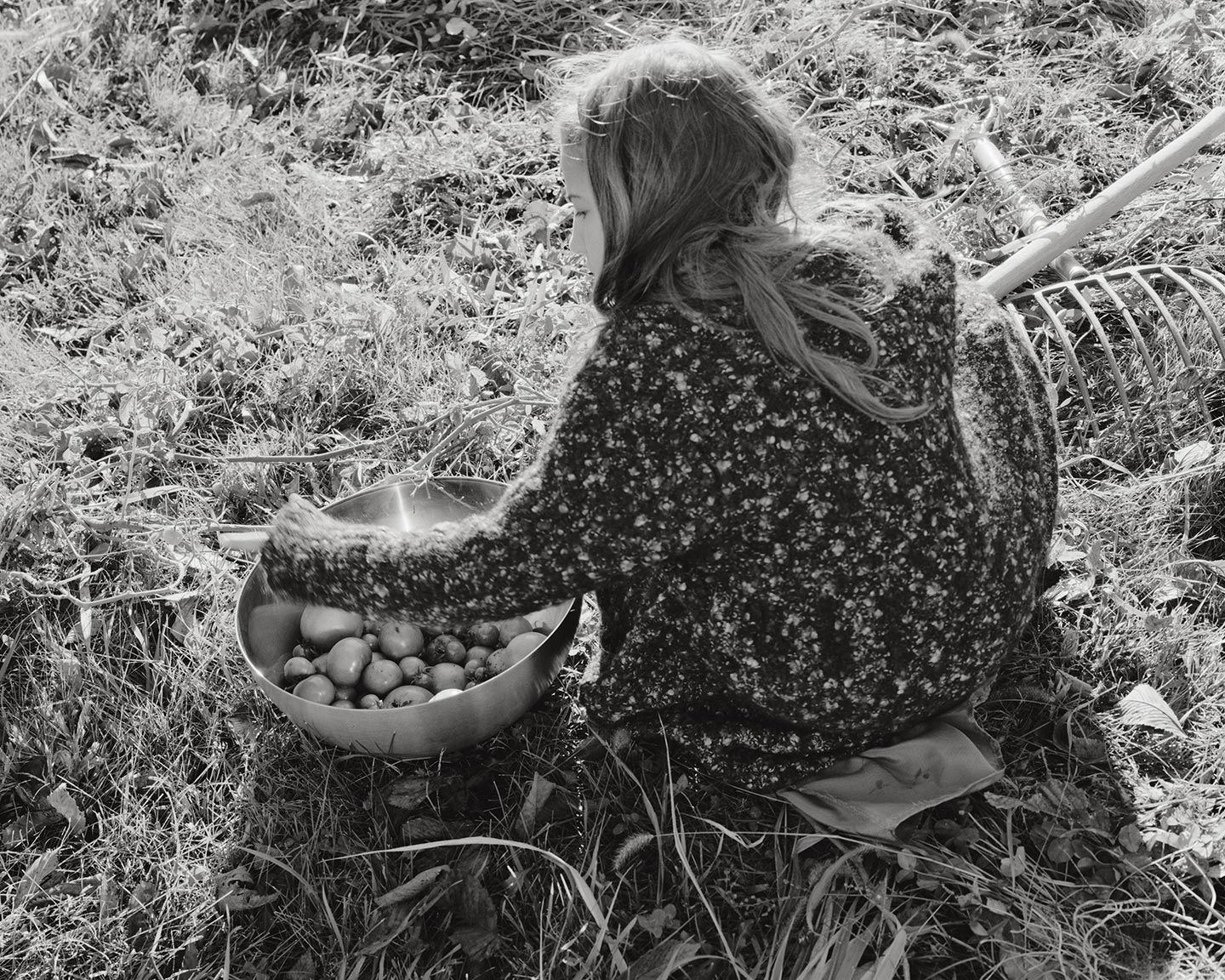

Entrance to Our Valley by Jenia Fridlyand is a series of beautiful black and white images, shot on film, inspired by The Cherry Orchard, the last play by the famed 19th century Russian playwright Anton Chekhov. “It’s an absolute masterpiece” Jenia comments, “and like any masterpiece, it is “about” many things at the same time, but the plot is fairly simple: at the turn of the 20th century, a Russian aristocratic family is compelled, by financial hardship, to auction off their cherry orchard. It ends up in the hands of a bourgeois merchant, son of the family’s former serf, who, by the end of the play, is cutting the trees to develop the land into cottage plots. I reread the play recently, and would highly recommend doing that—or seeing a production—to anyone not familiar with it.”

