74 Prisons, 10 Years — A Long Look at the Lives of South America’s Encerrados

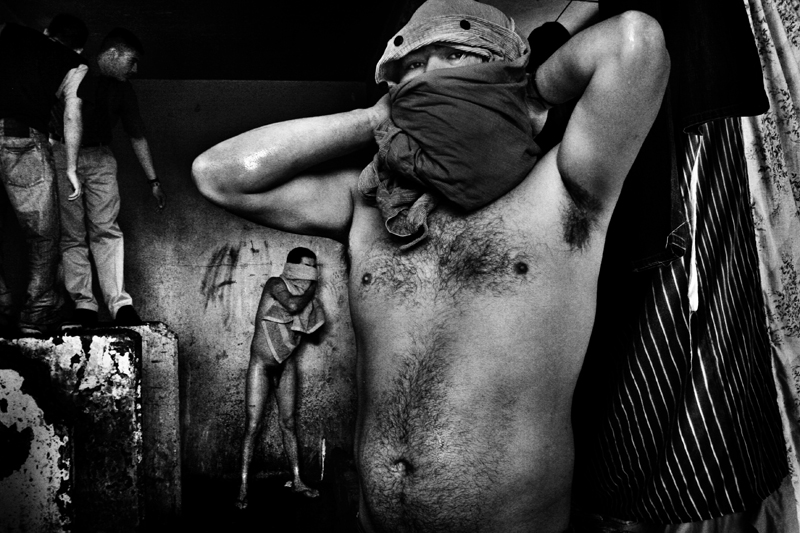

Encerrados is the result of an impressive effort in photojournalism which brought Italian photojournalist Valerio Bispuri into 74 South-American prisons over a span of no less than 10 years.

Encerrados was awarded, among others, the 1st prize in the Contemporary Issues category of last year’s Sony World Photography Awards; now Valerio is looking to make a photobook of Encerrados through this crowdfunding campaign.

Read our interview with Valerio Bispuri to find out more about the dramatic situation of prisons in South America.

Hello Valerio, thank you for this interview. Tell us about how the idea for Encerrados came about: why did you decide to document South America’s prisons, and when did you understand it would have taken years to complete the project?

I made Encerrados because I’d been wanting to document South America for a long time, and I was looking for a theme that would allow me to explore in great depth the core of South America. Prisons were the chance to observe the individual countries while gathering an overview of the entire continent.

It was clear to me that Encerrados would have required a great time commitment when I realized that permissions to photograph in the prison were going to take months to obtain. In a few cases I’ve had to wait for years.

Which was the first prison you visited? Do you remember your impressions?

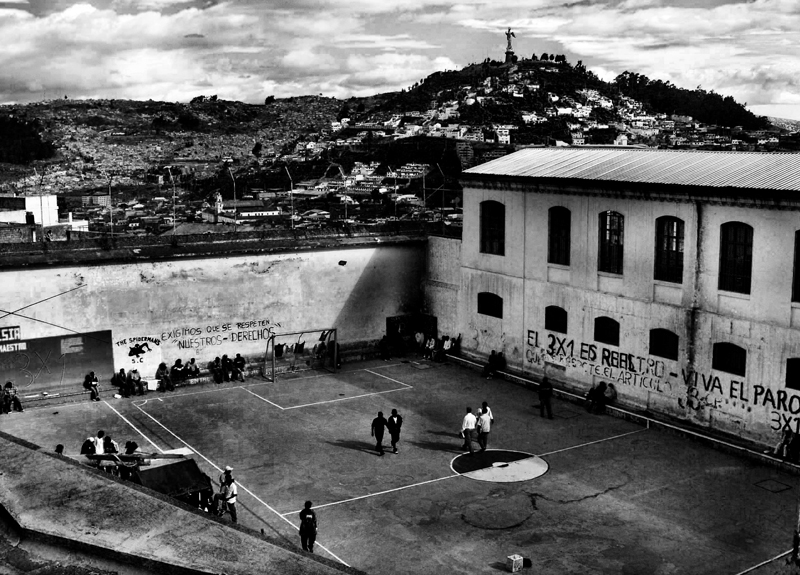

The first prison I set foot into was in Quito, Ecuador’s capital city, and it really happened fortuitously. I was in the city for another assignment; but while at dinner with several people, I met a writer who had just published an essay about Ecuador’s new prison system. He suggested that I photograph one of Quito’s prisons – he knew how to let me in. It was a devastating experience. I wasn’t prepared to what I would have seen: I still remember the inmates yelling and throwing urine bags at me because they didn’t want to be photographed.

In Encerrados‘ statement, you say that there are groups of inmates in control of the prisons. In one particular instance, the prison’s director had to seek permission to let you take pictures from some of the prisoners. How much structured is the power of these groups?

Well, there are prisons in countries like Venezuela or Chile where prisoners possess weapons and have a certain degree of power. But the episode of the director asking for “permission” to the inmates only happened in the Bangu 2 institution in Rio de Janeiro. More generally, to talk about groups in full control of the prisons would be to go too far.

