Religion, Violence and Mexico

We first featured the work of Hungarian photographer Adél Kolészar last July, in our first list ever of photographers to follow on Tumblr. Adél’s blog already showed some quite impressive, stark images of Mexico that could hardly go unnoticed.

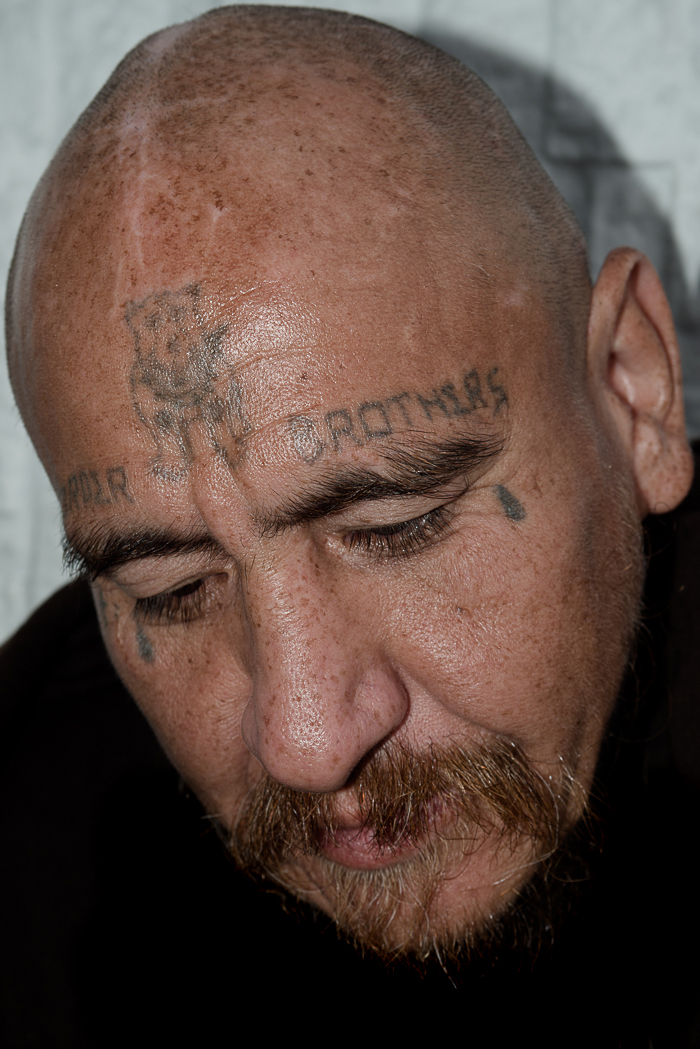

Eight months later, the photos Adél keeps sharing from Mexico continue to stagger us. There are guns, skulls, tattoos and an incredible gallery of faces, and shot in such a striking way that you just can’t stop looking. We had to get in touch with Adél, and have an interview with her.

So we did. In the interview, Adél shares some very interesting stories about the life of lower classes in Mexico, especially about the many alternative religions that are common in the country.

Hello Adél, thank you for this interview. You are originally Hungarian – where does your fascination with Mexico come from?

My fascination with Mexico started when I moved there. After graduating from the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in Budapest, I was already very tired of living in Hungary, and I was also concerned that there weren’t too many opportunities for photographers. I desperately wanted to move but couldn’t afford it on my own, so I took to looking for a grant.

I discovered that the Mexican government offers artist residencies for foreigners, which sounded just perfect for me, because I had always wanted to go to Latin America.

Your photographic style is quite a glaring, in-your-face one. Why do you feel the need to be so close?

I think my pictures reflect my personality: I am very straightforward in real life. I like to show my subjects in a very direct, harsh and quite shocking way. There are things people are scared to talk about – I want to throw them in their face and provoke deep thoughts, not just a shallow reflection on how cruel life is in some parts of the world.

How do you approach your subjects to take their pictures?

Mexican people are very kind and easily approachable, especially for foreigners.

The people in my pictures look like badasses, and many times they are. These are people from lower classes, some of them are criminals – men and women who belong to that part of society that we are taught to be afraid of, or at the very least avoid. This is especially true in Mexico, where social classes are so important.

I love taking pictures of these people: I don’t feel that different from them, I was born in a working-class family as well. I love their faces, their expressions, their stories. I approach them during public events, masses, churches, celebrations – occasions when you can connect with them easily, in which they participate to show off and so they possibly don’t mind being photographed. Some I have met through mutual friends. In some places you can also try taking pictures of strangers in the street, but you have to be careful: it is not a joke in Mexico, there are lines you shouldn’t cross.

