To the North Pole with a Camera and a Group of Polish Scientists

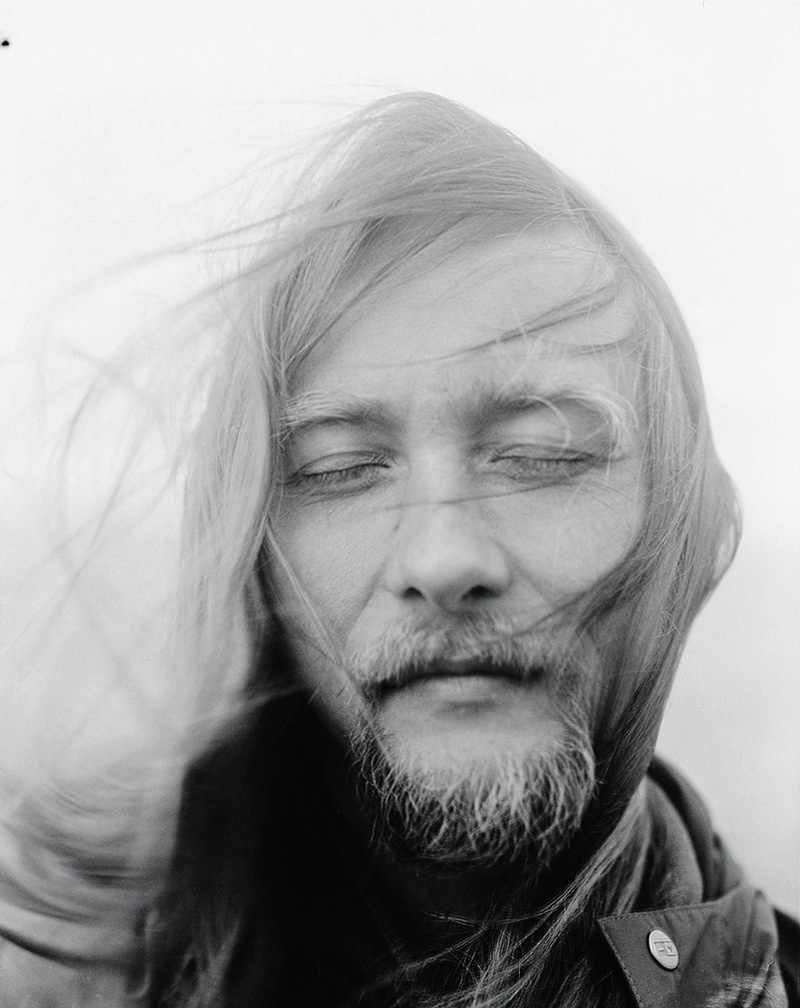

Anka Sielska is a 37 year-old Polish photographer born and based in the city of Katowice. A few years ago, Anka followed a group of Polish scientists in an expedition to the North Pole, with the intent of using photography to make a connection between art and science.

Hello Anka, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Hi, thank you for having me. I’m interested in various subjects, really. Recently, I have been working on a long-term project about the connections between people and plants in collaboration with the members of the Culture of Image Foundation and the students of the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice, where I’m a teacher.

I’m also fascinated with vernacular photography, such as family albums, and the stories behind the photos. Lately, I have finished working on Art of Photography – Art of Survival, a project which uses photography in the treatment of trauma: together with therapist Helena Zakliczyńska, we conducted a series of workshops for 10 women, which resulted in a final exhibition. There’s a lot going on! Life is dynamic, and so are my interests.

Why did you decide to embark on a journey to the North Pole along a team of scientists?