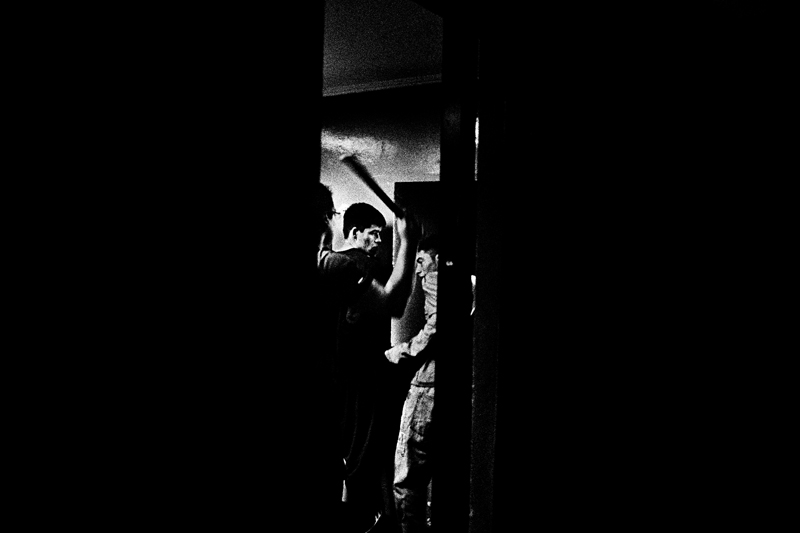

Did you ever stumble upon episodes of violence? And were you ever the subject of aggression?

I’ve never seen violence among the inmates, but aggressive events and rebellions certainly occur. The suicide rate across the entire South America, however, is close to zero. On the other hand, I have personally been the victim of several aggressions: having been into 74 prisons, it would be strange otherwise. Once, a few inmates prepared an infected blood shot to hit me with; another time, they put a knife behind my neck.

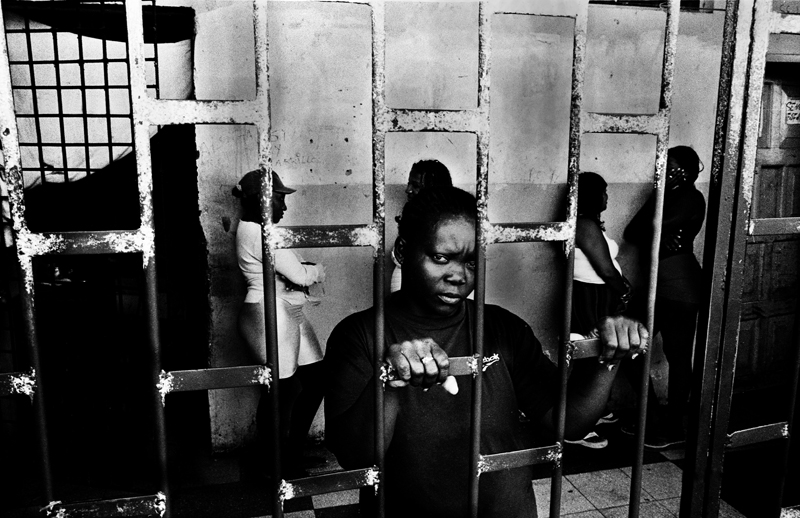

Is there violence in female prisons too?

There certainly is anger in female prisons as well, which sometimes turns into violent attacks. Moreover, in most prisons, female inmates are denied the “intimate visit”, that is the possibility to have sexual intercourse with their husband or partner, which is instead granted to those male inmates who behave properly.

You say that prisons are the mirror of a country. What countries are those in South America?

Prisons reflect the good and bad of the social, cultural and economic milieu of the countries they’re found in. When incarcerated, the inmates experience an initial phase of anger and frustration, sadness and fear; but then they adjust to their new condition, and try to bring inside the prison their usual habits. In Argentina, for example, before the cells are shut down in the late afternoons, the prisoners gather and have mate (a typically Argentinian and Uruguayan beverage).

You must have heard the personal stories of many prisoners. Is there any that impressed you particularly?

Yes, I’ve heard so many stories and so powerful,but I’d rather not share any: it wouldn’t be fair towards all the others who had terrible lives.

If you were given the chance to do one thing to improve the conditions of the inmates in South America’s prisons, what most urgent measure would you take?

We actually already did something: following an exhibition of my images, held in Buenos Aires in 2009, in collaboration with Amnesty Internacional and Argentina’s government we had the pavilion n. 5 in Mendoza’s prison closed. Life conditions there were tragic.

Without doubt, the biggest problem of South America’s prison system is that the institutions are overcrowded, so the first thing to do would be to build new structures. I also think it would be helpful to offer the inmates the possibility to engage in a number of activities: prison shouldn’t be just about the punishment.

10 years and 74 prisons later, what did you learn about humanity that you didn’t know before?

That the human being has hidden resources, and holds tight onto life not to surrender.

Pick one of the photographs from Encerrados and share with us something we can’t see in the picture.

The image that opens Encerrados best represents the world of men and women incarcerated. Faces and hands appear from within a pavilion; the eyes are full with anger, disappointment, hope, fear and all those feelings that prisons’ inmates have.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2024