Lost and Found — Marijane Ceruti Wants to “Show the Grit it Takes to Carry on When Life Is Challenging”

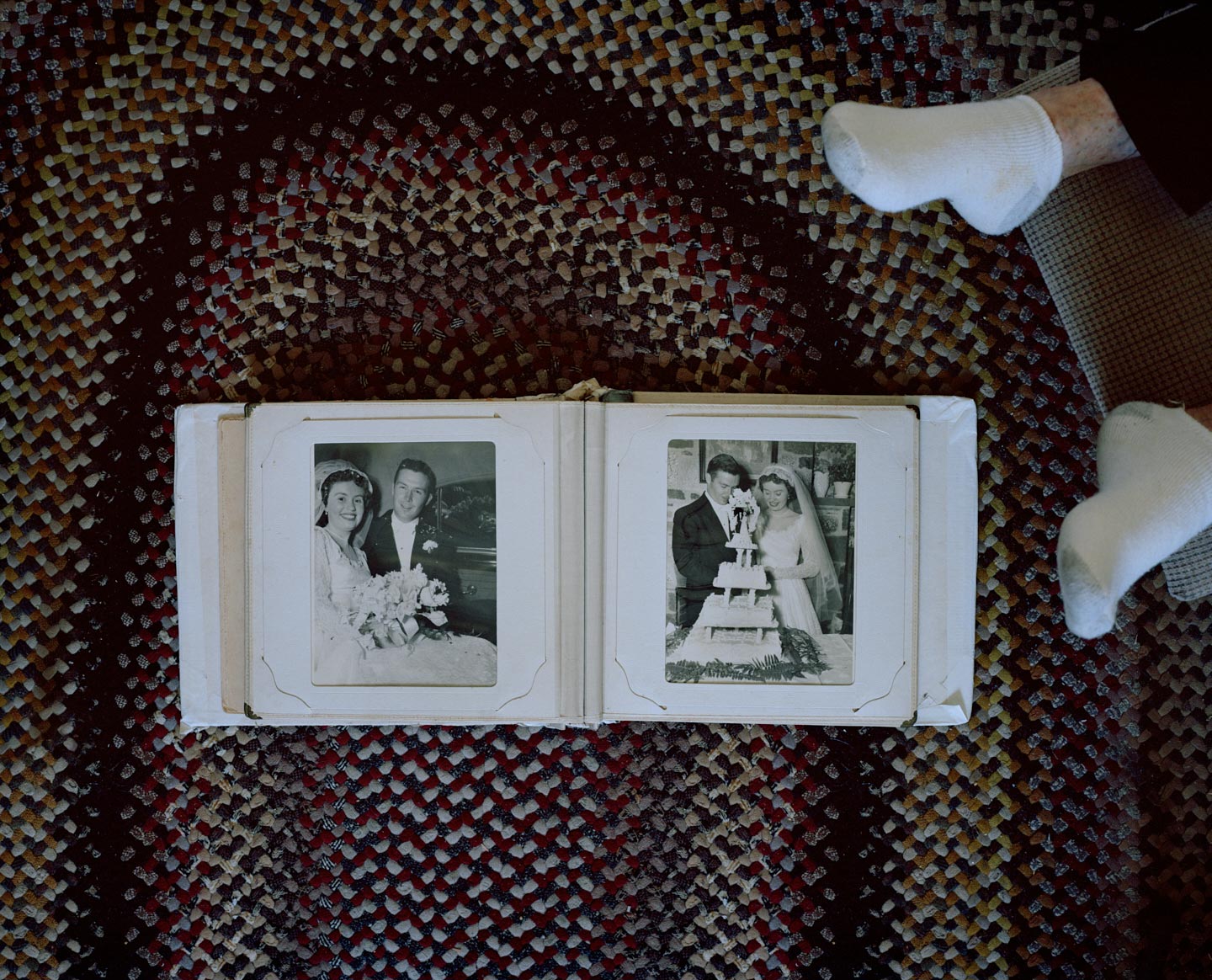

Lost and Found by 25 year-old American photographer Marijane Ceruti is a series of diaristic photographs that look at her personal experiences and the experiences of those around her. Rather than chronicling the difficult moments of the people in the photographs (such as her grandmother’s memory loss problems), the images of Lost and Found capture the weighty atmosphere that life can take on when things aren’t perfectly right.

Hello Marijane, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Thank you for featuring my work! My main interest as a photographer is to make work that is humble and original. I want to photograph my own experiences and experiences within my reach. I think that there is value to being an outsider, but I think it too often leads to objectification and judgement while disempowering the subject. I see a lot of work that fetishizes the other and a fictitious ideal of beauty; since I’m stubborn, I always try to create work that counteracts these trends that I find toxic. Empathy and bravery is huge when you want to make work that positively influences others.

Please introduce us to Lost and Found.

Lost and Found roughly began in 2014 just before my last semester of undergraduate school. I was living with my grandmother in her beach house, where I spent every summer as a child with my sister and two cousins. Back then, I had a lot of time to dedicate to photography and contemplation since I couldn’t find a job. I began photographing what was around me with a framework of nostalgia and memory in mind since my grandmother was in the beginning stages of memory loss.