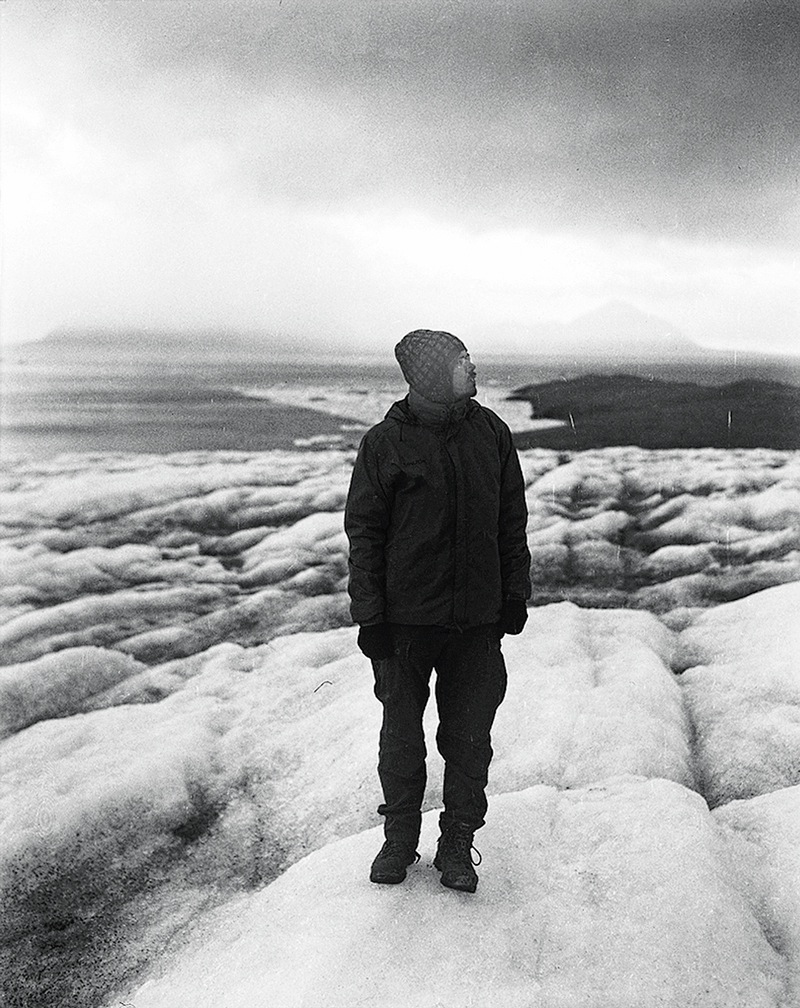

For several reasons. First, I was simply curious and wanted to travel. In 2009, I watched Werner Herzog’s film Encounters at the End of the World, and I became fascinated by those who, looking for their place in the world, end up all the way down to the South Pole. One of the movie’s characters, Stefan Pashov, a philosopher working as a digger-driver in the polar station, called these people “professional dreamers”.

