Virgin Lands — Mikael Hellström Captures the Loneliness of Stigmatized Ex-Prisoners

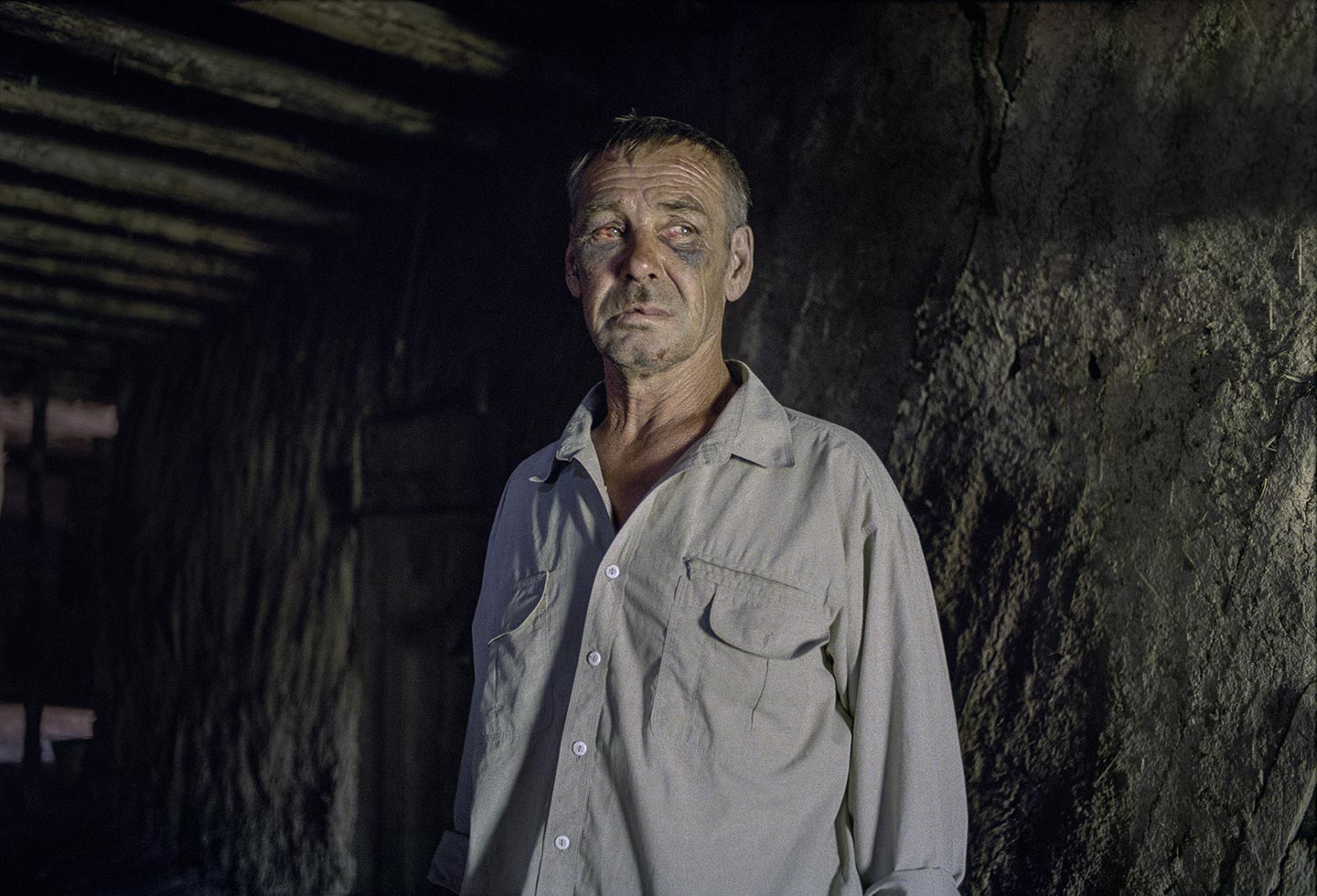

Can a prisoner really consider himself free when, once they get out of prison, they return to a place where no one wants them? The subjects of Virgin Lands, a beautiful series of environmental portraits shot by 37 year-old Swedish photographer Mikael Hellström, have been imprisoned for years—now that they’re free again, they and their close relatives are being isolated due to the stigmatization of other people.

Hello Mikael, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Thank you for inviting me. My main interests as a photographer have changed over time. When I started to become more serious about photography, I had a different approach. I was already deeply interested in the human condition, but I found it important to take an objective stance when photographing. Over time, my attention in documenting the stories of the people I met has not changed, in fact it’s still the most important thing for me; but today I’m more drawn to photographic work that shows a more personal point of view, and can tell something about the photographer as much as about the subject. I don’t think my approach needs to be less documentary, and my relationship with my subjects less sincere; but as far as aesthetics go I like to experiment away from the canons of traditional documentary photography. In that intersection, I find photography the most interesting.

Please introduce us to Virgin Lands: what is the work about at its core?

Virgin Lands is a series about former prisoners in northern Kazakhstan. The subjects of these photographs have been imprisoned in their homes, regardless of whether they were living alone or with their families. A few of the men have been incarcerated for up to twenty years.

Upon discovering their stories, I became curious about how being kept away from society for such a long time affects the human mind; how a person adapts to normal life once they become free again; and how the stigmatization of being an ex-prisoner harms an individual when trying to fit into a society where no one is willing to accept them. With this as a backdrop, I am trying to depict loneliness and longing, and to set an atmosphere in my images, by using the repetition of the subjects’ emotional expressions.

