Beyond Laponia — Christian Liliendhal Brings Us to the «Last Wilderness of Europe»

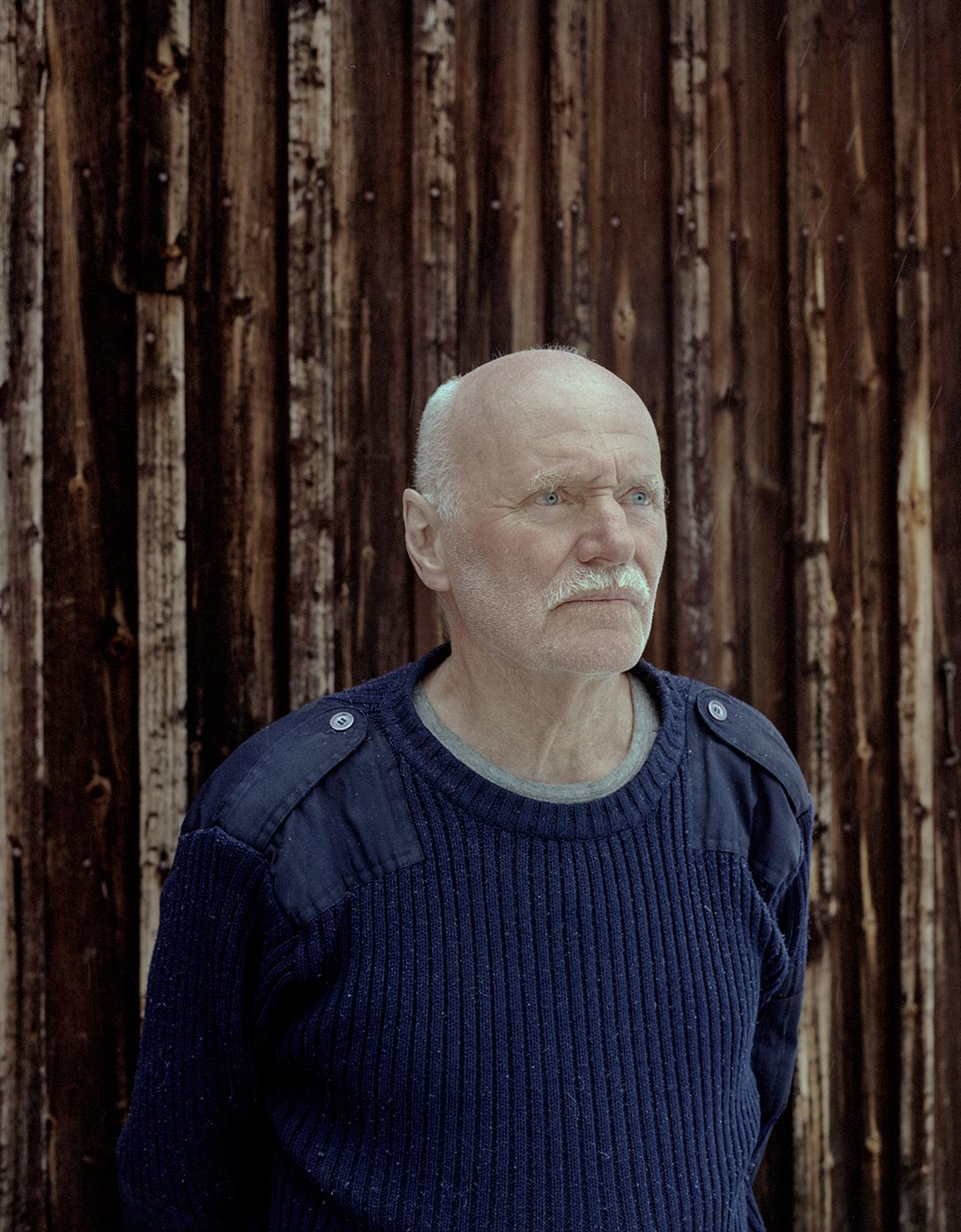

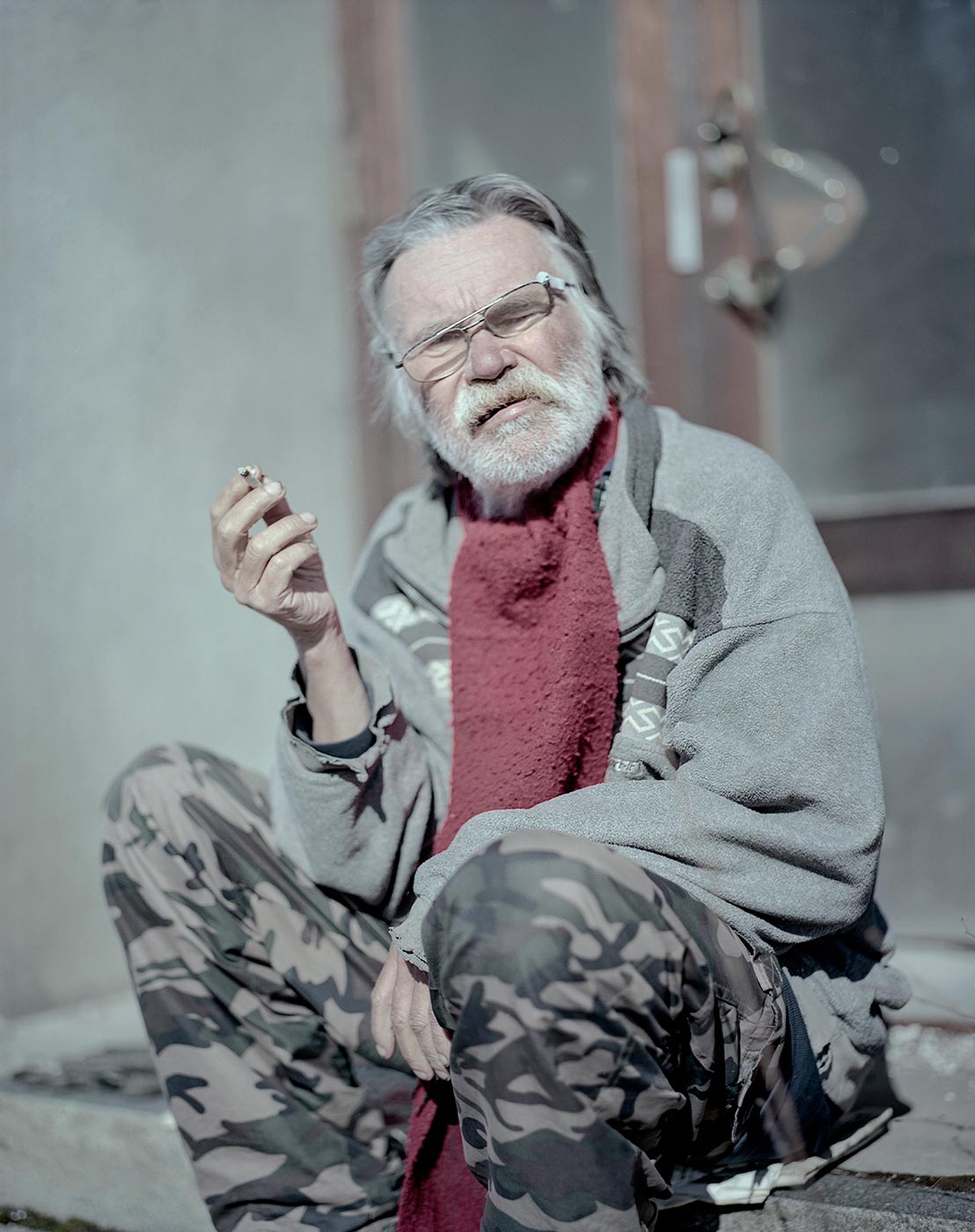

In this interview, 42 year-old Danish photographer Christian Liliendhal discusses Beyond Laponia, a subjective reportage that captures daily life in the Swedish part of the remote Lapland region in a series of landscape photographs and staged portraits of the people that live in the area.

Hello Christian, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I’m mostly into photojournalism and documentary photography. But I don’t look at only one specific area of photography. I think you can use a specific camera—digital or analog—and different kinds of film in relation to what you want to tell and what your pictures should express. Seeing other photographers’ work, and finding out how they shot that picture or project, opens up your own creativity and makes you want to challenge yourself, how you work as a photographer, and maybe also what kind of stories you want to tell.

