After Eisenhower — Jasmine Clark Explores the Impact of Military Culture on American Society

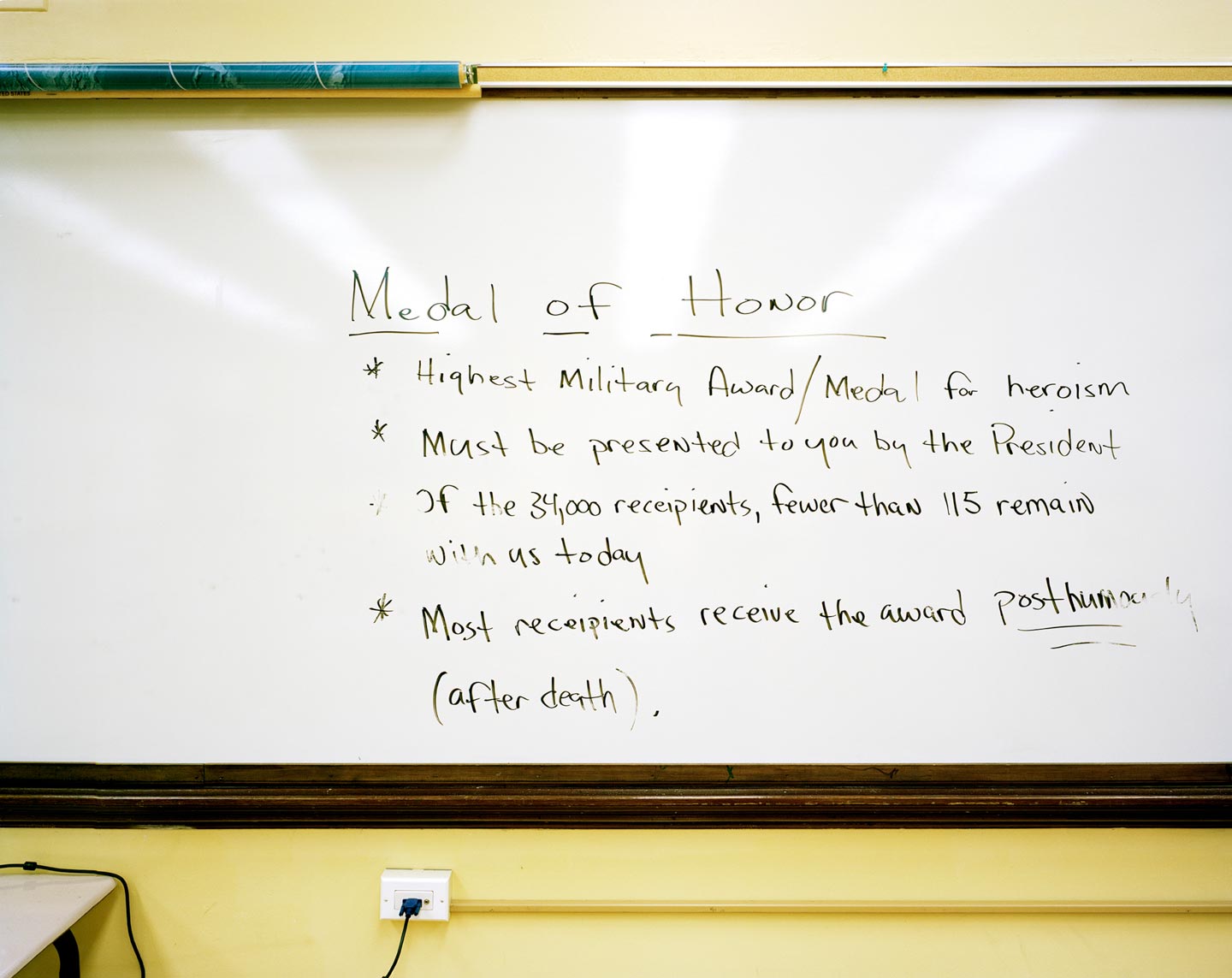

The life of small communities often comes to revolve around any major institution or business based in the area, mainly for the ability of such entities to offer jobs for the local population. 30 year-old American photographer Jasmine Clark was born in Twentynine Palms, California, a small city with about 25,000 inhabitants in the proximities of an American military base. In her conceptual photography series After Eisenhower, Jasmine examines the omnipresence of military symbols in the American culture and landscapes, starting from her native Twentynine Palms.

