Water — Mustafah Abdulaziz’s Fifteen Year Long Look at the World’s Finest Resource

30 year-old American photographer Mustafah Abdulaziz discusses Water, a stunning, long-term documentary project with a global scope about how we use water, and the threats posed by its scarcity. Mustafah started working on this project in 2011, and intends to continue at least until 2026.

Water will be on view at London’s The Scoop for Water Stories, Mustafah’s first solo show in the UK (opens next 22 March – see here for details).

Hello Mustafah, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Exploration, inward and outward.

Please introduce us to your long-term project Water.

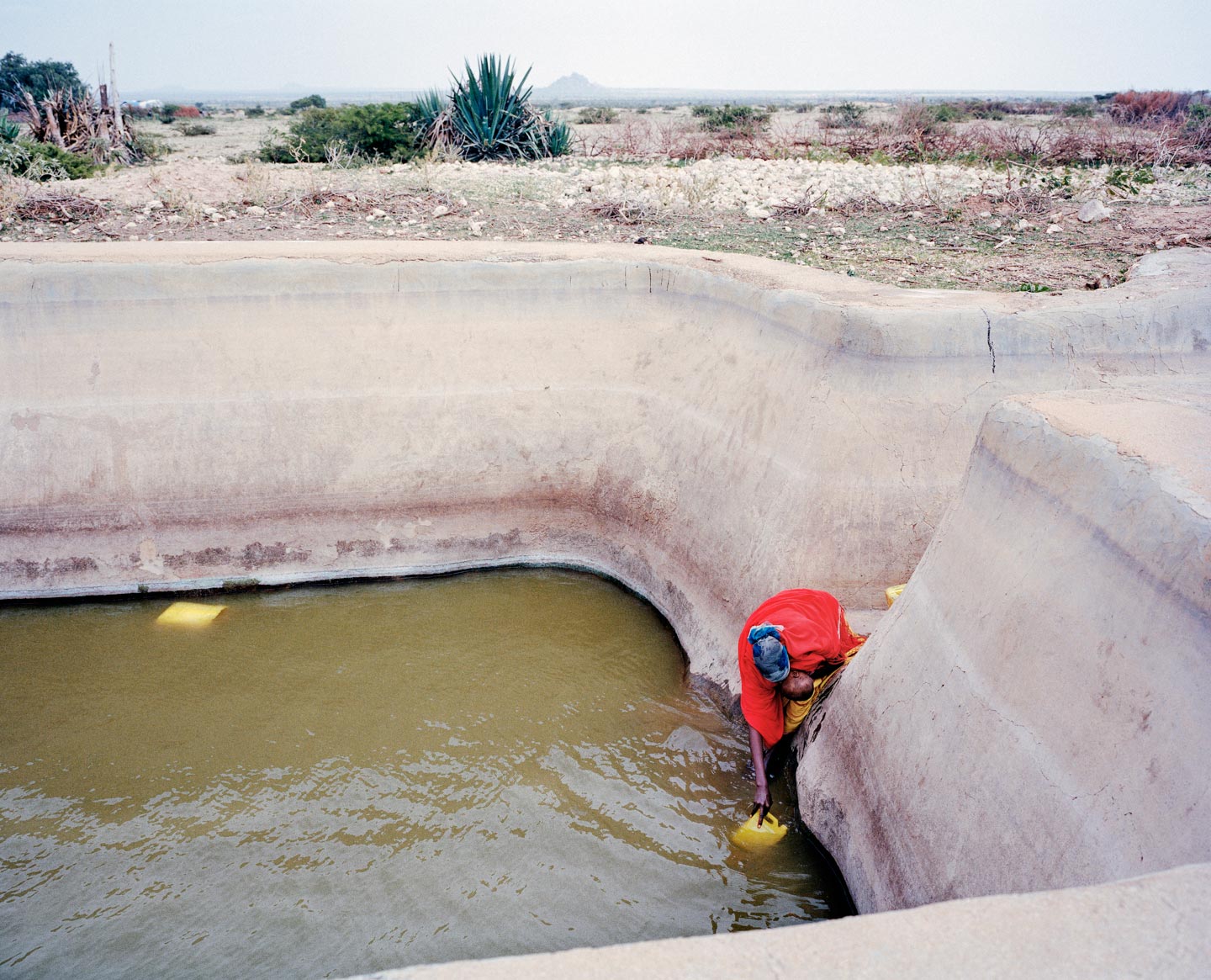

Water is a fifteen-year photographic documentation of human beings and their interaction with this one critical resource.

When did you start working on Water, and what compelled you to make this project?

