“Chaotic, dirty, dusty, colorful” – Vincent Delbrouck Shows Us His Nepal

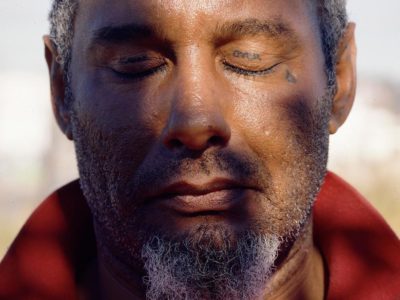

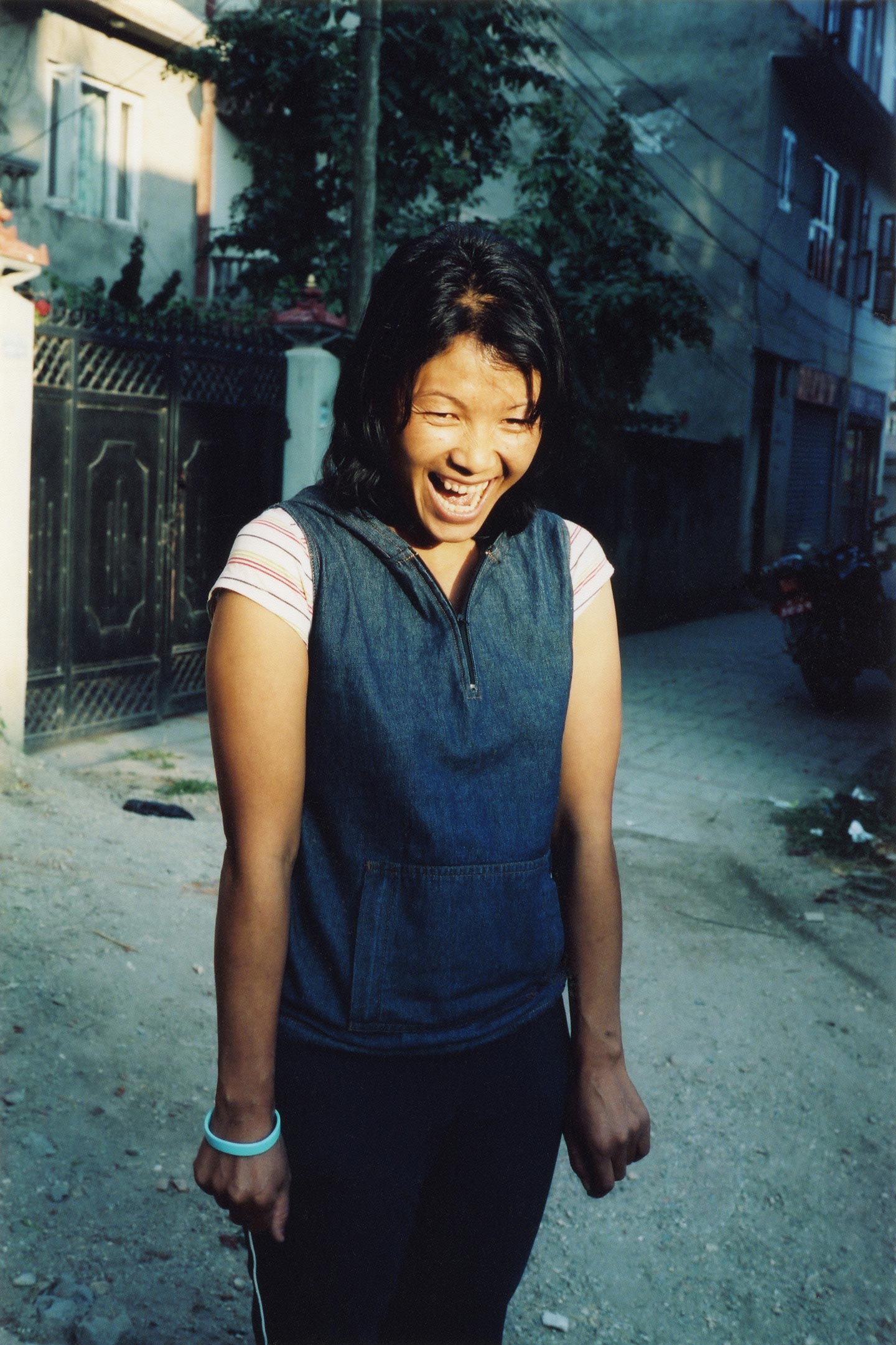

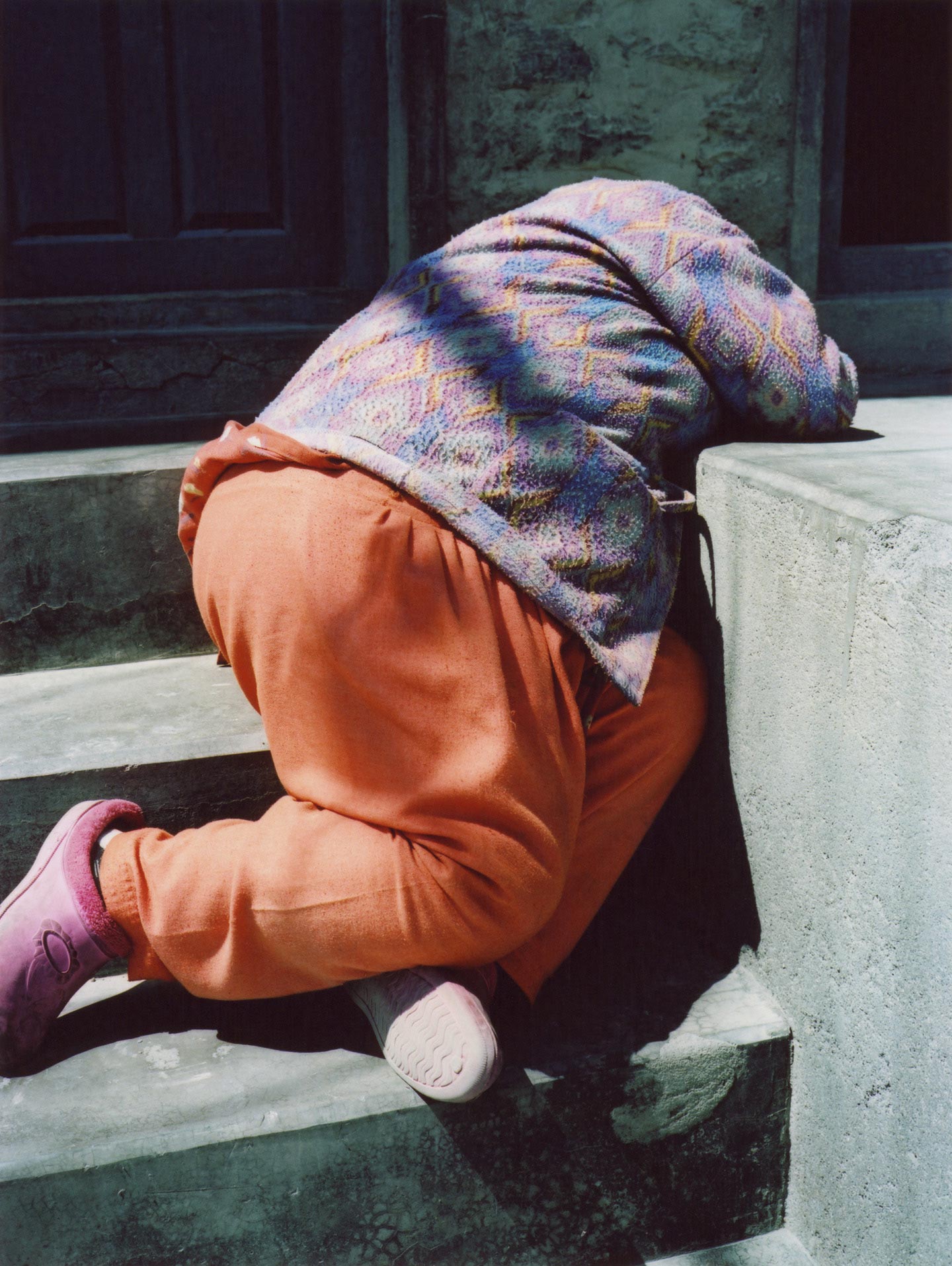

40 year-old Belgian photographer Vincent Delbrouck speaks about Dzogchen, a self-published book of photographs made in Nepal and titled after a tradition of Tibetan Buddhist teachings.

The Dzogchen photobook is available to buy from Vincent’s own online shop.

Hello Vincent, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

The sweet confrontation with the matter or the luminous substance of the “real and dirty” world, and the extraction of an imaginary world from it. Being completely inside the landscape of the natural body of energy; losing myself in this creative challenge and finding happiness in it, despite the doubts, the sometimes difficult relations with people, the post-analysis, the addiction to perfectionism and hypersensitivity.

Painting new portraits (of women) with photography is always fabulous; walking alone and finding good still life in a territory which becomes my nest too, and living with the warm and tropical light is amazing – breathing the air saturated with a fruity odor of kerosene and salt form the sea… Just there, after a good day of intense work with photography, capturing some kind of flow. That’s it. A colorful story. Touching bodies. The rest is just intellectual bullshit and illusion and lack of confidence.