Hello Jasmine, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

A photograph’s function as a ‘document’ or ‘evidence’ to mark a particular time, place, event, and/or context—political or emotional, objective or subjective. I use photographs as devices to articulate when words fail, which happens often; to help convey something I can’t verbalize.

Please introduce us to After Eisenhower.

The photographs are influenced by my upbringing in a United States Marine Corps community in Twentynine Palms, California. Protection of others, protection of the flag, and patriotism are the ideals that stick with me. However, I question military and its role in American life and my own. American culture is inseparable from military and religious identity: the iconography of these elements, like the American flag or the cross, are ubiquitous in American society. The project comes from my curiosity and frustration due to the lack of questioning their inescapable presence. The series consists of photographs made in my hometown, Twentynine Palms, CA; in Chicago, IL; and in other small and medium cities located in the Southeast and Midwest. I plan to photograph in each state.

How do you think growing up in a place so highly charged with military messages influenced you?

For sure it dictated my visual language, my personal politics, my sense of self, and my perception of patriotism and American culture. It was something I passively thought about while growing up. I knew it was not necessarily common to grow up around tanks, etc., but it was my home. It is odd to grasp that the place I grew up in is such a controversial topic. My experience of living in that community is the basis of my reverence for what I now photograph and contributes to why I am obsessed with highly charged issues.

The events of 9/11 completely challenged my perception of the place I lived in and of the military. I was in 10th grade and also too young to remember the effect The Gulf War had. My only memory is going to greet my dad when he returned home. My home was again an active site for conflict and loss, instead of a place in preparation for some event that could hypothetically never happen. Twentynine Palms is a United States Marine Corps training base with a climate similar to that of Afghanistan and Iraq; the base facilitated pre-deployment training during Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). The significance of this place will never leave me.

I was also raised in a different way than children with military parents typically are: one, my parents are both Marines (Once a Marine, Always a Marine); secondly, joining the military is usually a family tradition, but my sister and I learned the ideologies that are present in military culture without the objective of following in that tradition.

Why did you choose After Eisenhower as the title of your series?

My work is about the affect and effect the ‘military industrial complex’ has on culture. The term was popularized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower when he used it in his 1961 Presidential Farewell Address. I struggled for a while trying to find a title that represented enough elements in my project; when I reread Eisenhower’s speech these lines stuck out: “This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government.” This is basically what my project is about. Eisenhower made a mark during this specific moment because he foresaw what the implications of the growing military power would have on culture. ‘We’ are in the time after this warning and military power has continued to increase exponentially since.

Can you describe your approach to the work, and what did you want your images to communicate?

In 2009, I started photographing and engaging with what characterizes my hometown of Twentynine Palms. The community is directly engaged and economically supported by the military. I made lists of what defines a place by treating it as a typological study of military towns: tattoo shops, barber shop, churches, car dealerships, murals, flags, tailor shops, and also what ideals and socio-economic structures are present. I was interested in how proximity to a specific institution affects the culture of the surrounding community. This is not limited to military bases. I found a correlation in the likes of college towns and beach towns—they have a similar ‘feel.’ This is the basis of how I approach what I photograph: I defined my vernacular within known iconography and symbolism. The task is how to confront what is ‘known’ and also how do you photograph an ideology? My goal is to find the best examples and photograph them to the best of my ability. The context of the environment of these symbols is vital. I may place a flag in the center of an image; however, the way I choose to frame a scene is very intentional. I genuinely love the spaces I photograph, even if the symbolism is complicated.

Catholic churches and other Catholic religious signs come up in several of the After Eisenhower photographs. How do Catholicism and military ideals coexist in Middle America?

Religious iconography permeates American society. It is hard to dissociate military, religion, and America because of how linked they are.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on After Eisenhower?

Roy Stryker’s shooting scripts for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers from the 1930s and early 1940s when they surveyed Depression-era America. Contemporary examples are Larry Sultan’s ‘ideas for photographs’ and Alec Soth’s ‘hunting lists.’ Also, my guilty, but not so guilty pleasure, Internet comments responding to political articles on Facebook.

How do you hope viewers react to After Eisenhower, ideally?

We all come from our biases. The work is not neutral. I do not want to alienate opposing perceptions on the already charged subject matter intentionally. I want conversations to start about how I chose to frame a specific scene and how that confronts the viewer’s identity.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Deborah Willis, An-My Lê, Robert Adams, Gordon Parks, Alec Soth, Tim Hetherington, and my professors at CSULB and Columbia College Chicago.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

An-My Lê, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, Trevor Paglen, Zanele Muholi.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Perspective. Perception. Specificity.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2023

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2023