Jason Koxvold’s Photobook ‘Calle Tredici Martiri’ Was Inspired by His Grandfather’s World War II Diaries

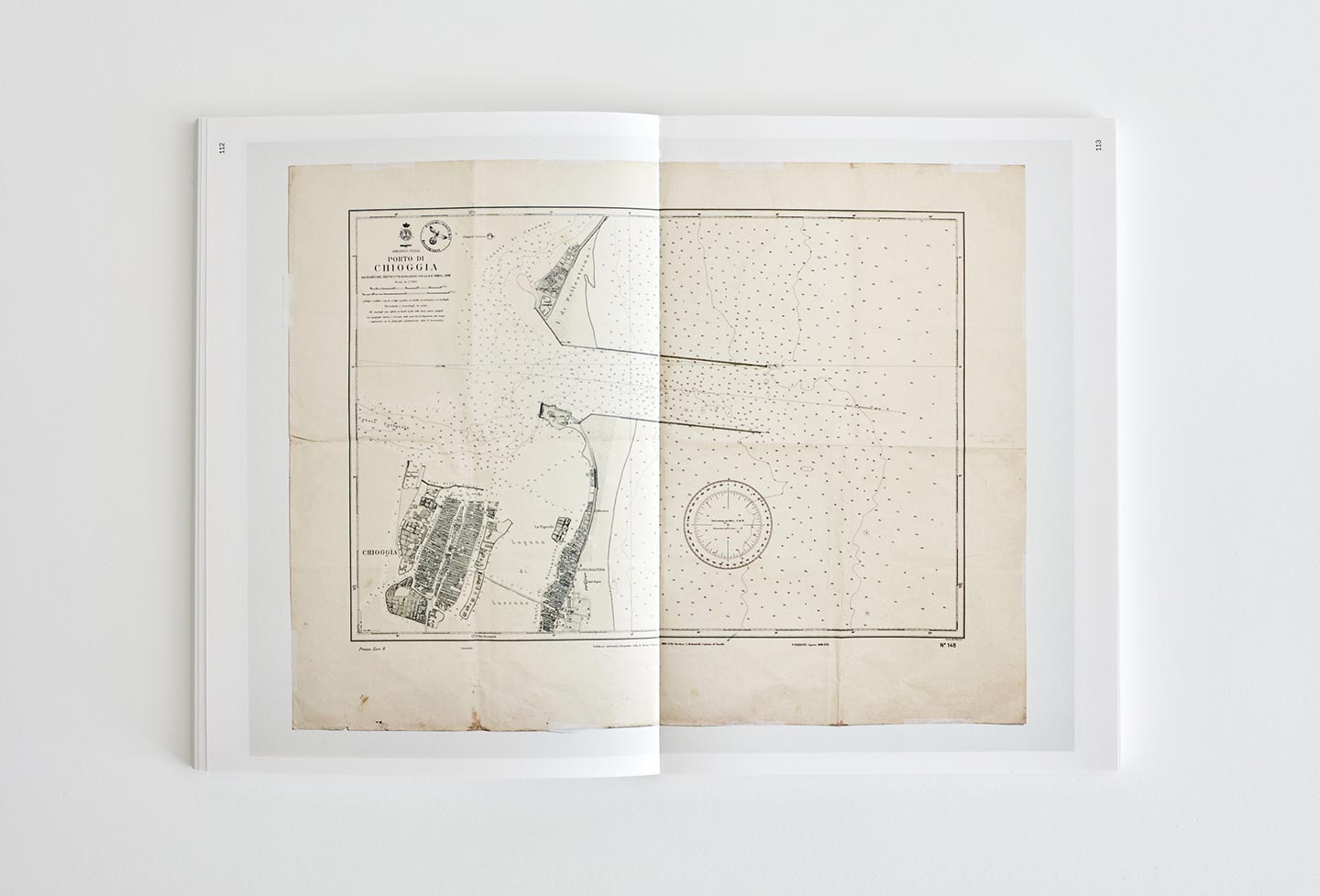

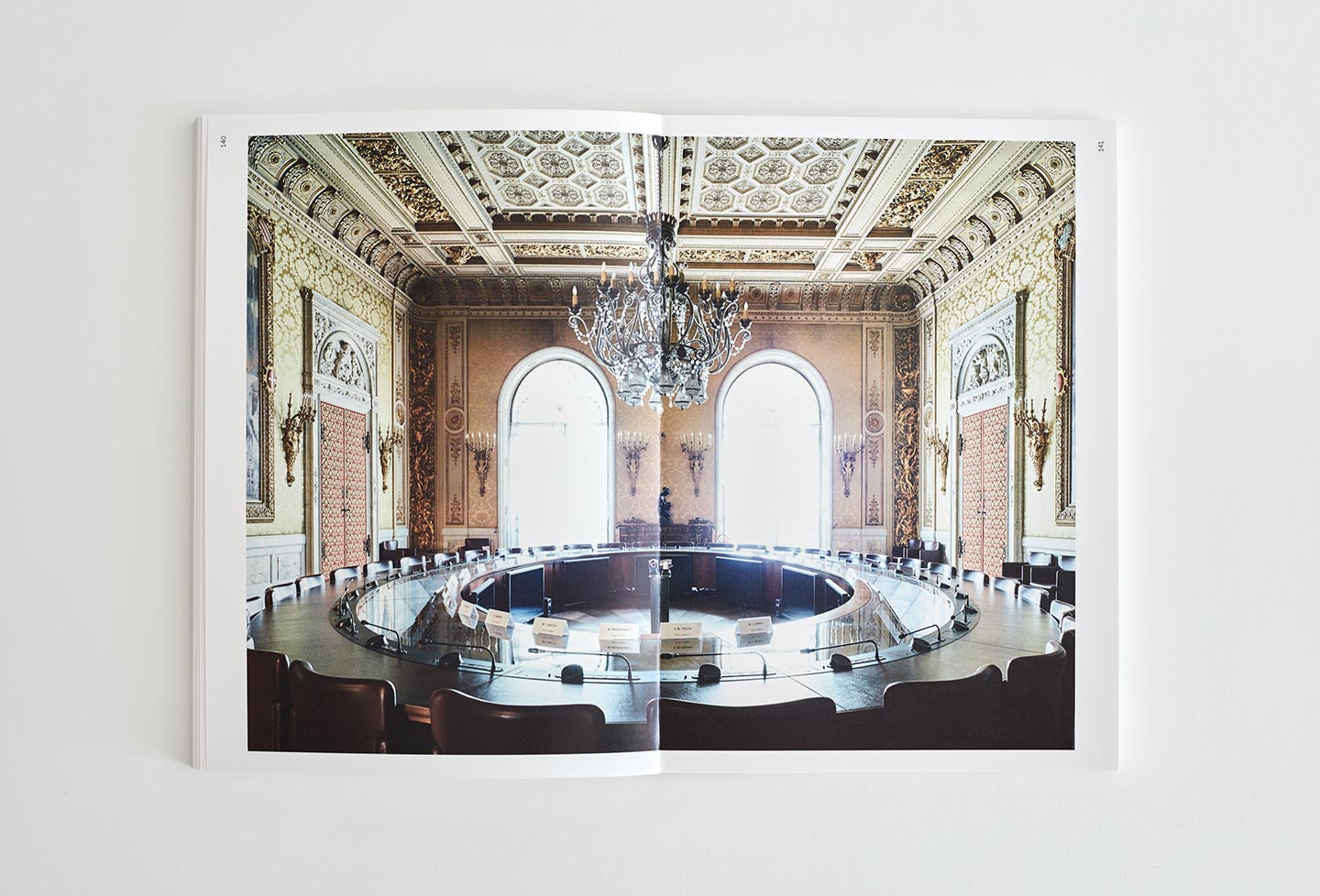

Calle Tredici Martiri by photographer Jason Koxvold is a photobook recently released by Gnomic Book (buy your copy), the publishing house founded by Jason himself in 2015 that has been putting out a series of very interesting titles. Calle Tredici Martiri is translated as “Alley of the Thirteen Martyrs”, and it’s the name of a narrow alley in the city of Venice, Italy, nearby the historical Palazzo Ca’ Giustinian: in 1944, a resistance group of Italian partisans fighting against the Fascists introduced and set off a bomb in the palace, which today is home to La Biennale di Venezia, but back then was the headquarters of the local Fascist authorities and their German allies. 13 people were killed in the explosion; a few days later, the Fascists retaliated by executing 13 men who had been previously imprisoned for being considered antifascists. The head of the partisan group that organized the attack at Palazzo Ca’ Giustinian was Aldo Varisco, Jason Koxvold’s grandfather.

