FotoFirst — Inside Trona, a Ghost Mining Town Dissolving in the Mojave Desert

Scottish photographer Ewan Telford presents his previously unpublished series Rock Salt. The work revolves around Trona, a Californian mining town founded in 1914 that has been progressively abandoned over time, and has today a population of a little over 1,000 people.

Hello Ewan, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

They vary from project to project, but generally I’m interested in photography’s capacity to express a certain consciousness beyond the descriptiveness of the images. I am not very interested in individual photographs, but more in sequences that may work both in the service of narrative or on an abstract level, accumulatively. In the case of Rock Salt, it was largely a documentarian approach, albeit a very measured one, which is just the way the project manifested itself over time really.

Please introduce us to the story of Trona, the mining town we see in your Rock Salt series.

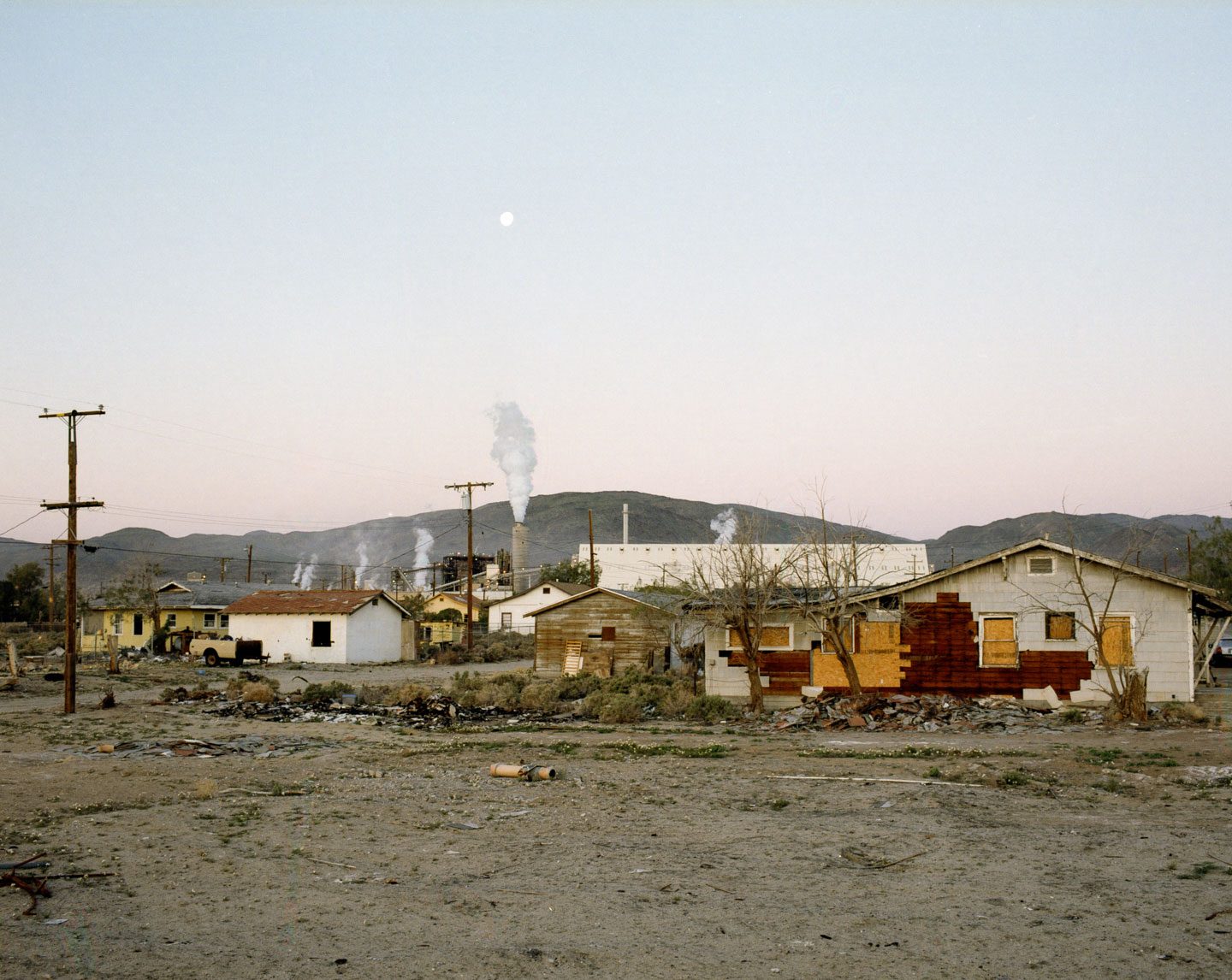

Trona is a mining town in the Mojave Desert near Death Valley, California. An urban experiment, it was established in 1914 by American Trona Corp to house a workforce extracting borax and soda ash from Searles Dry Lake. ATC wholly owned and operated the town, which grew into a community of 7,000; it built housing and schools, grocery shops, dance halls, cinemas, a lido and a golf course. ATC payed its employees in part in its own currency (company scrip) redeemable solely at company owned facilities.