Beyond Laponia is my very first, big project, shot on medium format film.

Please introduce us to Beyond Laponia.

My project Beyond Laponia is about the daily life of the Swedish population that lives in the Swedish part of Lapland. Many photographers, documentarists and journalists are drawn to the nature and people of that remote area, but they usually focus on the Sami population. I’ve been to Lapland a couple of times before starting my project, and I was very attracted to the Swedish people because they remind me of my own people, the Danes; yet again, they are so different. Also, the group I’ve chosen to document is very underrepresented in the media.

What inspired you to travel to and make work in the Swedish Lapland?

I took my first trip there in 1993 I think, when I was 19 years old. I went hiking in the area around the cities of Kiruna and Abisko, in my last year as a boy scout. 10 years later I climbed the Kebnekaise mountain for the first time. Both times I went by train directly to Kiruna, with no stops on the way. In 2014, I returned with my girlfriend and 1 year-old son, this time in our VW camper. We drove from Copenhagen all the way up through Sweden, to Kiruna and Abisko. Though it was a family summer vacation, I brought my Pentax67 and a bag of Kodak Portra film.

2014 was a great summer in Scandinavia. The scenery was amazing, the sun barely went down, young people hung out at the lakes, driving around in their EPA-tractors and listening to loud Eurodance… I realized that the pictures I would make could become my final thesis for the Danish school of media and journalism.

How would you describe the Swedish Lapland and the people that inhabit it? What does life look like in such a remote location?

If you live in a big city, you’re typically raised to think big—to study for a long time so you can get a good job and make a lot of money. Here, it seemed more important to enjoy life and be with good friends and family. People have time to meet and chat, without having to make an appointment days in advance. Initially, I was afraid that the locals would be more closed and wouldn’t want to talk to strangers or participate in my photo project for that matter; but that wasn’t the case. On my first day in the town of Jokkmokk I went to the tourist office and told them about my project. I didn’t have any contacts before getting there, but on that day alone I made my first three sources.

Like in many other parts of the world, you can come across many different people; but all of them—or at least all the people I met—love nature. Nature is such a big part of their environment that it’s also a huge part of what they are. Up there, it’s the humans who adapt to nature, and not the other way around. They use it differently: some use it for sports, like snowmobile and skiing, others for hunting and fishing. Generally, people experience the nature much more, and do things like picking up berries or stuffing big fridges with the meat and fish they get for themselves. It’s like going back 100 years, when you had to stock food for the winter.

If you like nature—for more than just a walk in the woods with your family—the landscapes of the Swedish Lapland will blow you away. It’s hard to describe, but that region has a very special vibe, smell and sound. You can drive for hours without seeing a single person or car. I have many times heard about that place as «the last wilderness of Europe», with some comparing it to Alaska.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to the work? What did you want your images to capture in particular?

Like I said, I chose to take my van because the distances up there are so big. This means that I always had a place to sleep and no limits as to where I could go. Driving also brought me further into the nature and the feeling that I was looking for. What I wasn’t quite aware of was that temperatures would drop to minus 8 degrees at night. But there is nothing a cup of coffee, a cigarette, Swedish cinnamon rolls and nature can’t cure in the morning.

As I had already been in the region with my Pentax67 and shot some single images, I knew that it was the right camera for the project. I wanted to emphasize the slow pace of life of the Swedish people by using a slow camera.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Beyond Laponia?

I had for a long time looked at Rob Hornstra’s work and seen his interviews on Picture Perfect or Vice, especially regarding his work about Sochi. Bryan Schutmatt’s Grays the Mountain Sends have also been a great inspiration to me. And such a big inspiration, that I brought a few prints, on the trip to Sweden, to be inspired every morning I woke up in my van.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

The most important influence were my classmates. The school environment, where you hang out and look at each other’s and other photographers’ work, is by far the best for the development of your own photography.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Rob Hornstra, Bryan Schutmaat, Joakim Eskildsen, Alec Soth, Krass Clement and many, many others.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Empathy. Trustworthy. Intimacy.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025