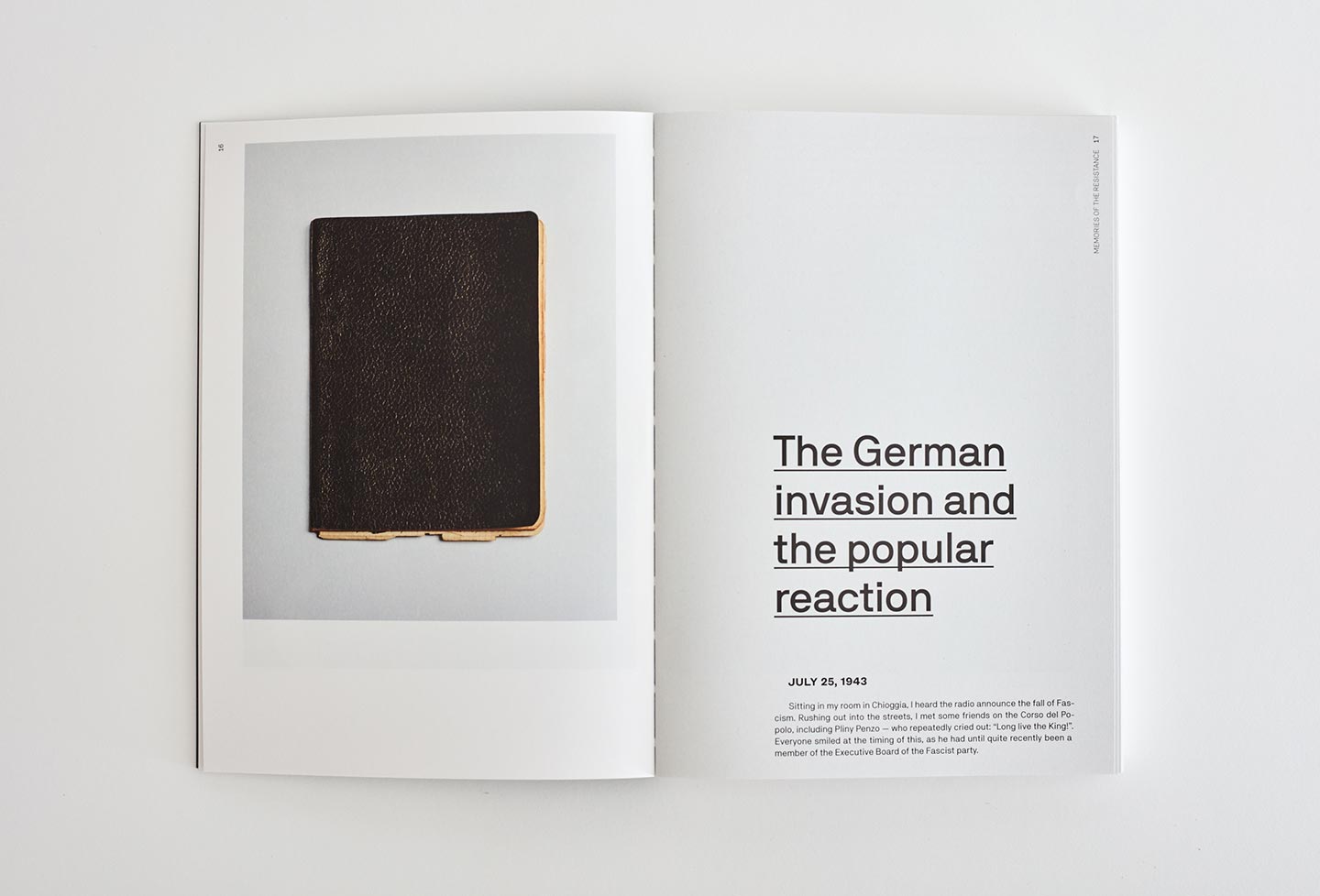

Varisco kept written logs of his activities as a partisan. “The first time I saw the diaries was probably in 2012” Jason remembers. “My mother had run them through Google Translate but they were very difficult to read: between his very formal writing style and some formatting difficulties, it was impossible to get a sense of the arc of the story. I started seriously editing them in 2016, a few pages at a time, and what I found was that the story unfolded very slowly, in a way that changed my perception of it over the length of two years.”

