FotoFirst — Jon Horvath Looks at the American West Myth From the Small Town of Bliss

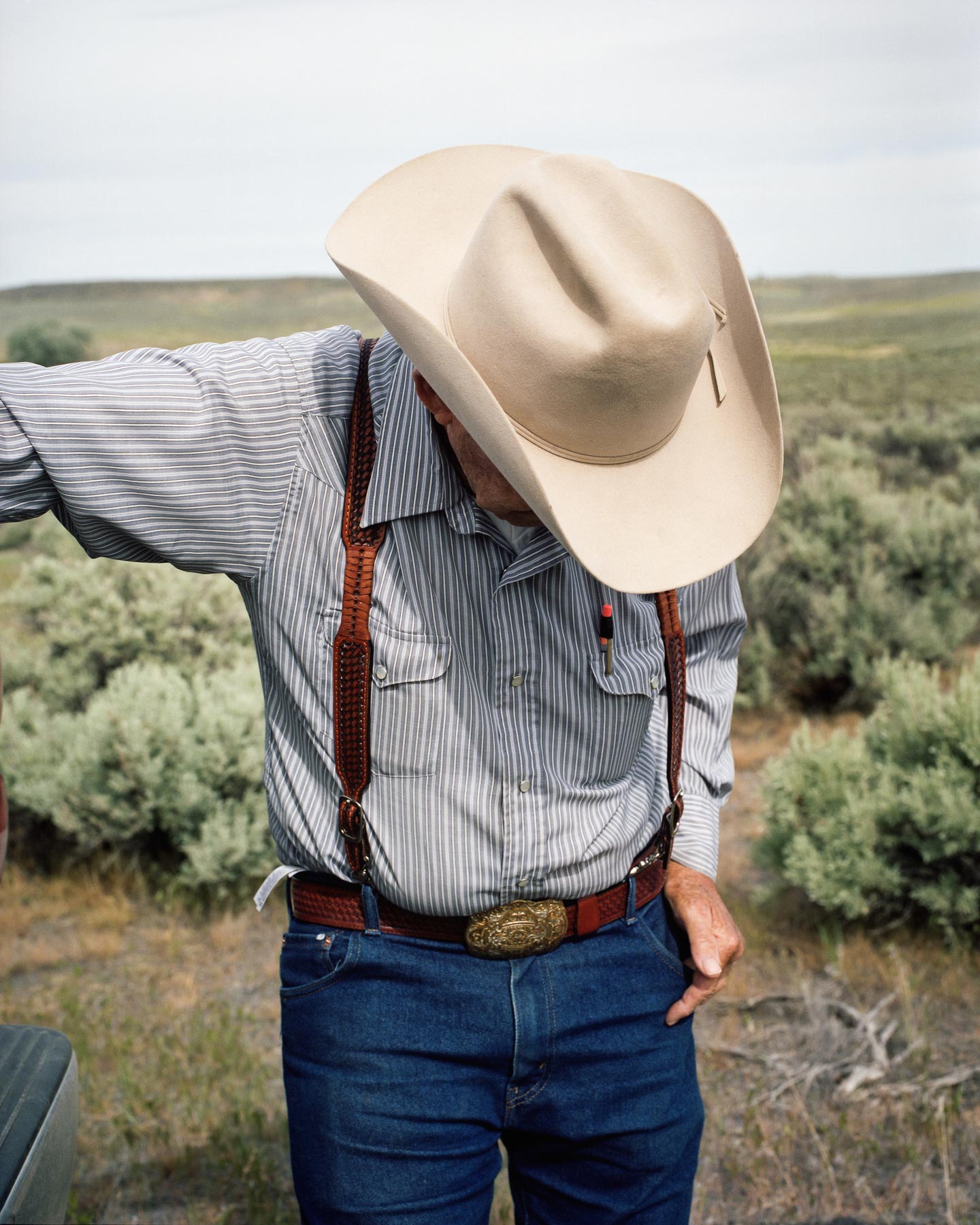

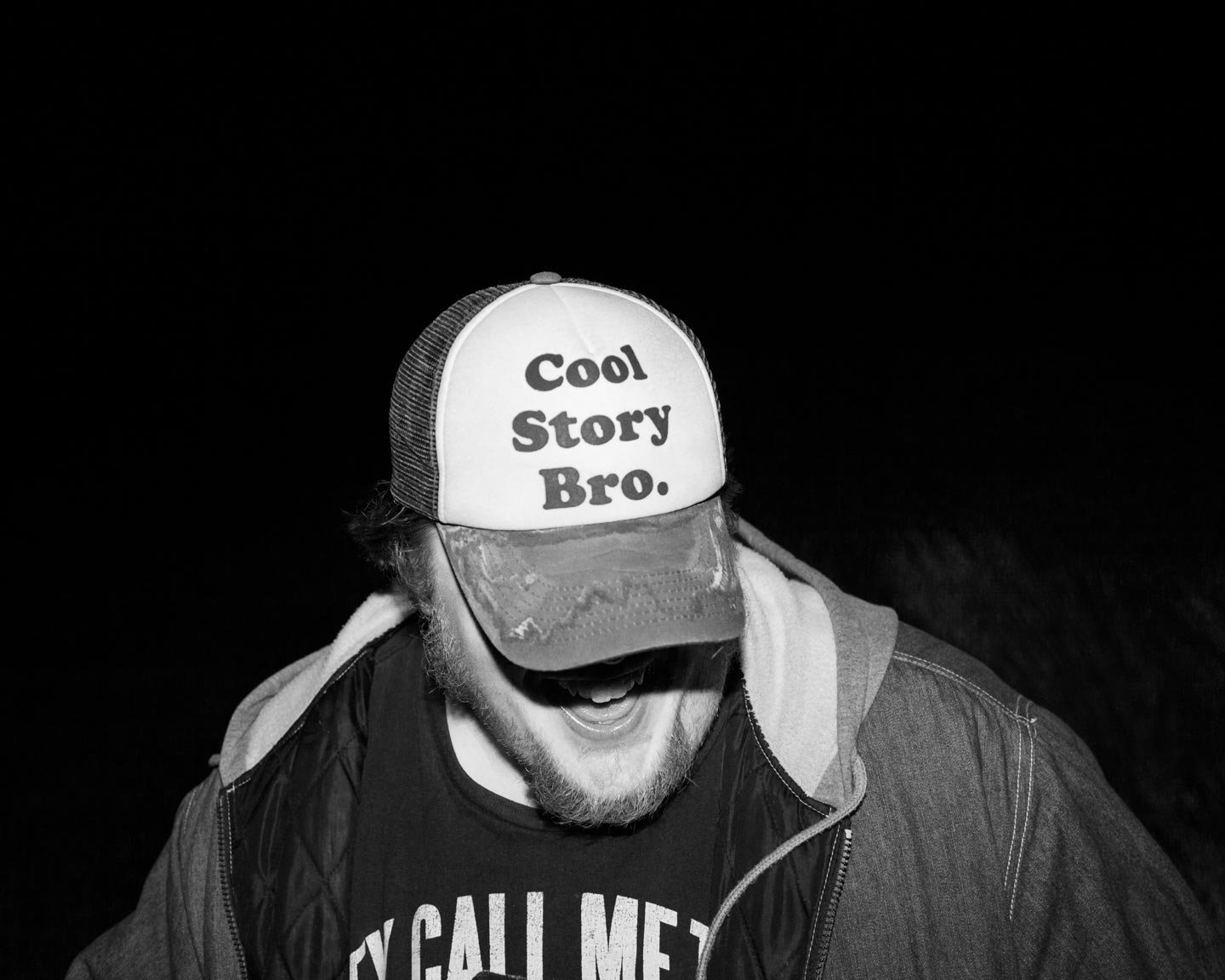

37 year-old American photographer Jon Horvath presents This Is Bliss, an ongoing body of work that compares the myth of the glorious American West with the reality of Bliss, a small town in Idaho with a population of 300 people.

This Is Bliss is currently on view at the Haggerty Museum of Art in Milwaukee, Wisconsin until next 31 July (see here for more info).

Hello Jon, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

Hi, thank you for taking interest in my work and sharing it with your readers. My interests as a photographer are frequently evolving, but there are a couple of primary characteristics to my practice. First, I often work within systems or a set of constraints when producing works; I like handing my process over to chance and am welcoming of unexpected outcomes, whether that involves the materials I’m working with or some performed gesture I’m attempting to make. At the same time, I find that I’m often interested in the narrative capabilities of art, and not just photography. Some of my recent exhibitions have involved combining photography with video, sculptural objects, performance, and written works in an attempt to create a narrative experience across numerous forms. I’m interested in concepts of place and travel, language, absurdism, literature and pop culture, romantic gestures, and the inherent futility that comes with striving towards some sort of impossible ideal.

Your new project This Is Bliss focuses on the rural town of Bliss, in the American West. What’s the story of this town?