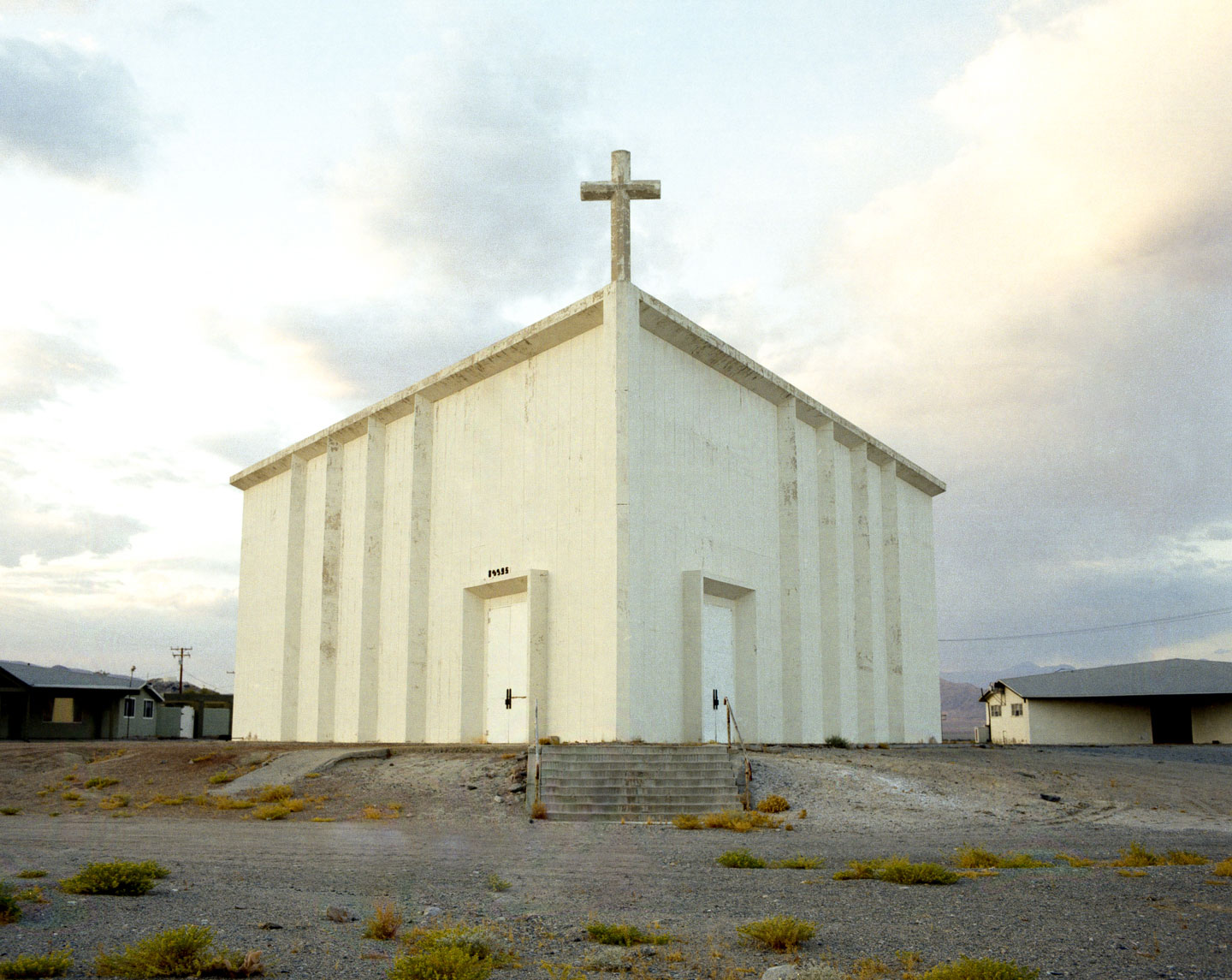

Labour disputes and strikes in 1970 and 1981 led to civil unrest, arson and bombings. By the mid-80s, over 75% of the workforce had been fired or made redundant, whilst remaining non-union became a condition of employment. Decline followed; houses, now employee-owned, were abandoned, shops and facilities shuttered. Whilst the processing plants still produce two million tons of industrial minerals a year, Trona’s population today is 1,100 and falling.

How did you come to know of Trona, and what impressed you the most about it that you decided to make it the subject of your latest project?

I worked on a film there about ten years ago and always planned to return to photograph it. I was struck by the landscape and the dramatic image of this little town dominated by steaming processing plants. Beyond that I was taken by the story of a town and community brought into being in an extreme, inhospitable place by an as it were God-like business enterprise only to be subsequently abandoned along with its workforce, which only existed in service to the corporation. I saw this as an extraordinary breach of faith and as an example of corporate misconduct. It’s a powerful index of the world we live in. There are lots of stories like this, all over the world, of course.

Can you talk a bit about your approach to the work? What were you most interested in capturing in your photographs?

My approach involved a mixture of planned shots and chance I suppose, as for most photographers. Certain images I knew I wanted and would wait for the light and so forth; the others, especially the portraits, just came from wandering about and meeting people or exploring the place. I wanted to capture a sense of life in Trona, what it is like to live there, but without being too prescriptive. I wanted to capture its “beingness” if you like, over offering an interpretation of the history.

The series includes the portraits of several locals. What do the people of Trona think of their hometown and the life they lead in it?

Most of the people I met there have grown up in Trona and have affection for it, naturally, and it’s a wonderful community. Other people are transient or find themselves stuck there for one reason or another but can’t leave, usually due to financial straits. There is a palpable resentment of ‘the company’, especially amongst the mid to older generations, many of whom once worked at the plants. Some will talk of damaged health as a result of their proximity to, or having worked in, the plants; others don’t believe it has caused any health issues.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind for Rock Salt?

I see this project and the approach I took to it as part of a tradition in American photography that one might see going back to the likes of Walker Evans. But the main inspiration was the startling physical reality of the town and its context. I just responded to that. I didn’t go in with the thought that I had a certain theme I wanted to cover, or even the story of the town per se.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Cinema, painting, other photographers. My father: he introduced me to photography and gave me Eric de Maré’s book Photography when I was fifteen.

Who are some of your favorite contemporary photographers?

There are so many. To name a few: Vanessa Winship, Geert Goiris, Alexander Gronsky, Tim Richmond, Matthieu Gafsou, Martin Kollar and Richard Edson.

Choose your #threewordsforphotography.

Time. Witness. Ideal.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2024