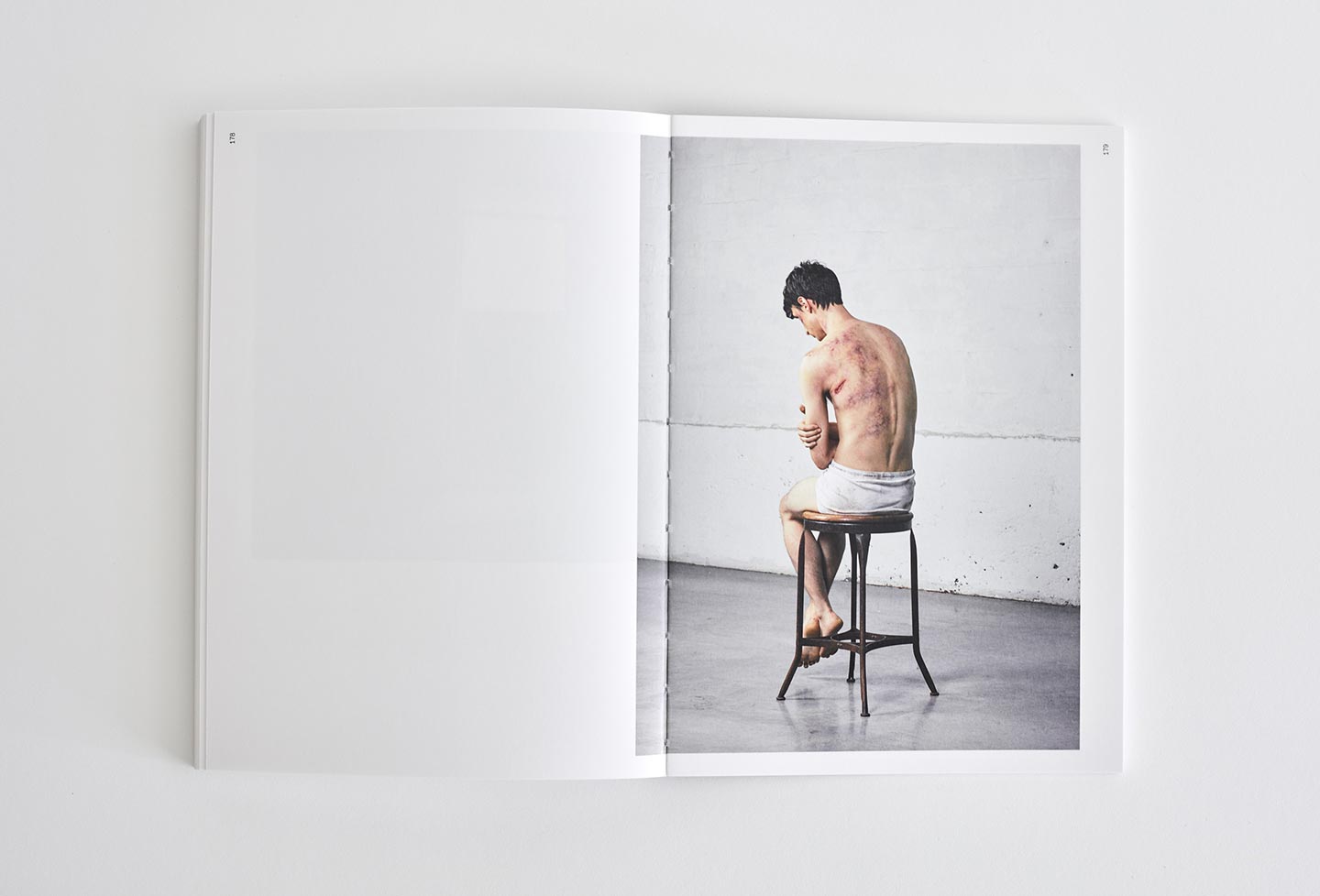

Some pages from Jason’s grandfather’s diaries are published in the Calle Tredici Martiri photobook: “Initially this project was not going to be for public release. Believe it or not, I envisioned it as a family cookbook: recipes handed down through the family, juxtaposed with stories of the Resistance. But as the text revealed itself I started to see parallels with our present-day political situation, and started to understand just how severely he had been tortured, and as a result I treated the project far more seriously. I was particularly interested in the notion that, in today’s parlance, my grandfather was what we would call a terrorist: he indiscriminately threw phosphorus grenades at German soldiers; he oversaw the bombing of a building that killed 13; he planned targeted assassinations, all in defense of his homeland; and he was tortured by people who collaborated with the invaders. This situation is mirrored almost exactly in what we witness today in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the conflicts that have spilled out of those theaters.”