The culture of violence in Mexico emerges in your photographs through recurring elements like scars, skulls, guns, bones, dollars and tattoos. The skeletal figure of Death carrying a scythe seems especially common – does it carry a particular value in Mexican culture?

Yes, it does. It is the main symbol of a very common local religion called Santa Muerte, the Holy Death. It is quite well-known and well-documented, but I had never heard about it before I arrived here. The roots of this cult are in the Catholic religion, but those who believe in it worship a skeleton lady, who will satisfy any of your requests if you pray enough.

Besides the prayers, you have to offer her some kind of gift – cigarettes, sweets, money, alcohol, etc., otherwise she will take away from you something of the same value of what you asked for. It is also very common among the devotees to get a tattoo of the Holy Death on their bodies.

I guess the first encounter with this cult is very striking for everyone, perhaps even frightening. You kind of realize there must be something really different going on in this country, if such a religion is so common and takes up such a significant part of people’s everyday life.

Aren’t violence and religion perceived as contradictory?

Not here. I think violence is so ordinary in Mexico that it was eventually incorporated in religion, too – that’s why so many alternative cults have originated here, and gained so many followers. This is the aspect i am focusing on right now, actually.

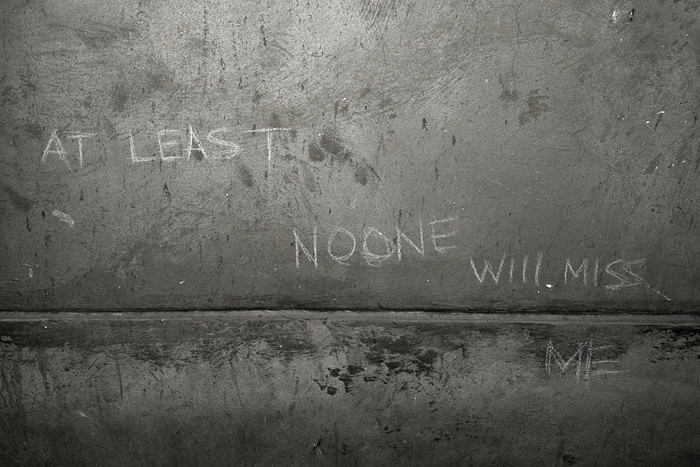

There’s a lot of pain in this country, especially in the poorest classes of the society. Almost half of the population lives in poverty, and they are the ones who take the hit of Mexico’s current problems. As a consequence, they often become either criminals or victims of crimes such as abuse, kidnapping, displacing, corruption, to mention the most common.

In this state of things, people have a strong need for religiosity. Alternative religions do not judge their believers, who are allowed to live a life of sin and pray for secular needs. Santa Muerte – the protector of outcasts, prostitutes, gays, criminals – is the most prominent example, but there are others.

The saint Jesus Malverde, for instance, was a sort of Robin Hood – he stole from the rich to give to the poor. Now he is the protector of narco-traffickers, poors and migrants. His cult is most popular in the state of Sinaloa, where, as the legend says, Malverde lived and eventually got killed by the police or a traitor. His body wasn’t buried, but left to rot in public as a demonstration.

Can you share the story of this picture?

This is related to the recent execution of 43 students by the hand of the police and narco forces in the state of Guerrero. I took this picture during one of the many marches in honor of the students that frequently took place for a while in Mexico City.

I visited the students’ hometown, Iguala, to assist another photographer, and that is when my perception of reality in Mexico radically changed. When I arrived, I saw many mass graves: as a foreigner, I used to think narco-traffickers were killing each other, but I realized the truth is more painful than that, and more nuanced. That experience made me feel that my pictures are a huge responsibility.

In your experience, what kind of country is Mexico today?

Well, it depends. Every state is different, both culturally and socially. Also, you will have very different experiences depending on which social class you belong to or interact with. Personally, Mexico has been very generous with me – foreigners can find joy in many things: beautiful places, kind people, affordable life, sense of freedom. I think it is an amazing place to be, but the deeper part of the local reality is way too cruel.

If you could change or improve one thing about the photography industry, what would it be?

The attitude. Share, work more together. Be less jealous.

Do you have any other passion besides photography?

Photography is my biggest for sure, and many of my other passions are combined with it. I love traveling, exploring new places, meeting new people and trying to figure out the society around me. Photography is also a way to access deeper layers of reality and put myself into situations that I would never be able to approach otherwise.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Information. Power. Fun.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in September 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in August 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2024