After that summer, I continued to photograph my life and those around me. I would bring my camera with me everywhere. The Lost and Found images are a menagerie of different moments. I chose this title because in this period I’ve lost so much, but also gained a lot of life experience and wisdom. I also liked the dismissive and forgotten aspect that the title lends itself to since much of my work showcases outsiders and unpleasant experiences. Over the course of the three years the project took place, I lost one of my dogs to leukemia, had my first kiss and relationship at 23, and photographed a lot of pain. At its very core this series is about loss in its many forms and the grit that it takes to move on from it.

What inspired Lost and Found, and what was your main intent in creating this series?

My fine art work isn’t necessarily driven by an idea or a story. I like to create work that is instinctual and meaningful and then meditate on the experience and the moments within the images. I find the backstory to images endlessly fascinating. For example, the first photography book that I fell in love with was Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi. I loved the captions in the back of the book that told a short anecdote about the shooting process. I was so enamored by its design and the different levels that it operated on. I think good work functions and is accessible to anyone, but has layers to peel back for those that choose to learn more. When images are inaccessible or too shallow I am immediately turned off. I am so bored by the male gaze at the moment. I can appreciate pretty pictures, but stylized pictures of pretty people have nothing to them. With that being said, my main intent in creating this series was to collect images that were meaningful, complex and functioned on many levels.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to Lost and Found? What do you want your images to communicate?

I think the slow process of film photography really forced me into a relationship with each photo. They are expensive and time consuming to produce, and using a medium that takes your hard-earned money or hours of your time forces you to think about what images are worth working on and what you value as an artist.

My diaristic approach is the one that I am most comfortable in and satisfies my urges as a creator. If I see something or someone in a situation and I have an urge to photograph, it will bother me if I let that moment pass me by. I tend to ask “Can I take your picture?” a lot to those around me. Even if it feels uncomfortable or inappropriate, I can’t let it go or forgive myself if the moment passes me by.

I want my images to communicate the truth in pain and loss. I am not interested in appearing lofty or cool. I think that there is something beautiful about photographing people with whom you have a lot in common. It feels less like fetishizing and looking down on others. I think social media has changed our standards of happiness as a people. It glorifies the best parts of life by making everyone seem like they have more, are loving more or are doing more. I want my images to counteract that and connect people who feel that they don’t have that ‘more.’ I want to show the grit it takes to carry on when life is challenging.

What kind of an experience is photographing your own life and the people in it? Does it help you in any way?

I once heard about someone who would cup their hand and look at things through a tiny hole in their hand when the they became overstimulated by their environment. They would look at one thing at a time to better be able to digest the situation. This anecdote really stuck with me and I think that I relate to it a lot on some level. When something is really hard or I feel uncomfortable in a moment, to have my camera as a security blanket and to give me purpose is really comforting. I think this is why I am drawn to so many large format photographers (although I shoot medium format): it is such a slow and meditative process. The subject is fully aware that you are taking the picture and you can hide behind this big camera, but still look into their eyes. I shoot a lot of portraits on a tripod for this reason. You get a different reaction from your subject when they know that it’s not a disposable snapshot. It adds a level of seriousness and commitment to a good image on both ends. It’s refreshing to make something that you’ve invested in. Accessibility is a huge part of what I find attractive about shooting my life. I think that when you have to embed yourself in a situation you aren’t getting a full understanding of your environment where you can fully take responsibility for the statements you are declaring with each photograph.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Lost and Found?

I am constantly collecting screenshots, snapshots and quotes that inspire me. My camera roll, Tumblr, and Instagram are mostly pictures of things that inspire me. I’m inspired by a lot of different mediums other than photography that influence my work. I’m a big collector (borderline hoarder) when it comes to beautiful and meaningful things. I think that’s why I became attracted to photography in the first place. I come from a long line of people who are the same way. In my family, we have an ancestor’s wedding dress from just after the Civil War and “The Datebook,” which is a collection of photographs and objects from when my grandmother and grandfather started dating in 1948. I was definitely influenced by these objects and others like them growing up, and I think they definitely influenced Lost and Found.

How do you hope viewers react to Lost and Found, ideally?

I hope to bring more attention to female photographers and the female gaze. I am so interested in women that photograph other women and the generosity and connection that is shared. I hope that people look at my work and see imperfect people and strong emotions in each image. I think that vulnerability is a strength and it is so easy to hide behind sexuality and style, but to appear in a weakened state is so much harder. I hope they look at these images and see complex individuals and situations. I make my work for me and I think that once you start making work to please others is when it starts to lose its wildness, authenticity, and heart.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

My mother’s creative eye and good taste that has influenced me since I was a child, the large format photography class I took with Alison Hale, the research-orientated and supportive family I had at UConn, being a late bloomer in a lot of respects, my experiences in UConn’s Photo Club, my best friends supporting me and critiquing my work. I’ve been shaped by so many experiences and people I could go on and on… Also, when I first had an interest in photography as a teen I watched Annie Leibovitz’s documentary Life Through a Lens and Sally Mann’s What Remains and I was shocked at how much I related to the way that they viewed the world and photography. It solidified the gut feeling that I was on the right path. I am attracted to funny people and smart humor, so I am actively trying to add some element of humor into my photographs. I don’t think I’ve gotten there yet, but I’m working on it!

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Benjamin Vnuk, Susan Worsham, Sally Mann, and Alec Soth.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Humble. Prepared. Instinctual.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024