Dzogchen is the last in a trilogy of books of photos made in Nepal and the Himalayan region. What brought you there in the first place, and when?

It was in 2007, my wife and I came to visit my brother-in-law in Kathmandu. He has been living there for years, teaching the Tibetan language in a center for Himalayan Studies and Buddhism in the capital city of Nepal. After this trip we decided to go back to Nepal with our son and considered the idea of living there for a year. And that’s what we finally did in 2009-2010. It was good not to be brought to this place by just a photo project, but by life itself. I love that. Living and working and mixing everything. Pure improvisation, with of course ideas and small plans in my head but more like dreams and desires, certainly not like a well established structure or scenario. For me, photography is improvisation and a love affair with some places in the world.

What do you find so unique about Nepal that compelled you to work in that land for so long?

Nepal is chaotic, dirty or dusty, colorful, breathing life at every minute, touching my skin and my heart, adopting me with pure kindness. Mustang, around the Annapurna, is the most beautiful and intimate territory I’ve ever found in my life. It is nature, it is organic like a river in the mountains or like a strong wind. Not something easy, not something arranged with a taste of superficial design or like an aseptic space with landscape seen just as an external landscape (viewed from outside) and hyper technological cities. It’s something from inside the intestines, and emerging like Cuba for me. Not something exotic, no no no; it is home. And the the nest of my adoptive spirituality with Tibetan Buddhism (and Bön) and Wilderness.

Your pictures typically capture small, mundane objects and details of the everyday life. How would you describe your photography? When are you happy with a photograph you made?

Maybe it is a bridge or a secret door from the little objects or the characters of an intimate story to the imagination at the other side. Somewhere there is this color, this form, this beautiful illusion in details and faces and animals and plants with no hierarchy, and I am happy when I can find my rhizome or ancient personal roots inside this territory I create, connecting with strong energies and finding myself not so anxious anymore at the end. Photography is a treatment against the void, and it is connected with literature and painting or collages. You can find deep love in it – really strong love and curiosity. I put the elements at the center of my photographs and I shoot with the intuition of disappearing into the forms.

Did you have any specific reference or source(s) of inspiration in mind while working on Dzogchen?

Certainly a lot: novels, short stories, texts from the Dharma, “bad” photobooks from the 1960s, poetry, D.H. Lawrence, Carl Jung, Raymond Carver, old stuff I made before, “bricolage”, nature and walking.

In the Dzogchen photobook the pictures are often laid over other pictures or sheets of colored paper, adding a special energy to the work. Can you talk about the main ideas behind the book’s design?

Last year I was planning to have a book with only full bleed pictures on the right pages and blank pages on the left. Then I had to postpone the making of the book, but in the meanwhile I made new pictures in Nepal in autumn. When I came back to the book itself at the end of the following spring, I started sticking the images as collages on some paper I had. I prepared several spreads like this with no written scenario, just doing it over and over again, improvising with the intuitive idea of what it would become at the end. Dense and colorful. At the end of June I worked at home with Philipe Koeune, my friend and graphic designer, on new collages on paper: we spent together four crazy and very intense days, in the countryside. At the end of the session we spread all we had on the floor, giving life to sequences in my living room, most of the time with a rapid feeling of connections between some pages. No slow thinking. Then I worked on the rhythm of the book for another month.

There is no main pre-conceived idea behind the book design; it’s just the product of millions of connections made by my brain I suppose, a process of time and handicraft and simple visions. It’s strange but that’s how it is. The narrative is like a puzzle of fragments, which has to be coming to a conscious life. (Almost) nothing is made on the computer – this is all handmade to work faster and experiment.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Maybe literature. The dirty realism of a Charles Bukowski or a PJ Gutierrez; the short stories of Raymond Carver or John Cheever. Magnum photographers at the beginning of my career at the end of the 90’. The energy of the Caribbean and the Himalayas. Women (feminine energy). Nature and silence. Havana. The collages of Robert Frank. A lot of movies too. The paintings of Peter Doig. A long term photo work I made on/with old demented women at the beginning of the 21st century. Some indie fashion magazines (years ago). Practicing shiatsu massages. Meditation. American photography of the 1970s. My chaotic and fast and hypersensitive intestinal brain. Writing. Desire. Walking. Frieda Khalo. Sea, sex and sun. Birds!

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

I love the work of Gregory Halpern, Wolfgang Tillmans, Stephen Gill, Paul Graham, Max Pinckers, Raymond Meeks, Paul Gaffney, Lieko Shiga, Seba Kurtis, Viviane Sassen, Arno Nollen, etc.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Paper. Constellations. Red.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in October 2024