What inspired Virgin Lands, and what was your main intent in creating this series?

I first arrived in Kazakhstan in 2006 with an idea for a different project. About a month later, by chance I came in contact with a few people that had recently been released from prison after very long periods of time, in a small town in the Siberian part of Kazakhstan. Most of them were very introverted, and appeared to be feeling ashamed of just talking to others. I became interested in their past, and got to talking to one of these men. I started from there and after some time I got in touch with more ex-prisoners.

I felt that the stigma of imprisonment was probably going to follow these people and their families for the rest of their lives, so I wanted to create a voice for their loneliness. When many of them became free again, Kazakhstan had recently gained independence from the Soviet Union and was facing harsh economic conditions, which made returning to society an even greater challenge for the ex-prisoners. I became very curious about how you form an identity in these circumstances, and how it affects a child‘s identity to grow up with parents marked by this stigma.

How did you approach and gain the trust of the people you’ve met and photographed?

For the first month I didn’t take many pictures at all, but just spent time with them drinking coffee—sometimes vodka—and talking. This was also a chance for me to practice my Russian, which I studied at university. After a few months I had only shot a few rolls of film, and I didn’t think that the images were good enough. I felt accepted by the people I was photographing, but it took at least two more months to get them relatively relaxed in front of the camera. After all, these men had problems trusting people, considering their backgrounds.

A while later, I could tell some of them were happy to see me again if for some reason we hadn’t seen each other for a week or so. I remembered some even started to smile when I showed up, happy to have someone to talk to: almost everyone else wouldn’t even speak with them, which of course made it hard to create new relationships.

Can you make a few examples of the personal stories of the ex-prisoners, and what impressed you more strongly about them?

I can tell you the story of a man called Victor. Victor was incarcerated for about twenty years, convicted of manslaughter two times. He’s an alcoholic, and he beat two men to death during two different fights. The first time he was released from prison, Kazakhstan had recently become independent—many were unemployed and had problems with alcohol, since vodka was often cheaper than milk. So shortly after being released, unemployed and disillusioned, Victor started drinking again. He got into a fight, killed a man once again, and got sentenced to prison for a long time.

Last time I talked to Victor he was living with his dog and preparing for the long winter. He was still drinking, but now he was drinking alone in his house. He has a son and used to have a wife, but he doesn’t speak with either anymore. Victor is trying to live a normal life, but he knows he’s doomed to a life of loneliness. Stories like his have made a strong impact on me, and got me wondering how a human being, despite everything that has happened, can manage to keep on living in such circumstances.

In many of the Virgin Lands photographs there’s at least one subject whose face is blurred. What does that visual cue represent for you, and what did you want your images to capture more generally?

One simple explanation is that I was working with an analog medium format camera in low light conditions. I used the medium format because I wanted to be able to make large prints so the viewers could get a sense of almost entering the rooms. The disadvantage with this sort of camera was that I had to use long shutter speeds (about one second, and sometimes up to four). On the bright side, the light you capture with long exposures becomes very beautiful, almost dreamlike. Also, I find that the long exposures strengthened the relationship between me and my subjects in the images. For me that brings a specific quality to the pictures.

Concerning the blurred faces, at first they were purely an accident, but then in many photos I started to use it to my advantage, as if they were an expression. I didn’t tell my subjects to move their faces when I was photographing them; but sometimes I would take a picture when I saw an action or a subtle movement, just to capture that special expression. For me, those blurred faces suggest the temporal flow of an action or story, and in a way they challenge the formal and static composition of the pictures, which I think in part strengthens the atmosphere of the images. I was trying to create a repetition of these expressions to visualize a general mood of loneliness; I also wanted to convey a feeling of confinement through the walls and textiles around the subjects that recur in most images.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Virgin Lands?

I had plenty. In the evenings I was reading books that were somehow related to the projects, such as One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and Crime and Punishment by Fëdor Dostoevskij. I was also reading history books like Anne Applebaum’s Gulag, since the area I was working in, earlier known as “Virgin Lands”, had an important role when the “Gulag” labor camps were created; some of the ex-prisoners I met are also descendants of former Gulag prisoners.

During my first trip to Kazakhstan, I lived in the same town for five months, and these books helped me when I was alone in my apartment, giving me something to do before going to sleep. They also made me reflect and provided inspiration for the images I would make in the following days.

How do you hope viewers will react to Virgin Lands?

My aim with this work is not to create some objective truth about the lives of these people, but rather to offer an insight into a state of mind, which is very much created by my own experiences, and my interpretation of loneliness and longing. That is also what I hope viewers will do: form emotions and some sort of understanding with the help of their own personal experiences.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

It’s hard to pin down precise influences—it changes with time. I look at other photographers’ works as much as I can, and I try to look at as many genres of photography as possible, as I believe that gives you a broader idea of the medium when developing your own style. I’m also inspired by film directors like Steve McQueen, Bela Tarr and Andrei Tarkovsky, among others; and painters such as Dick Bengtsson and Lena Cronqvist.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

When I started this series I was very much inspired by Lise Sarfati’s work Acta Est, which I still look at from time to time. I also have to mention Philip-Lorca diCorcia, who has been an influence when it comes to mixing documentary with a very personal and aesthetic approach. I also admire Alec Soth’s work a lot.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Subjectivity. Patience. Time.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024