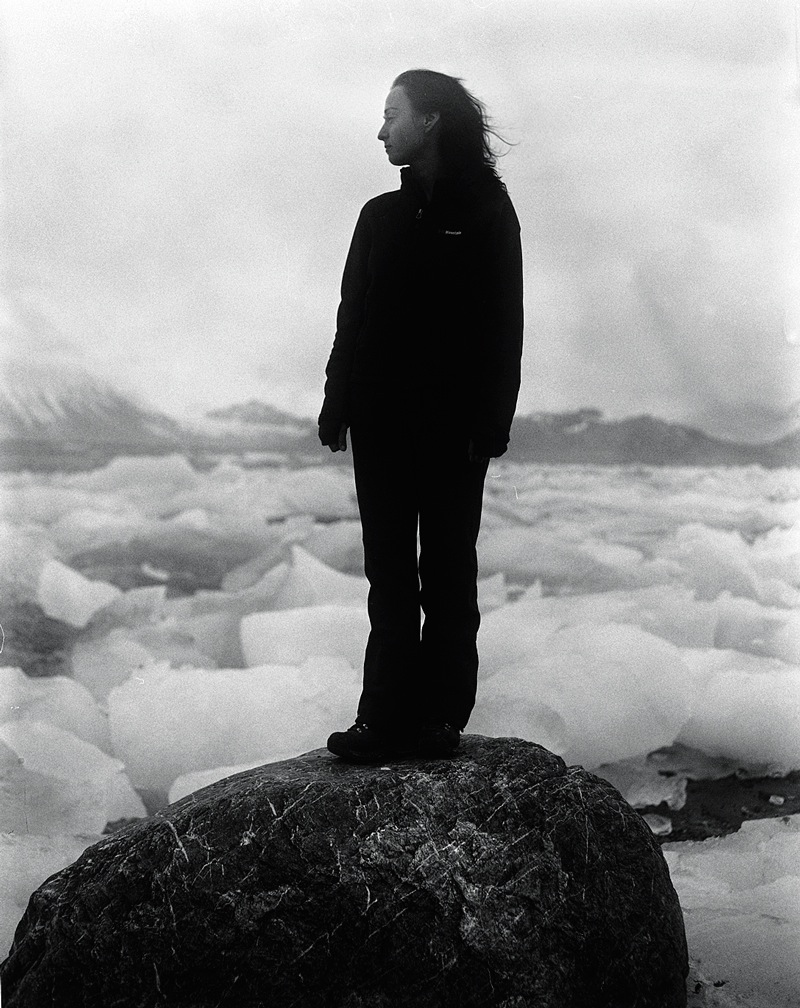

Beside the people, I was drawn to the emptiness of the landscape, which I assumed had to intensify the feeling of isolation. Moreover, I have always been afraid of cold and open spaces, and taking photos helps me tame my fears. In January 2012, I was offered an opportunity to go to the Polish Polar Station Hornsund at the North Pole. My initial idea was to only take a set of portraits of the scientists there. Photographs would fall within the photo aesthetics of the first half of the 20th century, when a camera accompanied the pioneer expeditions to the poles.

In your statement you say that “the project attempts to analyze the mutual relations between art and science“. Can you elaborate?

As I said before, I have been interested in relations between photography and science for some time now. I try, in cooperation with scientists, to research into a subject visually, through photography. I used to wonder whether such cooperation, between artists and scientists, was even possible.

When I travelled to the Polish Polar Station, at first I was frustrated with the lack of understanding on the scientists’ side. My presence raised many questions, sometimes doubts even, initially. I realized our professions run parallel, but they never, or hardly ever, meet at all, and my book proves that. It also made me aware that our jobs are similar in being non-surreal. In both cases, there’s a particular work to do. We respected one another.

What is the meaning of your work’s title, Salix Polaris?

Aboard the Polish Academy of Sciences ship, I met Dr. Piotr Owczarek, who was going to Bear Island to collect rhizomes of the polar willow, the Salix Polaris. This plant is studied by dendrochronologists, who can determine its age based on the number of growth rings. They also use microscopes to read its past from healed wounds in the figure of the wood. It was the first time I’d thought about the title for my photographic cycle.

In a way, the Salix Polaris became a symbol of my journey to the Pole. The polar willow is a small shrub only a few centimeters high. Its form resembles the human nervous or circulatory system. It is strong, wind and frost resistant, and its fresh sprouts can also develop under the snow. To me, the polar willow has become a metaphor of the explorers’ determination.

Please share some insight into the decisions made for Salix Polaris, both in terms of imagery and aesthetics.

As I was getting ready for my journey, I studied a lot of contemporary projects, both photos and films, about the North Pole. They were mainly color, beautiful photographs. However, I was particularly endeared by black-and-white photos of early polar expeditions. To me, those photos are special and authentic at the same time. They made me think about the photographers, and how they worked in very difficult conditions. It must have been a challenge.

So I decided to take photos with a Graflex camera, on 4 x 5 in. frames, and to make them black-and-white photos. The book also contains three color photos of samples collected on Spitsbergen: water, deposit and the Salix Polaris. The photos are accompanied by short scientific descriptions.

Tell us a bit about the Salix Polaris book.

Initially, I had no intention of making a book – all I wanted was to go to the Pole and photograph. As I said, I was only supposed to take portraits of the scientists. It turned out, however, that life on the base is quite monotonous. Everybody works. Every day, weather permitting, the scientists go into the field. Every day, the climatologist collects samples of meteoric water; the geologist checks the Earth’s magnetism, reading data from the non-magnetic house; the seismic movements get analyzed. It’s hard to make appointments to photograph anybody.

When I was there, several research programs of various disciplines were underway. All the photos were taken in only a few days. Unfortunately, due to difficult weather conditions, my backpack with my Graflex camera and tripod couldn’t reach the station near the Werenskiold Glacier. This was a failure to me. Michał Łuczak, who was editing the book, decided that this failure, or obstacle, could became the inspiration for making the book. A little book about a great failure, so to speak. But really, it is first and foremost a book about a struggle against nature and yourself.

