The Aral Sea Used To Be Here

How do you make a lake vanish? We’re not talking about a glass of water here; we’re talking about a lake. And not any lake, but the once fourth biggest lake of the world: the Aral Sea.

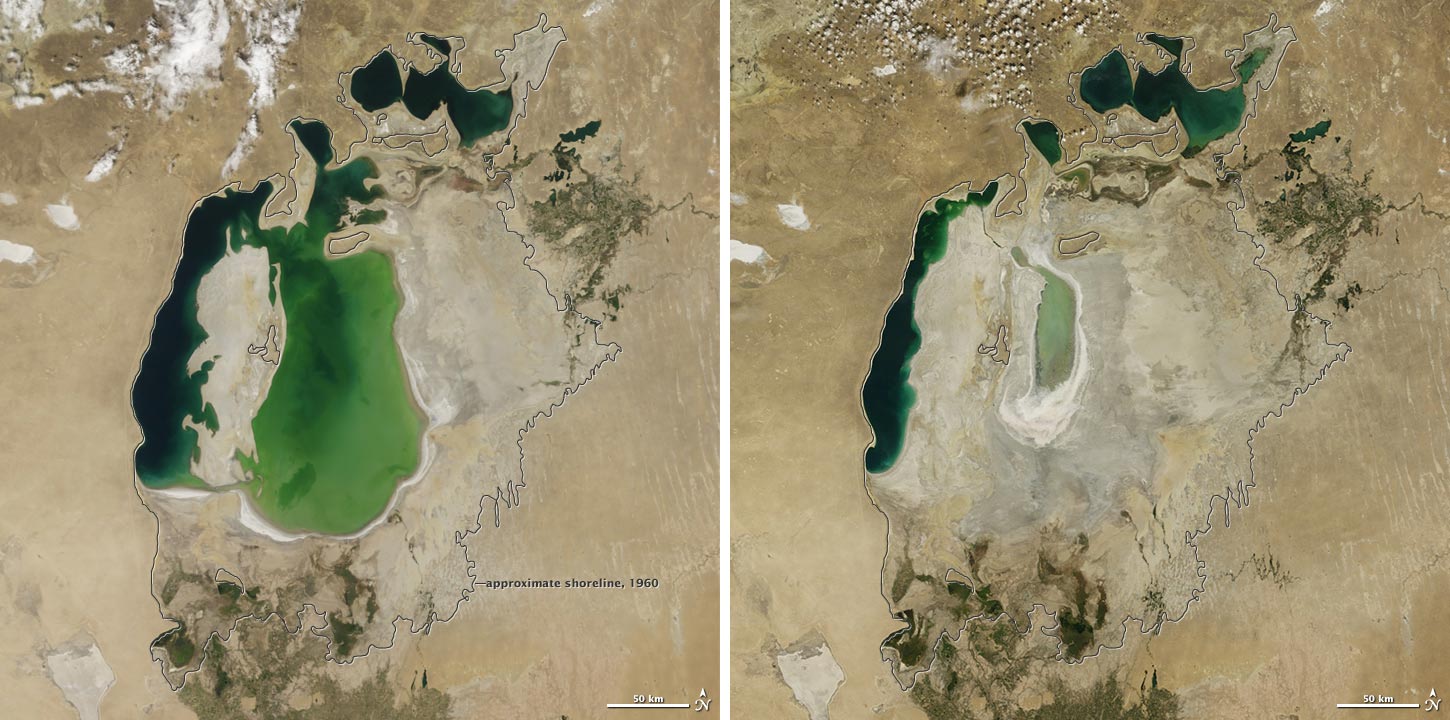

The Aral Sea used to have an extension of 68,000 square kilometers—that’s bigger than Sri Lanka, and quite as big as Georgia. But today, the lake shrunk down to something between 5 and 10% of its original area. With the lake gone, the economy of the communities living on its shores, which had fishing at its center, was greatly affected. And because when it rains it pours, the vanishing of the lake also produced an increase in toxicity of the environment as well as climate alterations.

In his series Desiccation, Welsh photographer Paul Dixon documented the life of one of these communities. In his statement and captions, he also offers deeper insights into what problems the vanishing of the Aral Sea is causing in the area, so be sure to read those as well.

The Aral Sea, partly situated in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic of Uzbekistan, was once the fourth world’s largest lake and belonged to the former Soviet Union. In 1958 the Soviet Union diverted the two rivers that fed the Aral to grow cotton and rice in the desert to export. Consequently, the sea has evaporated leaving behind it a toxic environment.

Today with the sea further than 120 miles (190 km) from its previous shoreline, the entire ecosystem verges on collapse. The Amudarya and the Syrdariya rivers now fail to reach the Aral, running dry before they are able to replenish the Sea which has evaporated into three heavily polluted and saline lakes. Unable to support fish species, the shrinking of the Aral has lead to the collapse of an economy once reliant on its fruits.

Economic problems are now such that doctors, some having not received pay for more than seven months, are having to work as taxi-drivers in order to provide for their families. The shrinking of the sea also affects the climate, winters are dryer and colder, temperatures regularly plummet to -25°C, while summer temperatures are hotter and often rise to 50°C. In these conditions, it is impossible to farm on all but the smallest of scales.

Meanwhile, the continued cultivation and intensive irrigation of cotton, on which through export the Uzbekistan government is now dependant, has resulted in the salinization of the land and the contamination of the water supplies by salt and agricultural chemicals.

The former fish basket of Central Asia has become the waste basket of the region, as a large proportion of the salts and agricultural chemicals upstream are deposited in the canals, on which all life depends. This water, the region lifeblood, is by international standards, unfit for human consumption.

As desiccation of the area continues, the salts and chemicals amass on the dry seabed and are blown back into the faces of the population by the area’s strong winds. Which, in conjunction with the consumption of contaminated water and food, has resulted in a plurality of health problems and one of the most chronically sick places on earth.

Anaemia, lung and kidney disease, high blood pressure, numerous cancers and tuberculosis are rife. Given the chain of casual events, the Aral Sea crisis is not just about water; air quality, nutrition, climate, the economy and the health care system are all plunged into crisis.

We’d like to thank Paul Dixon for his pictures. Visit his website to see more of his work.

Keep looking...

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in May 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in April 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in March 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in February 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in January 2025

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in December 2024

FotoCal — Photography Awards, Grants and Open Calls Closing in November 2024