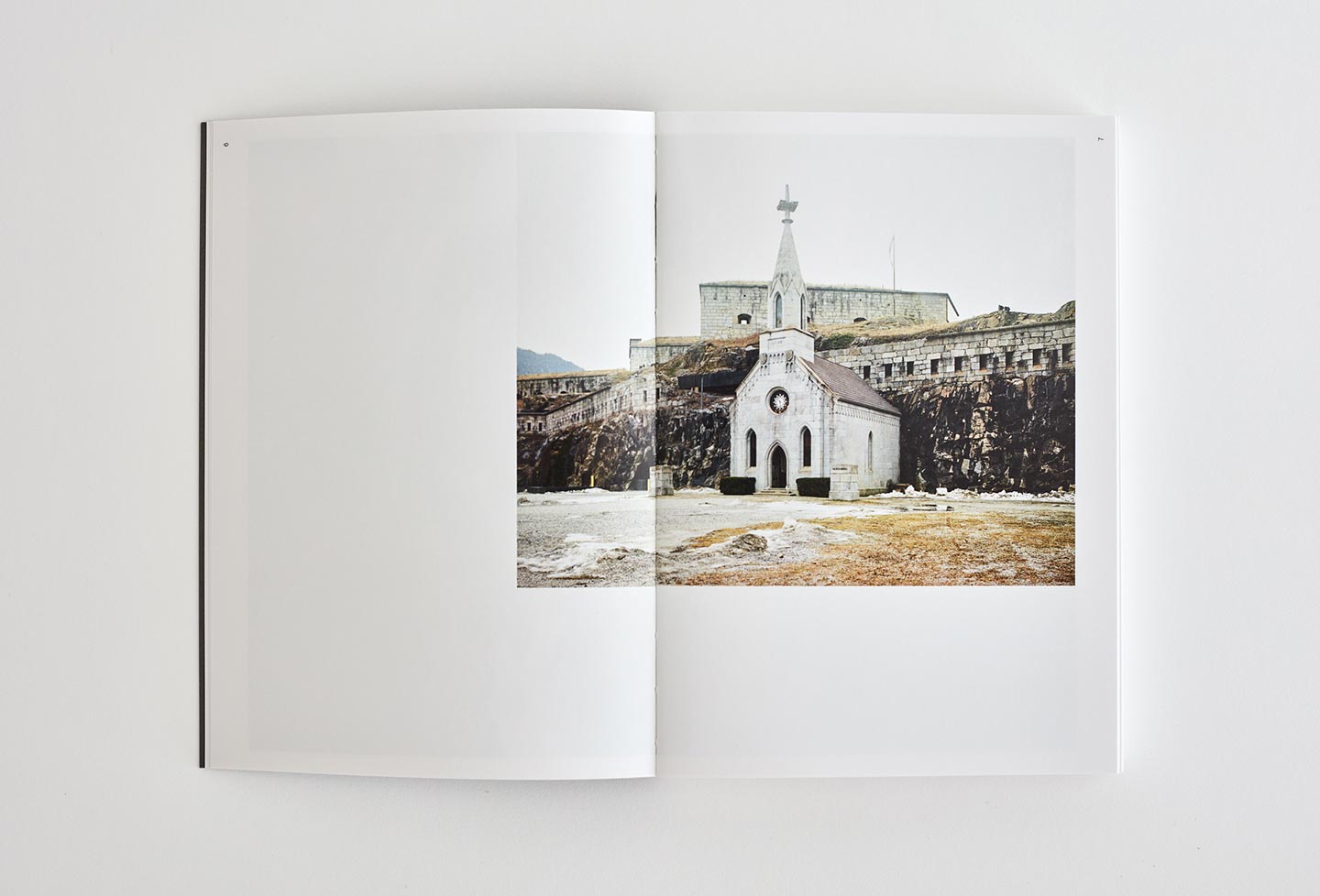

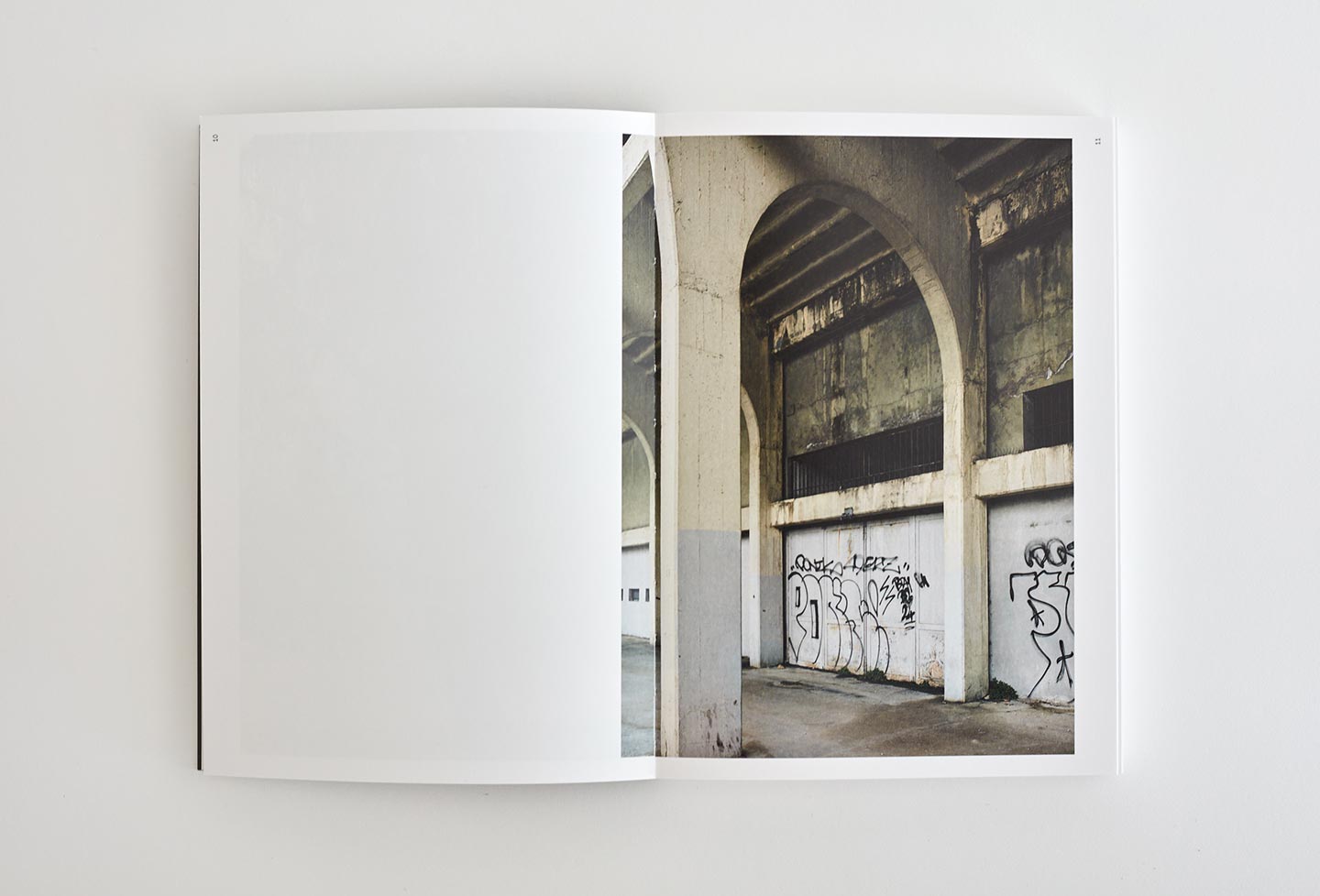

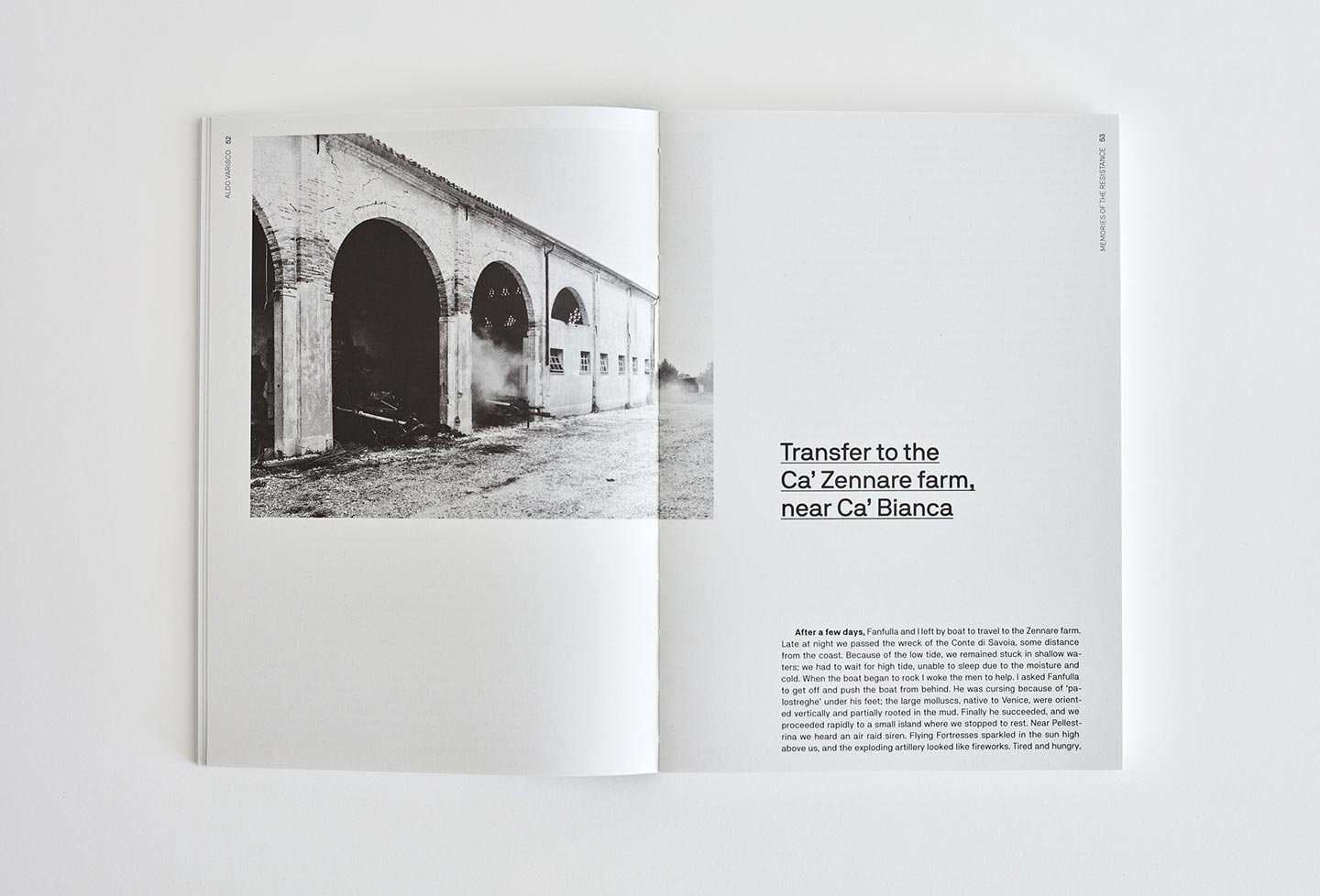

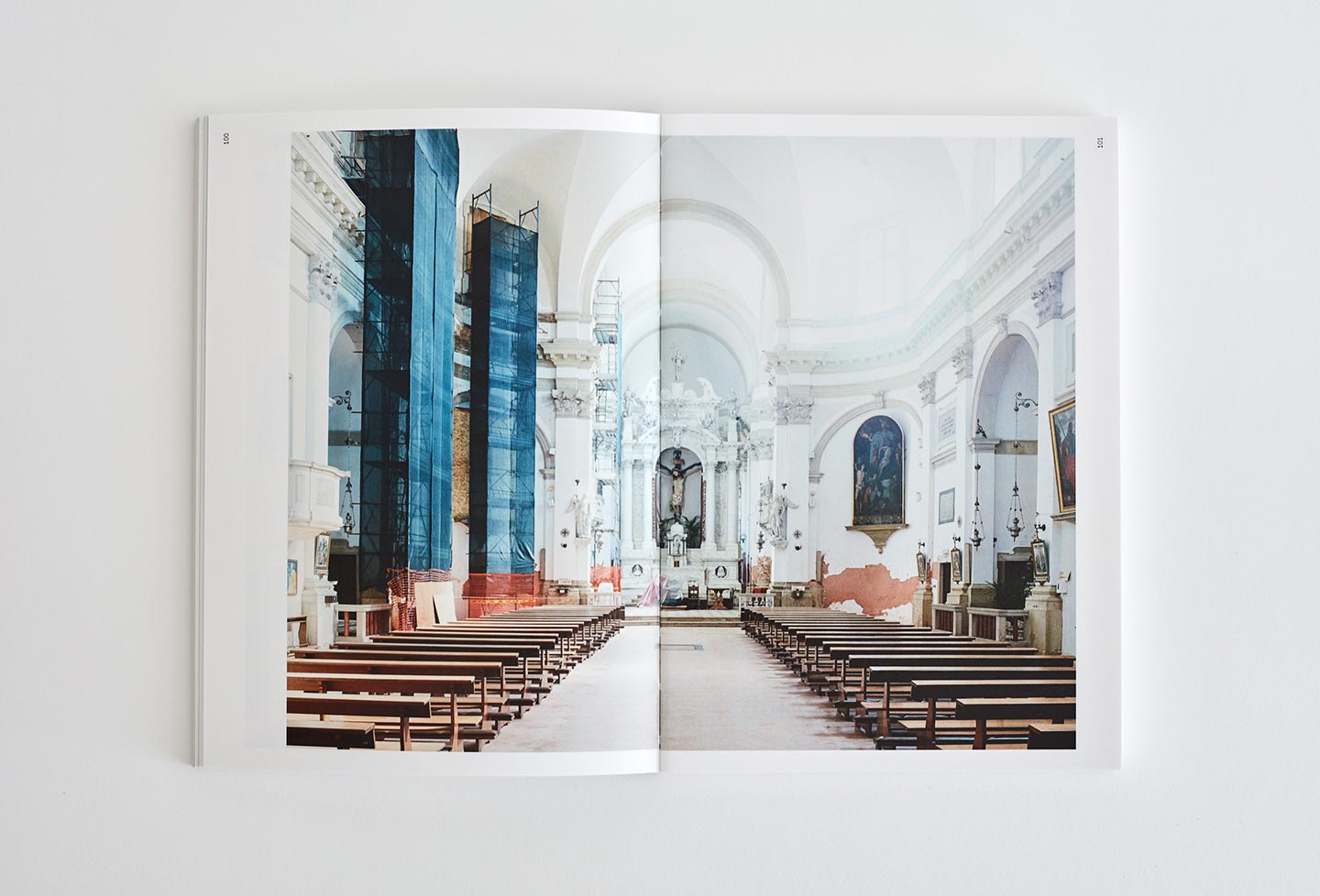

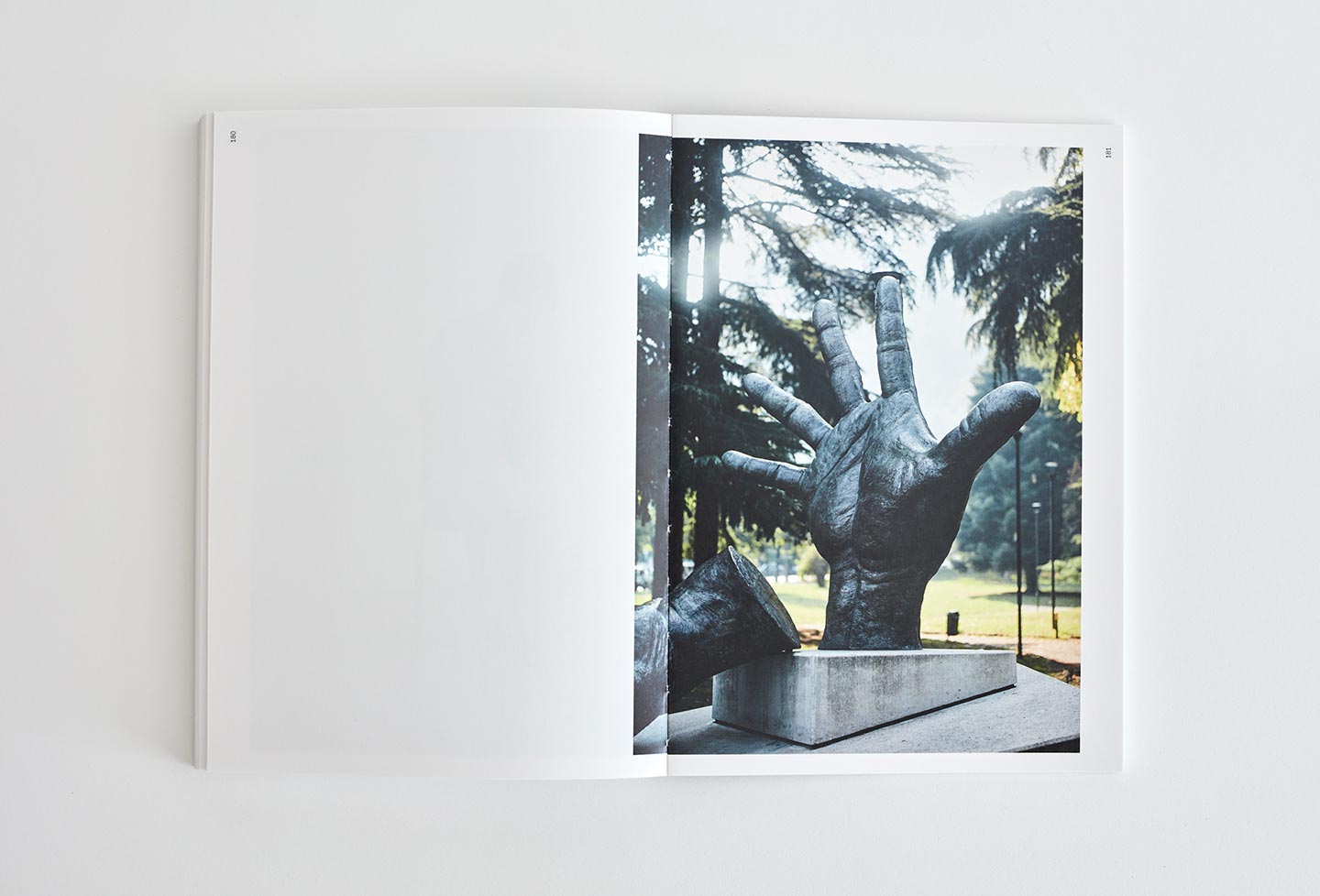

Varisco’s writings published in the first part of Calle Tredici Martiri are accompanied by archival photographs, while the second part of the book presents pictures shot by Jason himself, who visited the places described by his grandfather in his diaries to create a “fictionalized photographic reinterpretation” of his memoirs. “Because I’m not able to photograph a man being tortured, for example, I have to reinterpret it in a way that acknowledges the artifice” Jason explains. “Or, I made photographs at a training camp operated by a former Italian special forces infantryman, but I leave it to the viewer to decide where his political loyalties lie. By sequencing the photographs in a particular way I’m able to create false narratives, in the same way as Varisco’s text observed false narratives being seeded in WWII, and the same way as we see false narratives being developed even today as the U.S. makes the case to invade Iran, just as they did in Iraq.”