Mention the skill that you think is most critical in the education of a photographer.

Being curious and open to the world.

We think not enough people even realize that they can enjoy photography just like they enjoy films or music, and not necessarily as photographers but simply as viewers. What would you tell these people to pique their interest in photography?

From my experiences working with young people interested in arts and design,

I don’t really see this problem. The most important photo competitions have been keeping up with the times by including new categories like multimedia and photobooks.

But here you are probably asking about people who are not connected with artistic circles. Still, I think the situation is not bad. In Poland, we have several photo festivals that are quite good, and I have a feeling there are more and more visitors every year. At the gallery of contemporary art in my town, it’s photography exhibitions that attract the most visitors.

If you could change or improve one thing about the photography industry, what would it be?

I don’t feel connected with any photo industry. I teach photography, I co-create the foundation for the development and promotion of photography. The major problem we tackle as a foundation is obtaining sufficient funds to meet our statutory objectives.

Think of the last time you saw something and you couldn’t resist taking a picture – what did you see?

Working on the project about plants, I have recently started observing my 5 years old daughter in contact with nature, usually while walking in the forest.

Do you have any other passion besides photography?

Yes, exchanging experiences with young people, the students of the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice. It is fascinating.

Choose a photograph from Salix Polaris and share with us something we can’t see in the picture.

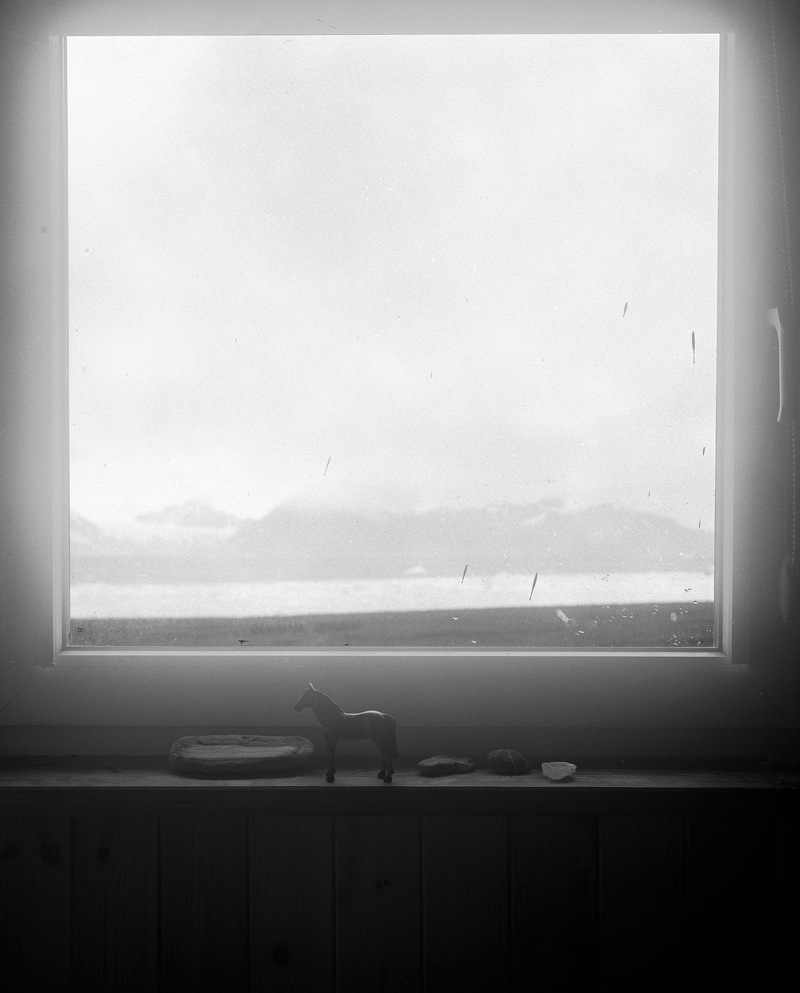

I like this photo a lot. It shows a knot on the frame of my pine wood bed in the room of the Polish Polar Station. This image was the first thing I could see every morning. It became a symbol of my mindset at the beginning of my stay there. Anxiety, fear, longing for home. Then I came to tame it.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Pang. Silence. Afterimage.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in July 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025