The images of Entrance to Our Valley (which are available as a book—buy your copy) were shot at the 200-acre farm in the Hudson River Valley that Jenia and her husband bought for them and their entire family. “There was a moment when I realized that the story of Entrance to Our Valley is the story of Chekov’s The Cherry Orchard transported to another time, reversed left to right and flipped upside down on the ground glass of my view camera. A century later, on the other side of the globe, descendants of Eastern European Jews, who were not allowed to own land in Imperial Russia, take the place of hereditary Russian aristocrats, and are attempting to create what the characters in the play lost: an inhabited piece of land, a home, an identity. However, what seems more germane to me than the inversion of the plot is the lack of apparent reasoning behind both the destruction and the creation. It is as if in both stories the protagonists seek to define, through their actions, what it means to be Russian—a very tenuous concept in relation to what the country is now, or to what it was over 100 years ago, when Chekhov wrote the play.”

“I can almost say that this body of work was a byproduct of a process that had to do with my relationship to the farm itself” Jenia explains. “Our main motivation for buying it was to establish a multi-generational home: for our parents, who are now living more than five thousand miles from the place of their birth; for my husband and I, both first-generation immigrants; and for our children, so they could have the privilege of coming back to a place where they grew up. Both my husband and I are third generation Moscovites—our grandparents came to Moscow from Ukraine as students in the early years of the Soviet Union—so we grew up and always lived in large cities, with no experience of rural existence or farming; and, as I mentioned, there was no history of land ownership in our families going back centuries. It was quite confounding to find ourselves on, and in charge of, over 200 acres of land, in the middle of the Hudson River Valley, whose own rich history begins in the pre-Columbian era. Photographing there, intensely, was my way of getting to know the place and making it my own.”

Jenia started shooting for Entrance to Our Valley at the same time as she was learning to work with large format and black and white film. “The switch wasn’t easy after several years of using exclusively medium format color, but with time I began to reap the benefits of this particular medium. Especially helpful was the distance it provided, both formal (reversed image on the ground glass, removal of color) and physical (use of tripod, the dark cloth), which makes photographing in one’s immediate surroundings—and one’s immediate family—that much more tenable. Because, to make the images, I also had to distance myself from all the contextual and narrative considerations mentioned above.”

Sources of inspiration for Entrance to Our Valley ranged “from paintings by Andrew Wyeth to Paddy Summerfield’s lyrical photographic project Mother and Father, but I think the single most influential reference was Michael Schmidt’s Natur. I’ve looked at this book obsessively for a few months prior to beginning to the body of work, and later found myself subconsciously remaking some of the images.” Jenia tells FotoRoom that “I had my motivations to make the images, but I don’t necessarily think those particular motivations should be manifest in the resulting body of work. As long as the final group of images is coherent and viable, the viewer should be able to enter it and find their own meaning and connections. That said, I would like to mention one particularly heartwarming reaction. The first solo show of this work took place in Ukraine, where most of my ancestors come from. Quite a few people, of all different generations, came up to me to say the images remind them of their own childhood.”

Jenia has an educational background in science—both her parents are scientists as well. “I think I carried over from that domain the need to be actively constructing my understanding of the world. For me, photography is just another way to do that.” Before turning to photography, she was interested in literature, “but because I emigrated to the United States when I was 13 years old, my Russian never quite had a chance to mature, and English never quite became a native language. One of the most momentous epiphanies of my life was that photography, in book form, could be used in the same way language is used in fiction: to construct a self-sufficient world. So I would say that literature, and literary thinking, has impacted my practice no less than the visual arts.” Some of her favorite contemporary photographers are Robert Adams, John Gossage, Emmet Gowin, Gerry Johannsen, Susan Lipper and Mark Steinmetz, “to name just a few.” The last photobook she was greatly impressed by is Berlin in the Time of the Wall by John Gossage (“The complexity of this masterpiece just keeps giving on every level, from individual images to the book object“).

Jenia’s three words for photography are:

Love. Lust. Language.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025