Almost everything I know of Bliss, Idaho has come through my interactions with town residents. Geographically, it’s located on the Snake River and intersects the Oregon Trail. Bliss is a small town, currently with a population just over 300 residents, and is comprised of a few local establishments including a school, a church, a couple of motels, bars, gas stations, and diners. It served as a support system for road travelers for many years and then was affected by the construction of Interstate 84, which ultimately directed traffic past the town instead of through it. But, it’s a town with rich history, a harsh and beautiful landscape, and people that have welcomed me and put great effort into making sure my days were filled with things to see and do. One of the great aspects of this project, for me, is that I’ve been able to work with some of the residents in order to bring many of the project’s pieces to life, so there is an underlying collaborative spirit to many parts of the bigger This is Bliss whole.

Why did you decide to make a project about Bliss? What was your main intent in creating this body of work?

I happened across Bliss by chance in the summer of 2013. I was traveling home from Portland and in the middle of the Idaho desert I saw a highway sign that read “Bliss” with an arrow pointing the way. That was enough to spark my curiosity, so I decided to exit and take a look around. I quickly met a man watering a corn patch in his yard and we got to talking. He told me about the town’s current state, as well as the broader history of the area, which was part of a larger American story, but often with dark and undesirable aspects that sat just below the surface. By the time I left that day, I knew I had to come back and make something in response to the encounter I had.

Can you share some insight into your creative process for This Is Bliss?

My original desires were to visit Bliss and make work thinking about some of the mythology associated with happiness, as well as mythologies of the American West. I didn’t really know what to expect regarding my interaction with the residents, so I arrived on the first day with a list of things I could attempt in the event I was going to be a solitary maker. That’s where pieces like 10 Blissful Sunsets, a multi-channel video of the sun setting in ten different locations in town, and Serenity Lane, a video of a night drive on a circular dirt path in the desert, came from.

Fortunately, though, I met numerous people within the first couple days that came filled with suggestions for people I should meet and sites I should visit. So, the limits of the project expanded considerably and led to something much larger than I had ever anticipated. I’ve now made four trips to Bliss and in the end, there are photographs that serve as portraits of the people and their surroundings, video, small performance works, collaborations with town residents, and even a short story I’m working on that is inspired by encounters I had.

How would you describe the pictures you made for the project? What kind of images did you aim for?

As somebody from Milwaukee, who had previously spent relatively little time of substance in the West, I was fully aware that my firsthand understanding of that region was probably influenced by myths, stereotypes, and cliches more than anything else. I went in with the attitude that myths often form for a reason, but are typically a significant departure from the full story. They are constructions that might be based on real people and real events, but time allows those stories to become romanticised, embellished, and ultimately imprecise. I think that influenced how I approached the photographic portion of the This Is Bliss project. I wanted to include allusions to those archetypal myths of the West, but be balanced with imagery that includes a real place with real people. That said, I don’t think that I can ever fully escape the presence of those myths, so at the end of the day, I know the pictures depict the Bliss of my personal construction and that I’m not sharing an historian’s version of the town.

How do you hope viewers react to This Is Bliss?

The project is still in-progress, so this is a difficult question for me to answer. Of course, I hope that viewers will become invested enough in each of the project’s component parts to begin to assemble the larger narrative at hand. Ultimately, I hope that via the pictures, viewers will consider how myth and local lore come to define the story of a place.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind while working on This Is Bliss?

I did quite a bit of preliminary research before my first return visit to Bliss. The broader project references the greater region surrounding Bliss and includes some allusions to the Oregon Trail, Evel Knievel’s failed Snake River Canyon jump and Ansel Adams’ photographs in the west. But as I mentioned, most of my understanding of the place came through the people themselves. That’s where I learned about Holden Bowler, a former Bliss resident who is widely considered to be the inspirational namesake for J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield character. Catcher in the Rye has had a huge influence on me and to find the supposed “real Holden Caulfield” in the middle of the Idaho desert in a town of 300 was certainly a surprise; especially considering the name of the town is Bliss and Holden Caulfield has never been considered to be the best representation of a happy individual. It’s discoveries such as that one that have encouraged me to continue my visits. Every time I go back some new part of the story emerges.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

The quick list: American literature, stand-up comedy, melancholy music, and people who aren’t afraid to do things that other people might not understand.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

This list is always changing, but people I regularly revisit would include Christian Patterson, Rinko Kawauchi, Jason Lazarus, Alec Soth, Uta Barth, John Divola, Birthe Piontek, Onorato and Krebs, Matthew Gamber, William Lamson, and about a million more.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Curious. Unstable. Surprising.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2024