The project began in 2011 with the understanding that water and humanity were moving towards a crisis. We live in a time when 650 million people have no access to safe, improved drinking water; when our rivers, basins and lakes are being affected by decades of industry; when rising sea levels are placing Pacific islanders in the cross-hairs of becoming the first climate refugees. The complexity of our relationship with water, as a species, reflects our greater behavior towards our environment, which we’re only recently beginning to understand has a huge impact on our planet.

As I researched further into issues of water, I began to see the possibility of using photography not as a way to inform the viewer but as a way to give perspective on this overwhelmingly large subject. There was – even at the early stages of planning this fifteen-year work – a very logical argument to be made for intelligent discourse on how humanity and water were interacting.

For Water, you’ve been traveling around the world. Based on what do you choose which countries to visit, what countries have you visited so far, and how long do you usually stay in each?

The work is thematically based, not geographically. Although there are countries I’ve determined to be critical to include for their severity or relevancy, there are also places in which I see the potential to create smaller pieces of the project.

The work began in Sierra Leone in West Africa during the 2012 outbreak of cholera, then progressed to a journey down the Ganges River in India, followed by a look at access to safe water in Somalia, Ethiopia, Pakistan and Nigeria. In continuation of my desire to travel all of the world’s major rivers as a minor theme within the Water project, I’ve been working on the Yangtze River in China and the Pantanal river basin in Brazil. The world can seem awfully large at times. I see each place as a chapter and seek to build piece-by-piece, slowly and with great care.

Tell us more about your most recent work you’ve been doing in China.

China was a two-month trip split into a month of experiencing the Yangtze River firsthand with my friend Niko as a journey of exploration and feeling. The grant from VSCO I gained gave me an unprecedented level of freedom and support, and allowed me to make the type of work that I had touched upon with my travels along the Ganges, but fulfilled in my time on the Yangtze.

This first month was followed by a second month of focused reportage on key issues of river health and management through my partnership with World Wildlife Fund. When I began Water I committed to the idea that both the logistics and methodology of photographing this project would, in many regards, reflect some of the same fluid qualities of the subject I’m documenting. Each chapter is done with a similar but slightly different creative process, with different partners and different goals. The chapters all build upon each other. I find that working in this way keeps me engaged and invested in pushing the work in new directions.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to Water, photographically speaking? What kind of images are you creating?

The photographs in the work so far are observations of behavior, or more specifically, instances where humans are at the crux of their own needs for existence and realities that are outside their control. Technically, the whole project is 6×7 medium format film and some of the newer work is 4×5. Across the next eleven years I’ll introduce a few more cinema-leaning perspectives in medium format as I begin to go underwater. The process is slow, requires a little more exactitude and I find it brings me closest to what I imagine is important for a commentary on water: a patient and humanist look at ourselves and our resource.

You have set an approximate end date for this project at about 11 years from now. How did you establish this deadline, and why do you feel your Water project requires so many years to complete?

The timeline is as much for myself as it is for the logistics of planning, funding, photographing and disseminating the work. Water is a topic that demands not only patience but nuance. I feel fifteen-years is a commitment that allows for growth, for new partnerships to take root and for the work itself to fail and succeed in its own time. It is very possible I’ll continue on after the fifteen years.

You mentioned you’re making Water with the help of the Artist Initiative grant by VSCO. How was your collaboration with the mobile app born, and do you ever use mobile photography or the VSCO films for Water?

Each partnership in Water facilitates a different aspect of the work. When I began discussing with VSCO the idea of doing a part of the project with the Artist Initiative, I found that we clicked on something very important but often times overlooked. They understood that the way to create honest and powerful photography was to support the vision, passion and the freedom of the photographer.

All the work in Water is film. To travel a river takes time. To find the right outlet for the work, whether through public installation or exhibition, takes even more time and resources. This was something VSCO understood and supported, which allowed me to fully focus on making what I needed to make.

Do you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on Water?

That varies, depending on what day you’re asking, and what country I’m working on. An early influence for my motivation to create the project can be traced back to the book Martin Eden by Jack London, and the documentary Encounters at the End of the World by Werner Herzog. When I was on the Ganges I was fascinated by Andreas Gursky’s work from the late 1980s and early 1990s. During my research for my time in East Africa, I had opened the Pandora’s box that is NASA’s open source archives and photo accounts of satellite imagery. For California, I was interested in how people behave during a drought rather than the drought itself, and one of my favorite authors on human behavior is Kurt Vonnegut. I don’t often like to look at photography before or during my trips. After, when the negatives are yet to be scanned do I feel like seeing other photography.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Richard Avedon, Garry Winogrand and RFK Funeral Train, 1968 by Paul Fusco.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

Luc Delahaye, Pieter Hugo, Mikhael Subotsky, Alec Soth and Sylvia Plachy.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in June 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024