Jason’s decision to keep his grandfather’s memoirs separate from his original photographs was made with the intention to “draw parallels between the text and the images, but not in a literal way. It demands a lot of the reader, to engage with the text in its entirety before the photographs can be readily unpacked. It’s the same reason why the images are not captioned: in images which are quiet, it suggests a history of violence; in images which are overt, it leaves renders the story opaque.”

Besides being about the stories narrated in his grandfather’s diaries, Calle Tredici Martiri also explores “the impossibility of the photographic truth,” Jason says: “There is a great deal of misunderstanding of the nature of the photograph: what it does, what it says, how it operates, how it can be used. The notion of photographic truth is held up as sacrosanct by organizations that champion photojournalism. But during the embed programs of the Iraq and Afghanistan invasions, photographers would travel with infantry units; their access was predicated on the assumption that they would share images that would support the war effort. Without physically modifying the image, the image is modified before the photographer even operates the shutter. Opposition to these wars is impossible: the news media does not cover it. When the band The Dixie Chicks spoke out about the Iraq war in 2003 they were blacklisted and their careers were cut short. We torture, and outsource the torture of “enemy combatants”, sometimes to death, but those “enemies” turn out to have been misidentified; and yet the people directly involved in these torture programs are not held accountable, but rather promoted to, say, Director of the CIA. Donald Trump continues to advocate for torture, because he believes “it works”, and very little disagreement is heard from the public.”

“These wars are not fought on moral grounds, but financial” he continues. “The Lockheeds and the Raytheons issue glowing earnings reports when the Syrian war starts to heat up. At the last count that I’m aware of, the U.S. was dropping 26,000 bombs in one year on the Middle East and Afghanistan; we literally could not build bombs fast enough. When Trump launched a cruise missile strike on a mostly empty Syrian airfield, at a cost of some $82,600,000, the news media called it “beautiful” and stated that “this was the day that Donald Trump became President.” When we view a photograph, we bring several factors to bear in its interpretation: our political leanings, our cultural beliefs, our lived experience. As such, in a state where the public has been manipulated so extensively and for so long, even if it were possible to create an image that was somehow pure, even if it were objectively presented, its interpretation would still be altered by the person viewing it.”

Buy your copy of Calle Tredici Martiri via the Gnomic Book website.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025